In Every Dream Home

Todd Haynes’s latest film, Far from Heaven, is a reworking of Douglas Sirk’s 1955 film All That Heaven Allows, previously remade in 1971 by Rainer Werner Fassbinder as Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. In Sirk’s film, an upper-middle-class widow (Jane Wyman) falls in love with her gardener (Rock Hudson). Shunned by her children and her friends, she breaks off the relationship only to realize, perhaps too late, that she made the wrong decision. As Fassbinder wrote, “If anyone has made their love life this complicated for themselves they won’t be able to live happily ever after.” This from a man who never portrayed love as anything but complicated, its almost inevitable doom sealed by basic human drives, configured through the ideology of what used to be called “late capitalism” and is now Capitalism Unbound.

And yet, Fassbinder, like Sirk before and Haynes after him, found hope—and a reason to make films—in resistance expressed not directly but through dramatic irony arising from their description of the world as it is and an implied vision of what, ideally, it could be. (Consider the titles All That Heaven Allows or Far from Heaven.) This classical form of irony, characteristic of all three filmmakers, also involves a discrepancy between the awareness of the characters and that of the audience. But rather than merely putting the audience in a superior position, this difference makes them more acutely aware of the commonality between their own dilemmas and those enacted on the screen. In melodrama, the genre to which these three films belong, that commonality is further emphasized by the use of certain expressive elements (music, color, lighting) that play on the emotions. “I wanted to make a film that would make you just weep,” said Haynes, and indeed he has, although you won’t weep as convulsively as you might in some of Sirk’s films.

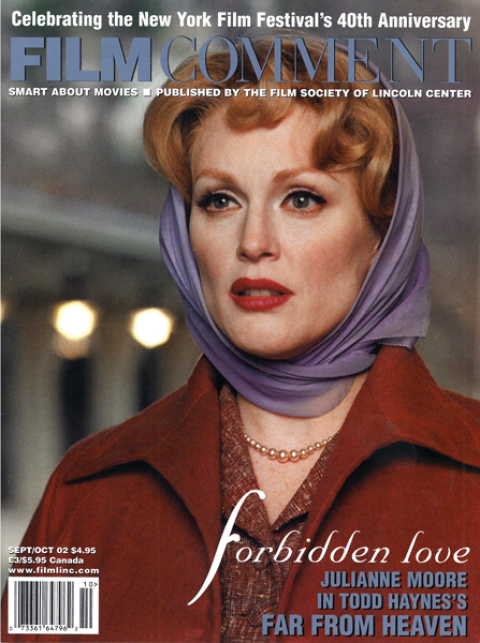

Irony, in this sense, has little to do with the current use of the term to describe the mix of parody and cynicism that dominates popular entertainment today. “We’re in this incredibly cynical, emotionally guarded moment in American culture, especially in youth culture,” says Haynes, explaining why he’s nervous about how Far from Heaven’s combination of extreme aestheticism and emotional sincerity will be received. Far from Heaven is Haynes’s fourth feature, and since its budget (roughly $14 million) is double that of Velvet Goldmine (98), and seven times that of Safe (95), how best to position it in the marketplace is a cause for concern for its distributor, Universal Focus.

“What I learned from the test screenings—ridiculous as the test screening situation may be—is that this film does exactly the opposite of what audiences want today,” says Haynes. “They want something that on the outside seems real and authentic—even though we know these codes of realism change historically, so that when we look back at films that were supposed to be realistic they look, oh my God, so fake—but where people act heroically. They want a heroic ending. They want this bullshit. They don’t want to see people who act like us, who are feeble and fearful and limited and can only take tiny steps toward their desires.”

You can read the complete version of this article by purchasing the September/October 2001 issue of FILM COMMENT.