Inside Man

Movies are what they always were, but more so. The way I keep describing the current situation is that everything you watch plays like an airplane movie now. When I say this, I’m assuming that you’ll know what I’m talking about, and that you, like me, are rendered especially emotionally susceptible to the effects of films viewed while 31,000 feet above the Earth. I don’t know if it’s the air in the pressurized cabin, or the customary sleep-deprivation that results of never learning your lesson and staying out late the night before an early-morning flight, or the usual melancholy attached to comings and goings, or some combination of all three that makes me respond with disproportionate feeling to moments that I might not otherwise mark as exceptional, and with a spluttering breakdown to those that I would be moved by under any circumstance. I’m thinking of a particular transatlantic round trip on which, due to a combination of inclination and lack of viable options, I watched The Bridges of Madison County (1995) going both ways, in a middle seat on the return, certainly discomfiting my neighbors with wrenching, ragged sobs at Clint standing in the pitiless pouring rain with the saddest plastered-down forelock in cinema.

Bridges plays a key role in Ulrich Köhler’s In My Room (2018), most of which takes place in the aftermath of the unexplained disappearance of seemingly everyone on earth aside from Armin (Hans Löw), a pushing-40 failson who is born again in self-reliant isolation, seen at one point vaping in solitude while watching Eastwood’s movie. Köhler’s film struck me as a little too droll for my taste when I saw it, but this scene, along with Charlton Heston firing up Woodstock (1970) in an abandoned movie theater in The Omega Man (1971), has been much on my mind of late, since for myself, as for many people, moviegoing for the first time in our lives has been stripped of even the possibility of containing a communal aspect.

Already the films watched during quarantine are starting to form some distinct category, even though there may be little-to-no curatorial logic behind their selection. In their contextual categorization, too, they’re like airplane films, or post-breakup movies, or, for cinephiles of a certain age, things watched out of the corner of the eye while manning the register at a video store—I estimate that I must have “seen” the 1979 Linda Blair vehicle Roller Boogie several dozen times in the latter fashion, but have I ever really seen it? For some time now I have been dipping in and out of Yuri Slezkine’s doorstop tome The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution, a story of the Soviet Union as told through the lives of the residents of the eponymous Moscow building constructed as a home for prominent Bolsheviks, and one item that recurs is the importance of the reading-circle book lists worked through during the hard days of Tsarist repression, even years after the fact. “Most fathers closely monitored their children’s reading,” writes Slezkine, “which included the same books they had read themselves in prison and exile (and continued to reread), in a particular order.”

The circumstances of our current isolation are enormously different from those of the exiles, not least because, rather than passing around a few treasured, dog-eared volumes, we are yet untouched by scarcity, most of us in the wireless world sealed up with the bounty made accessible by 21st-century technology at hand, our access to media theoretically unbounded by the limits of our physical holdings—at least so long as the Wi-Fi holds. I have seen it suggested that COVID-19 will make cinephiles of everyone, as though it was only long commutes that were keeping most people away from that Mikio Naruse deep dive. In point of fact everyone, self-defined cinephiles included, still seems to be mainlining Netflix true-crime series—which is fine, of course. Whatever gets you through the night, it’s all right.

The Bridges of Madison County (Courtesy of Amblin/Malpaso/Kobal/Shutterstock)

Aside from the appeal of the shiny and new for as long as it lasts, there have been certain spikes in thematic viewing, of the sort that made Steven Soderbergh’s 2011 Contagion, not exactly a hotly discussed item three months ago, the sudden movie du jour. One of the last films that I watched in the company of friends, as some were already starting to self-quarantine and many remained unaware of or unconcerned with the severity of the situation, was the long Japanese cut of Kinji Fukasaku’s 1980 epic Virus, in which the appearance of a mysterious illness called “the Italian flu” devastates humanity, leaving only a handful of survivors at bases in uncontaminated Antarctica to rebuild. The most expensive movie ever made in Japan at time of its release, with a hodgepodge international cast that includes Glenn Ford, Sonny Chiba, and Chuck Connors manfully attempting an English accent, it’s far from a sterling piece of work, but it does have its moments of beauty, pathos, and absurdity, sometimes all at once. In one particularly jaw-dropping scene, the crew at a Japanese station make contact with a 5-year-old named Toby outside of Santa Fe who’s using his dead father’s ham radio, and have to listen in mute horror as the boy, hopelessly lonesome, blows his brains out with daddy’s gun.

Oh, for the carefree days of communal laughter at the apocalypse! Like that of most people living alone, my socializing is now almost entirely confined to the virtual realm. Theatrical programming cancelled, we fall back on home video holdings, streaming services, and, to my mind most vital, the economy of swapping and sharing files like samizdat. A regular weekly moviegoing gathering that I’ve long participated in relocated to a cluster of Google Hangouts. We recently had occasion to gather together while apart and watch Herman Yau’s virusploitation classic Ebola Syndrome (1996), a no-redeeming-social-value Hong Kong picture bearing the disreputable Category III designation, a rating introduced in the late 1980s that strictly barred viewers under 18. (The forbidden fruit is rather more tart than that held out of reach by the American NC-17, as HK films of the period were as a whole juicier.) It features a puffy, ponytailed Anthony Wong as a one-man plague, a Sweeney Todd–type restaurateur creating an epidemic through surreptitiously served human flesh and wantonly spilled seed. Where Virus ends on a note of renewal, The Ebola Syndrome offers a compelling argument for the elimination of the human race.

There is a comfort in cinema as tawdry as the headlines themselves, though for some, the prospect of these vast sudden expanses of time to be filled conjures up the desire to scramble for the opuses, the monolithic masterpieces too long put off when subject to the demands of a normal schedule and social life—the Prousts and the Middlemarchs. In terms of movie-viewing, this means taking up arms to set out and slay the massive monsters of cinema, and as the extent of the social-distancing measures being proposed became clear, Film Twitter was abuzz with suggestions for epic-runtime films that could be readily found online. And for some, evidently, the “Time Enough at Last” opportunity has been productive—I have friends who’ve gradually been working their way together through Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah (1985), with breaks to discuss via Zoom.

For my money, though, these durationally daunting items are the sort of films least suited to home viewing, and I don’t think I’m alone in feeling this way. For good or ill, in the age of day-and-date releases—now entering undiscovered country as major studios scramble to hawk online the ill-starred new releases whose runs were interrupted by the shutdown of cinemas—a quiet consensus seems to concur that “cinematic” is a synonym for “large.” This holds true for the turgid tentpoles that dominate the multiplex while mid-budget pictures disappear, but also among rarified specialty releases; when Aleksei German’s Hard to Be a God (2013) and the rerelease of Sergei Bondarchuk’s War and Peace (1968) pull boffo B.O. on the specialty circuit, is not perhaps part of the appeal their sprawl, the feeling that these are big movies, meant to be seen on the big screen?

Contagion (Courtesy of Warner Bros/Kobal/Shutterstock)

Me, I need the sensory deprivation of the cinema’s black box for cinema’s endurance tests to take; it’s not quite the same when you can pad into the kitchen and fix a sandwich in the middle of the Sátántangó (1994) cat-torture scene. For large-commitment viewing projects, then, I lean toward film series, and making my way through Criterion’s Godzilla: The Showa Era Films, 1954-1975 has made instructive viewing. A particularly pertinent exchange in Ishiro Honda’s 1964 Mothra vs. Godzilla leapt out on re-watching, in which a security guard is warned of Godzilla’s approach, but refuses to budge because of the boss’s threat of dismissal if he leaves his post. “Are you crazy? We’re talking about Godzilla,” he’s told. “I know, but being fired scares me just as much,” he replies. The Godzilla films deal explicitly with act-of-God disaster and crisis (mis)management, from the first iteration to Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi’s 2016 Shin Godzilla, which moves between awesome imagination of disaster and a comedy of bureaucratic errors, as a slow-moving gerontocracy struggles to rouse itself to confront a threat to the very existence of Japan. (Somewhat poignantly, an American envoy, played by Satomi Ishihari, is presented as representative of a culture that values youthful dynamism and expertise over seniority.)

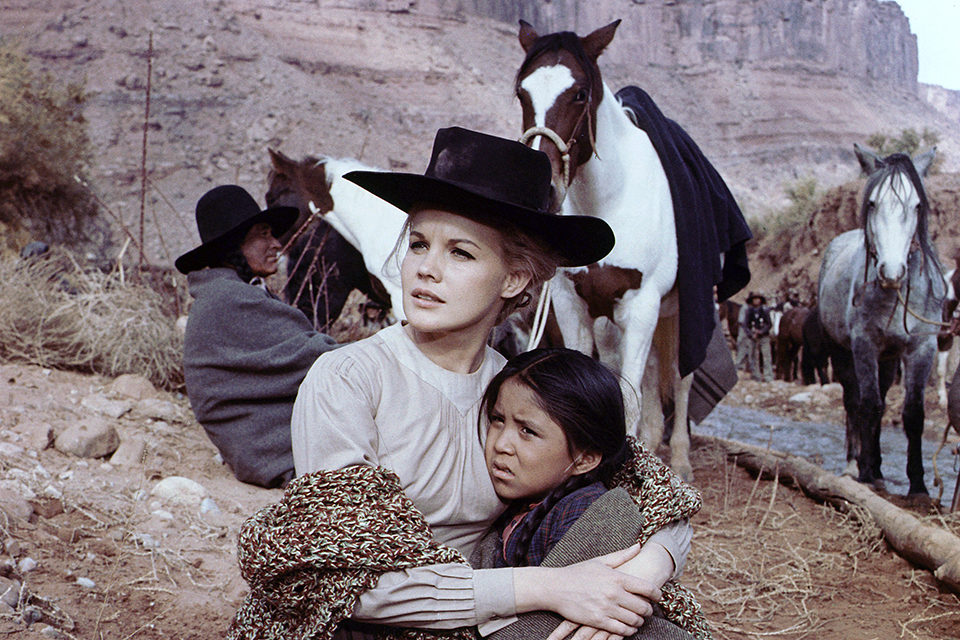

Certain films may seem particularly “relevant” to the present moment, but none seem untouched by it—and the disappearance of touch in daily life, of intimacy of the everyday sort and otherwise, is an absence dearly felt. In John Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn (1964), a little thing like Quaker schoolteacher Carroll Baker minding an injured Native American girl while continuing to give her her lessons, encouraging the girl to spell the word “Good” while holding a cup of water to her lips, suddenly becomes enormously moving: the mindful regard, the everyday act of succor, the very concept of G-O-O-D at a moment when the need for it is so evident.

There is this sort of tenderness, and another kind, too, as pent-up libidinal energy finds some unusual outlets. When you’re suddenly wholly living vicariously through films, they can become an incredibly tactile experience. Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple (1985) pivots on a kind of emotional dam-burst moment, when Celie (Whoopi Goldberg), treated abysmally through her adult life by a high-handed, abusive husband indifferent to her pleasure, finally discovers self-esteem and physical commiseration at the hands of his mistress, Shug (Margaret Avery). The lovemaking itself is elided, but the camera closely tracks the moment when fluttery anticipation gives way to mutual consent: tentative, giggly, exploratory preludes ending with a committed kiss, and the decisive placement of each woman’s hand on the person of the other, the beginning of a caress.

Reader, I swooned. Every conceivable varietal of pornography remains on tap in the internet-capable home, but deprived of company, the qualities of “charisma” and “chemistry” take on a new value. Watching Jean-Claude Tramont’s All Night Long (1981), an enormously amiable and enjoyable light comedy revolving around the shy romance between married-but-not-to-each-other couple Gene Hackman and Barbra Streisand, I found myself thinking for the first time in my 39 years: “Am I in love with Barbra Streisand?”

Cheyenne Autumn (Courtesy of Warner Bros/Kobal/Shutterstock)

Yearning for movie stars, a disgraceful hallmark of moony adolescence, returned—and several friends I’ve spoken to have found in the experience something akin to a trip back to the OXY Pad years. At the risk of generalizing—and there are exceptions!—cinephile origin stories tend not to have an early passion for the great outdoors at their heart. There is among our ranks a perhaps higher-than-usual percentage of Vitamin D–deficient latchkey kids well-accustomed to solitude from formative years spent watching movies in the dark: at the cinema, glued to the television, downloading furiously, ticking off “must-see” boxes. If we as a group have a single identifiable talent, it must be the ability to sit still indoors. If, per Blaise Pascal, “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone,” we must be of great service to the world. I spent a goodly portion of the summer following my parents’ divorce sleeping on the fold-out sofa in the living room of what was suddenly only my mother’s house, watching Three Stooges films on UHF every single day, and I account it one of the best summers of my life. (I should add that I had a bedroom; I just wanted to sleep in the glow of the television, and was taking advantage of lingering feelings of parental guilt to get my way.)

For many inveterate moviegoers, the first years of really intent, studious film-watching correspond to the adolescent and teenage years, the combination of aesthetic indoctrination and hormones a heady one. At the threshold of adulthood, movies can provide a vantage—if very often a deceptive one—on what lies ahead, a means through which to fantasize, and to rehearse for real life. They can offer a preamble, an anticipation.

And then, hopefully, you start that life, and that relationship, just as hopefully, changes, and the life that you start to lead and the art that you carry with you through that life wend together and inform one another in all sorts of different and subtle ways, and the films in your life come to matter less in some respects, and more in others. And then suddenly life is suspended, as it was some weeks ago, and there’s no outdoors anymore. I don’t suppose that I’ve been so alone with movies as I am now since I was in my early teens visiting my mother in Alexandria, Virginia, where I had little-to-no friend group, and so would hole up nightly with a pile of rentals from Video Vault, a particularly “cult”-oriented video store run out of a multi-story townhouse in Old Town by psychologist and onetime Reagan administration appointee Jim McCabe and his wife Jane, which I then regarded as the most wonderful place in the entire world, and still do.

There’s an unsettling intimacy that comes with this enforced isolation. Buffers between private and professional spaces break down, and via various chat apps, I am for the first time seeing the inside of the apartments of people I’ve known socially for 10 or more years. (This may be strange anywhere else in America, but it isn’t in New York.) Without access to accustomed social outlets, one is a bit more forthcoming than one—and by this I mean “me”—might otherwise tend to be. But I simply don’t know of any other way to talk about the strangeness of being suddenly reduced to living through films again.

Shin Godzilla (Courtesy of Cine Bazar Toho Company/Kobal/Shutterstock)

That watching movies is both a solitary and social activity is a paradox that’s been belabored to the point of cliché, but the importance of its social aspect becomes doubly clear in its near-total absence. Having, after a fashion, made a living out of writing and talking about movies, I suppose I’ve stayed more loyal than most to that guiding memory of adolescent infatuation with cinema. But being forcibly recalled to that first flush of affection has also acted as a reminder that solitary communion doesn’t represent some pure state of commiseration with the movies, and that much of what I owe to films is in the access they eventually offered into a larger fellowship of interest, a way of being in the world—however imperfect—and a sense of beloved community, at home and abroad.

To see movies again in a state of almost umbilical dependence is to see them anew, and while there is value to this confidential reintroduction, I find myself in its wake desperately yearning to see one instead with my dipshit pals in a theater, then to jaw afterward in the lobby and grab a drink or six around the corner at the foulest possible bar. But while my Blu-rays are safe and my AVIs and MP4s are in scrupulous order, there is no guarantee that the cinemas and the foul bars will still remain when the current pandemic abates.

In the 1970 book Decline and Fall, Otto Friedrich’s firsthand account of the slow scuppering of The Saturday Evening Post, he writes something I’ve reflected upon more than once: “If all things in our system were as interchangeable as twopenny nails, this system might work better than it does, but the laws of profit make no allowances for time and tradition.” I can scarcely think of a moment when the threat posed by the laws of profit to moviegoing tradition has been greater, and behind anything else in this quarantine has been one thought: while we’re trapped alone with the cinema, we must already be working together for it.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.