In the American Grain

The kind of love I have for the film is not as a filmmaker adoring a child, it’s as a part of the literature of America.”—Nicholas Ray on The Lusty Men

One of the great magical moments in recent cinema, one that has periodically come back to haunt me, consists of nothing more or less than two brothers, living in the middle of nowhere in the colorless America of the 1980s, coming together in a fluorescent-lit wrestling ring for a sparring match. The action of this scene from Bennett Miller’s Foxcatcher and its details are remarkable: the warm indulgence of the one brother and the granite-jawed determination of the other, the familiarity, the quiet slapping sound of flesh on flesh, the indissoluble bond between physical intimacy and the purest violence. But what gives this scene its particular charge is the suddenness of it, the way that all this bonded closeness and aggression comes at us all at once. Above all, it’s a matter of rhythm.

In 2011, the great American poet Peter Gizzi gave an interview to Levi Rubeck in BOMB. He was placing his own poetry within the context of 19th-century American literature and the relatively belated appreciation of some of its greatest practitioners: the rediscovery of Moby Dick 70 years after its first publication, the arrival of a proper edition of Emily Dickinson’s work 60 years after her death, and so on. Those authors, said Gizzi, “were writing into the hegemony or the totalizing effect of British canonical literature, were discovering my language, the American language, with its promise, its failures, its homely motor, and its homespun condition of a developing literature. I’m not waving a flag, I’m just stating a condition of discovery.” As I read this, I wondered about the relationship between the American language—the homemade language of Lincoln, Melville, Dickinson, Whitman, Pound, W.C. Williams, Hammett, O’Neill, Faulkner, Olson, Creeley—and the American cinema.

Foxcatcher (Bennett Miller, 2014)

We tend to think of early American cinema as foundational to the art form of cinema in general (rightly so), and of the popular medium of the movies as a dynamic reflecting mirror to the transformation of the country through the ’50s and ’60s—per Bazin, this was our “cinematic genius.” And we tend to mingle these two parallel narratives, that of the art of cinema and that of the growth of popular entertainment. The “homespun condition” described by Gizzi, and by Creeley and Olson and Williams and Whitman before him, rejects the obligation to mirror or embody American progress: one might argue the point when it comes to Whitman, but in his case it is a choice as opposed to a duty, a matter of potentiality rather than actuality. In other words, there is nothing but the ongoing action of defining one’s own ground and imagining one’s best self into being. As Williams writes in the opening sentence of In the American Grain: “Rather the ice than their way: to take what is mine by single strength…” We can instantly associate such a definition of freedom with Brakhage, Conner, Baillie, and Dorsky, but with Hollywood directors it can seem like a bit of a stretch. But didn’t the greatest Hollywood artists give us something far more fragile and beautiful than a national mirror? And where is Gizzi’s “homespun condition”? Does cinema give us an equivalent, or a parallel?

Or, per the quote above from Nicholas Ray, a director once famously identified with the cinema itself, are literature and cinema one and the same?

The panic of literary critics and Godard’s declarations aside, have words and images ever truly been at war? Does the idea that they are, or ever have been, amount to more than a matter of fashion? The cliché persists that images are shallow while words run deep, that novels allow us to enter the minds of the characters while movies merely show us what they do, and so on. In the age of moving images, this particular prejudice is no longer pervasive. All for the best. But as someone that grew up in a culture pegged to the written word rather than the image, I am still shocked by the rapidity with which the valence shifted. Of course, the writing, so to speak, was on the wall.

I remember sitting in a P. Adams Sitney lecture at Cooper Union in 1982, in which he offhandedly mentioned that he‘d once been asked to teach a class on Italian cinema. He agreed, he told us, on the condition that the class would begin with a reading of The Divine Comedy. This sent shivers down the spines of everyone in attendance. My reasonably well-educated friends and I reckoned that Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and Kerouac aside, “literary” meant old and musty. The word “intellectual” conjured images of interminable lectures about the joys of iambic pentameter delivered to women’s clubs. To be an intellectual was to remove oneself from the flow of life, and our nervous systems pulsed with the urge to return to zero (the horrific overtones of the term aside), to unburden ourselves of the weight of so much history and writing and float on the electric currents of images and sounds.

Meanwhile, the country at large was transformed in a way that suggested a horrifying parody of our youthful desire to transcend reality. I get the shudders whenever anyone musters up so much as an ounce of fondness for Reagan or his two terms in office, the unhealthy temper of which was captured perfection in Foxcatcher. An all-pervading sense of unreality rolling in like a weather system. If a fact was inconvenient, it was recharacterized as an opinion, and if the point was reiterated then the debater was an “elitist.” Jefferson and Madison were suddenly pious Christians and Tolstoyevsky was a Communist. “America”—the glorious realization of an impossible dream carried aloft on the wings of a shining promise—had regained its “spirit,” and if you challenged the point you were a loser. On the flip side was the world of academia, whose history and literature departments, per Todd Gitlin, were filled with veterans of America’s battered left wing, which had “squandered the politics but won the textbooks.” As if overnight, all of Western history and literature was recharacterized as one great artifact to be reconsidered from our supposedly enlightened vantage point by means of something called “theory.” Michel Foucault deserves the last word: everyone these days knows how to deconstruct texts, he said, but no one knows any texts. Literature, stranded between these two divergent paths to conformism, seemed to fade into a ghostly afterimage—a structuring absence, so to speak. We’re living in the afterglow of this unlucky alignment of the stars. The term “post-literate” is now employed with regularity, the audiovisual is now regarded as a remedial tool for those who are supposedly beyond hope of reading, and Harold Bloom is worried that “the light of the book . . . flickers and threatens to go out in the glare of visual media.”

So much for the word, but great news for the cinema. Right?

Bloom’s worry is understandable: the visual is now omnipresent. But that’s the visual, as opposed to the cinematic. The written word is also omnipresent. But we are drowning in a sea of words, as opposed to literature. The difference is that there’s none of the mixing and matching in literary culture that is still common practice in the world of cinema. No one spends any time bundling Ben Lerner and Susan Howe together with Stephenie Meyer and E.L. James, but in film criticism there’s still a lot of worry about where and when to draw the line between the Dardenne Brothers and London Has Fallen—in fact, doesn’t Kristen Stewart chide Juliette Binoche in Clouds of Sils Maria for exactly that? We’ve grown used to equating the excitement of cinema with its impurities, with the model of art secretly made under the cover of crass commercialism, with the critic panning for gold among piles of dross.

The Clouds of Sils Maria (Olivier Assayas, 2015)

But all of the aforesaid conditions are dead and gone. What we refer to as cinema—for lack of a better description, the nuanced articulation of image and sound—is no longer a great popular art form. The cinema has now diverged from the greater entity of worldwide audiovisual entertainment, where artistry is far more suspect and less welcome than it was in the heyday of Harry Cohn and Louis B. Mayer. It is also further than it would seem from episodic TV, no matter how good: concision is one thing and sprawl is something else. It seems to me that we’ve now finally arrived at the moment when the cinema has become, or is fast becoming, a specialized practice, far more likely to turn up in a museum or on a streaming service or within an as-yet-unformed communal setting than in a multiplex. It is already becoming a much lonelier undertaking. And lovers of film are now the modern equivalents of Thomas Pynchon’s Trystero adherents, dropping their communications into camouflaged underground mailboxes.

Obviously, big-budget entertainment and artisanal movie-making will continue to share the odd characteristic and certain artists will overlap. It‘s a fool’s game to try to build some kind of theoretical border fence around the art of cinema. But I do think that the change in the situation of American cinema calls for a refinement in the way we describe it. The kind of implicit ongoing dialogue between audience and filmmakers that held from the 1920s through the ’90s no longer exists—that is now the province and the great strength of episodic TV. The cinema is now a series of isolated artistic gestures, so the old auteurist idea of hunting for the evidence of personal expression in this or that movie no longer makes sense. And as writers about film, we have a bag of rhetorical maneuvers (ideas of geometrical spatial organization that turn every director into Hitchcock; a habit of zeroing in on certain details and thus isolating them from the whole enterprise; enumerating allusions and associations; form as illustration of content; enumeration of sociological/cultural symptoms) that are no longer of much use.

Given the enormous changes in cinema, we need to rethink our priorities. We should stop worrying about whether or not we’re paying sufficient attention to popular culture or being elitist, or imagining ourselves as explorers hunting for the cinematic—we already know the cinematic. And we should stop prowling around the movie, reducing it to a series of easily legible syntactic units or rendering moralistic judgments about a filmmaker’s intentions or demanding that every movie strike the correct cultural balance. We need to start revisiting the question of value, which leads directly to exactly what a given film is bringing us, not in a windy and broadly evocative sense, but in a very specific sense.

We‘re used to thinking of the relationship between form and content as one of realization or amplification. But how often is this really the case when it comes to the work that we care about? Isn’t it rather a matter of one continuous action? On this level, it’s not really a matter of translating a pre-existing script into images, but as Kubrick put it, preserving the original spark through all the contingencies that are thrown at you. Big-time narrative moviemaking is very different from writing and painting when considered strictly according to its logistics, but no different at all in the matter of refinement, articulation, and modulation. All the planning and scheduling goes into protecting what is most fragile, somewhat akin to transporting an ancient relic across a battlefield. “A poem is energy transferred from where the poet got it,” wrote Olson in his 1950 essay “Projective Verse,” “by way of the poem itself, all the way over to, the reader.” Substitute film, filmmaker, and viewer and you have a pretty succinct description of the circumstances behind great filmmaking.

I like Olson’s extension of the idea, pushing the writing of poetry and by extension the making of all art away from the fixed and toward the fluid, and I love his identification of the syllable as opposed to the line, the stanza, or the image as “king” in literature. “It is by their syllables that words juxtapose in beauty,” writes Olson, “by these particles of sound as clearly as by the sense of the words which they compose.” Here is where the division between film and literature not only breaks down but disappears altogether, where The Lusty Men and Wagon Master, Light in August, and Paterson, Charles Ives and Steve Reich find their common ground.

In Lea Jacobs’s Film Rhythm After Sound, we have a line of thinking that runs in close parallel to Olson‘s essay, by taking the emphasis off of “the shot” or “the frame” and rather identifying res, mass movements, shifting angles of vision) that filmmakers employ as rhythmic stops, switches, and points of inflection and articulation. If there is such a thing as a “unit” in filmmaking, it’s not strictly visual, but rhythmic in nature: it can come from anywhere across the cinematic spectrum. This harmonizes nicely with one of the most famous ideas in film theory, Eisenstein’s third image or meaning—his “intellectual” variation of Kuleshov’s “emotional” experiment. Actually, it’s Scorsese’s citation of the third image as a fundamental characteristic of the actual process of filmmaking that is finally of greater interest and practical importance. That’s where rhythm opens the door to wonder. Remove a frame here or two frames there, and the sense of it changes dramatically. Artistry in movies has never been about imprisoning us within the visual, any more than poems have been designed to enclose us in a web of words. They open out.

Inherent Vice (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2014)

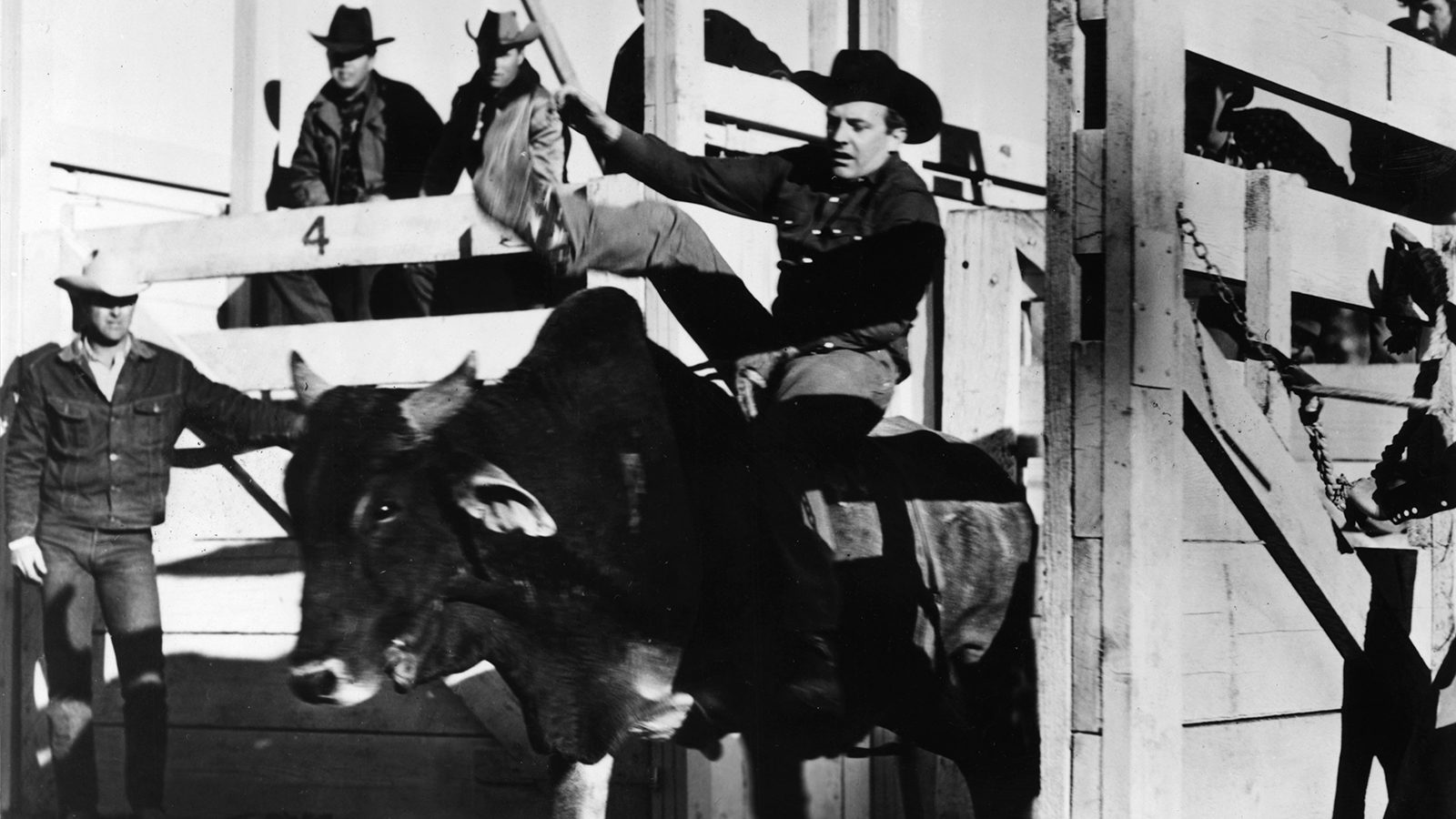

Gizzi’s homespun American condition can be found here, I think, in the jagged rhythms toward which a certain strain of moviemaking has been edging. One sees its beginnings in the studio era, with certain directors fighting their way through studio-dictated glamour and smoothness of line, just like the poets who had to get past the overwhelming effect of the English canon Eliot). One can see it in latent form in Kazan’s films, and in Ray’s movie, one of his most beautiful. At the beginning of The Lusty Men, after Robert Mitchum is thrown at the rodeo, there is a dissolve, and he slings his duffle over his shoulder and hobbles his way alone across the windswept arena, and we are given to understand that we are now watching a ballad of desolation. The road. Mitchum is dropped off. He walks up a familiar rise and the film gently steers us into another register. The movement is that of a parabola curving down toward abjection with the broken hobble and the blowing trash, and then gently up with Mitchum’s lonely return to the homeliest of homesteads: the approach, the walk past the gate, the look around at the decrepit structure, the crawl under the cellarless house and the remembered action of reaching in through the cobwebs for hidden treasures from ages ago. With Ray it’s always the unbroken movement, the music of inevitability, and the memory of this little scene will later stand in contrast to the close and tense encounters in tiny kitchens and clubs and hotel rooms and trailers, where the intensely alert eyes of husbands and wives and covetous hangers-on in the rodeo world become visual touchstones. The scene does what literary critics have always claimed films are incapable of doing: it opens our imaginations to realms beyond what we’re simply seeing, acres of sadness and smallness.

It is only later, with the revolution in acting that began in the ’50s and the spirit of discovery that it provoked between directors and actors, that we really find the kind of proudly spiky, halting, close-to-the-ground American voice in cinema that Gizzi is describing, sustained from beginning to end. Cassavetes is the obvious groundbreaker. Too much continues to be said about his “improvisational” emotionalism and not enough about his meticulously wrought rhythmic compositions of scenes. When the French film theorist Nicole Brenez (correctly) described Cassavetes as a great editor, this is what she meant: the percussive pinging and ponging between gestures and offhand remarks and spells of quiet broken by wildly impulsive rants, staking entire scenes on facial expressions, changes in skin tone, the most minute behavioral beauties. Cassavetes is projective, all right, but inward, getting close, closer, closest to the molecular substructure of human interaction. Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky, often lumped together with Cassavetes’ own films for obvious reasons but finally several miles away, seems more astonishing now than ever. Every shot is a separate event, a movie in miniature, and every scene, practically every moment, is a seemingly impossible continuity built from a million discontinuities, the rhythm simultaneously broken down and improbably flowing and surging forward—in some ways the ultimate fulfillment of the compliment that Orson Welles paid to Raging Bull: “Movies should be rough.” The line of every scene is unbelievably fragile, always seemingly on the verge of falling apart, far more so than in Cassavetes’ cinema, and the endless shifts within a sustained moment are like a constantly ringing call to wake up to life—open your eyes, you’re going to miss something! Where Cassavetes stays within a strictly domestic universe, May’s determinedly tawdry, desperate urban universe keeps expanding and growing like crystal in the mind.

Here are the two artists that opened the way for Raging Bull and the precarious balance between chaos and control in The Tree of Life and Malick’s new Knight of Cups, in The Master and Inherent Vice, in Listen Up Philip and Heaven Knows What, and in Foxcatcher. These are films made by artists who take the common interrelated sensory elements of everyday life, the clangs and sighs and sashays and swivels and everything else visible and audible under the sun, and, to paraphrase Williams, compose them without distortion into such an intense expression of their perceptions that they may constitute a revelation.