The Great Divide

Sometime during the honeymoon phase of the Obama era, there was a multiplex pre-roll promo that depicted moviegoers of various races sitting together in a theater, taking in the assimilating raptures of the screen with fresh-faced, uniform sanguinity. We’re all the same in the dark, or so the tagline may as well have read. It would have been absurd to feel affronted by such contrived naïveté, which after all was just another example of branded, Benetton-style pluralism patting itself on the back in an allegedly post-racial world. What did sting, though, was the realization that even this hollow gesture was hard-won, that this recognition of racial unity in a public space would have been inconceivable just a half-century before. If classic Hollywood had ever tried being kinder to people of color, such a utopian fantasy might have asserted itself with greater force much earlier in our history—perhaps as an outgrowth of the idea, propagated in films like The Crowd and Sullivan’s Travels, that the movies are where we go to escape the real-world contingencies that isolate us from one another. When we talk about the communal enterprise of moviegoing, the underlying assumption still seems to be that, in surrendering to the universality of the screen, we should hold all of our inconvenient identities in abeyance.

One imagines James Baldwin would have had none of that. In his most sustained commentary on cinema, the 1976 book-length essay The Devil Finds Work, he gives voice to the suspicion and anger that many movie lovers feel toward an art form that not only fails to represent them but insists on slandering them at every turn. One of Baldwin’s most boldly digressive works, the essay shifts between recollections of childhood, accounts of the writer’s own experiences in the movie industry, and unsparing interpretations of the racial knowledge inscribed in everything from the “straight, narrow, lonely back” of Joan Crawford to the respectability politics of Sidney Poitier. At the heart of these scattershot musings is a liberating idea that flies in the face of film criticism’s traditional reliance on textual exegesis and aesthetic appreciation. For Baldwin, cinema opens the mind up to a kind of free-associative soul-searching. The experience of a film lives at the intersection between an entrancing, dreamlike medium and each viewer’s own incoherent repository of hopes, fears, memories, and moral convictions.

Anyone married to the belief that critics should stick to parsing what’s on screen will balk at the rhetorical leaps that Baldwin takes with a film like The Exorcist, whose “mindless and hysterical” conception of evil prompts him to rail against the graver horrors of racism, poverty, and war. Yet who would deny that the ability to evoke such subjective, even willful responses—which have everything to do with those identities we’re called to relinquish in the darkness—are what give movies their power to wound and enrage? If the photographic properties of film, as Bazin argued, guarantee “an image that is a reality of nature,” then for viewers of color it can only be a dystopian nature, one in which almost all meaningful traces of one’s own people have been debased or omitted.

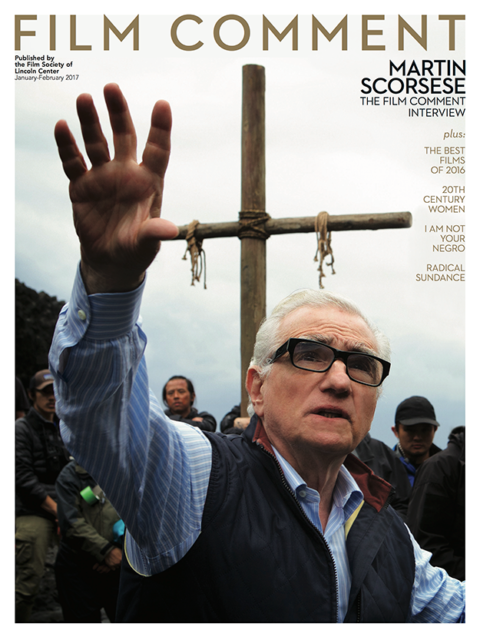

Joseph Mankiewicz and James Baldwin merging with the crowd, © Dan Budnik

In some of the most striking passages in the new documentary I Am Not Your Negro, director Raoul Peck implicitly connects The Devil Finds Work with the tradition of Marlon Riggs’s Ethnic Notions and Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, films that reimagine cinematic history as a site of racial excavation. Peck’s film sets out to make use of the unfinished manuscript of Remember This House, Baldwin’s late-career attempt to grapple with the deaths of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers, but it soon abandons this premise for the kind of emotional detours that give some of Baldwin’s best work its freewheeling, capacious spirit. One of the film’s strategies is to pair the voice of Samuel L. Jackson intoning selections from Baldwin’s writing with relevant images salvaged from American history, including segments that highlight the white supremacy encoded in Hollywood narratives. With Baldwin as his guiding light, Peck delivers an indictment of cinema that ultimately covers more ground than either Riggs or Lee did. He’s not just identifying moments where pop culture’s twisted racial logic is made blatant, as in King Kong or John Wayne westerns or the career of Stepin Fetchit. He’s suggesting that, for those who internalize the pain of these offenses, the comparatively innocent whiteness of someone like Doris Day looks like nothing less than an emblem of moral rot.

There’s a studiousness to I Am Not Your Negro that serves as a counterpoint to Baldwin’s impassioned, off-the-cuff soliloquies, which take the spotlight in several excerpts from the writer’s TV interviews and public appearances. Peck balances the sometimes explosive heat of his star with an arsenal of footage, photographs, and text, unleashed in brilliantly edited bursts that call to mind the cumulative power of Leo Hurwitz’s leftist documentary classic Strange Victory. Among the artifacts on display are images of racial violence across the decades, some of which seem to have been chosen for their numbing familiarity. Peck also seamlessly integrates the terrifying iconography of our Black Lives Matter era (a video of Eric Garner, a photo of Trayvon Martin), disregarding the distinctions between past and present that have sometimes caused friction between black activism’s old and new guard. In perhaps his trickiest maneuver, Peck interweaves impressionistic shots of contemporary America—of highways, train tracks, and the consumerist spectacle of Times Square—to imply that, when you exist as a racialized subject, it can be difficult to go anywhere without projecting the anxieties of one’s oppression onto the landscape. Once examined, the specter of racism is hard to unsee.

If there’s an overriding tone that emerges from this assemblage of found material, it’s one of spiritual weariness. Due to the exigencies of transforming hearts and minds, most American documentaries about racism adopt a mood that can galvanize an audience into action, typically landing on a note of empathy or outrage, or, in the case of Ava DuVernay’s recent 13TH, a tightly constructed sense of factual mastery. But watching I Am Not Your Negro four long years after the death of Trayvon Martin, and mere weeks after the election of Donald Trump, it’s hard to ignore the question that Peck and Baldwin have left unanswered: where does all this evidence get us? For centuries, anti-racist movements of various ideological stripes have hinged on the belief that public opinion could be shaped by the dissemination of certain persuasive truths. For towering figures like Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington—those who were touted as “extraordinary negroes” in the press and political establishment—the focus was on rendering irrefutable the intellectual equality of black people. In the past half-century, we’ve seen a new emphasis on uncovering, at ever-increasing degrees of intimacy and veracity, the realities of white violence and black suffering. As our national mythology would have it, it was not until Bull Connor unleashed dogs and fire hoses on black protesters in 1963 that white people had the chance to come to grips with the evils of Jim Crow. We are accustomed to thinking that if only the truth would out itself, the world could be so different—as if this truth had not already been in plain sight.

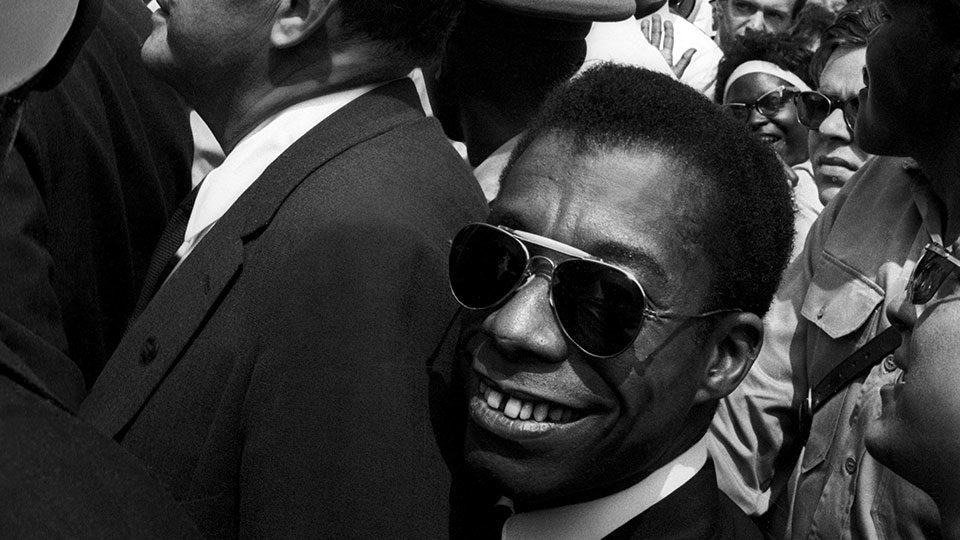

"Two Minute Warning," Spider Martin, 1965

We live in a time that has proven to us, again and again, that all the visual evidence in the world will not lead to the conviction of those who have killed unarmed African-Americans in cold blood. In the face of this futility, it’s tempting to feel nostalgic for some dreamed past in which the political efficacy of the self-evident might have seemed on sturdier ground. I Am Not Your Negro does not succumb to such nostalgia. Echoing the powerful 1982 documentary I Heard It Through the Grapevine, in which an aging Baldwin journeys through the Deep South to take stock of the little that has changed in the decades since the civil rights movement, Peck’s film burrows deep into the contradictions of a nation in which the sheer inertia of social change has been disguised by feel-good monuments and heroic symbolism. The film also shares its dejected mood with other recent odysseys through racist America, most notably Arthur Jafa’s lyrical documentary Dreams Are Colder Than Death, which captures the feelings of disorientation and fatigue that racism induces in its victims, and Claudia Rankine’s extraordinary prose poem Citizen, which documents a series of everyday microaggressions with crisp, almost clinical immediacy. If the average American has been taught to envision the arc of the universe bending toward justice, then Baldwin’s restlessly self-questioning voice offers a counterargument to such deeply ingrained moral certitude, an admission of doubt uncannily aligned with some of the defining anti-racist works of our moment.

The recent resurgence of interest in baldwin has admittedly robbed I Am Not Your Negro of some of its sense of discovery. And since the film is structured to always take him at his word, it ends up smoothing over the complexities of a writer who always seemed at odds with his own impulses. The great risk of applying Baldwin’s words to our present-day horrors is that it lends his work an undue semblance of prophecy. But Baldwin was no clairvoyant, and this false projection only allows us to interpret the persistence of injustice as somehow inevitable, deflecting our collective responsibility to eradicate the ills he diagnosed. When we listen to Baldwin disassemble the logic of racism, as this film gives us ample chance to do, we are responding not to the man’s foresight but to his courage to speak from within the specificity of his own time and place. As we hear in his words on the voiceover, Baldwin was reluctant to align himself with the class aspirationalism of the NAACP, the aggression of the Black Panthers, or the piety of the Nation of Islam or the black church. For this, people like Eldridge Cleaver accused him of being a sycophant starved for white approval. And yet Baldwin’s resistance to being taken for an obedient mouthpiece for the movement is everywhere to be seen in the ferocious way he plays his audience and dominates each space he enters, swooping his arms through the air, taking flamboyant drags from a cigarette, and, as a former junior minister, modulating his church-honed cadences to land a particularly righteous punch line.

In his wide and wicked smile, you can see that Baldwin knew he was destined not just for the page but for the camera. Despite the imperiousness of his on-screen persona, his vulnerability lay in a transparent need to be understood by his listeners, including the white ones. It was not a contradiction for him on the one hand to openly pity white people for their moral deficiencies (“There is little in the white man’s public or private life that one should desire to imitate,” he wrote in The Fire Next Time), while on the other acknowledge them as loved family members whose betrayal he longed to one day forgive (“We, the black and the white, deeply need each other”). This push-pull between rebuke and reconciliation is what makes even a resolutely disillusioned political documentary like this one inherently frustrating. Baldwin famously expressed disdain for the narrow confines of the protest-art tradition, but even his writing cannot avoid the desire to connect with the same oppressor from whom he must also establish an unequivocal independence. Similarly, for all the catharsis that some viewers of color may experience upon seeing their reality corroborated on the big screen, it’s hard not to feel like Peck’s address—for better and for worse—is squarely directed at an imagined white “you,” whose emotional response to the material will serve as a measure of its effectiveness.

“When you lookin’ at me, tell me, what do you see?” spits Kendrick Lamar on To Pimp a Butterfly, the Album of the Moment that I Am Not Your Negro invokes over its closing credits. For many people of color, the line registers as a purely rhetorical question intended to rouse the addressee; the answers, after all, are already known by the asker. In one startling scene near the end of the film, Peck all but re-creates this question with a series of shots of black people staring directly into the camera as if standing their ground, presenting the white “you” with visual evidence of themselves. The emotions that surface across their faces range from heartbreak to rage to steely self-assurance. It’s an unbearably fraught moment, one in which the subjects seek to convey their autonomy and humanity, but one whose dynamics are invariably governed by the question of how to prove the depth of one’s emotions to the historically unfeeling white onlooker. And yet it’s in the imagining of what it would mean for each of these gazes to be returned that the echoes of Baldwin’s words finally take on their devastating cinematic force.

Closer Look: I Am Not Your Negro opens on February 3.

Andrew Chan has been contributing to Film Comment since 2008.