In writing to President Johnson in December 1965 about his intention to make a film about the Green Berets, John Wayne explained that it was “extremely important that not only the people of the United States but those all over the world should know why it is necessary for us to be there . . . The most effective way to accomplish this is through the motion picture medium.” He thought he could make the “kind of picture that will help our cause throughout the world.” According to Wayne, it would “tell the story of our fighting men in Vietnam with reason, emotion, characterization, and action. We want to do it in a manner that will inspire a patriotic attitude on the part of fellow Americans—a feeling which we have always had in this country in the past during times of stress and trouble.”

Unlike earlier wars, however, the Vietnam War did not unite the nation to a common cause, but tore it apart. Michael Wayne, who produced the film for his father’s company, claimed that The Green Berets did not tell a controversial story: “It was the story of a group of guys who could have been in any war. It’s a very familiar story. War stories are all the same. They are personal stories about soldiers and the background is the war. This just happened to be the Vietnam War.”

On its part, the White House willingly embraced the project. Jack Valenti, then an advisor to President Johnson, advised him that while John Wayne’s politics might be wrong, “insofar as Vietnam is concerned, his views are right. If he made the picture, he would say the things we want said.” Wayne himself freely admitted he was doing more than playing his usual soldier role. He saw the movie as “an American film about American boys who were heroes over there. In that sense, it was propaganda.”

Of all the filmmakers in Hollywood, whether Hawk or Dove, only Wayne was willing to take a financial gamble and make a movie about an increasingly unpopular war. But The Green Berets did not inspire other filmmakers to use Vietnam as a subject for war movies. In fact, until 1975, no one in Hollywood seriously considered producing a major theatrical film about the Vietnam conflict.

In the spring of that year, having completed his second Godfather film, Francis Coppola told an interviewer that his next movie would deal with Vietnam, “although it won’t necessarily be political—it will be about war and the human soul . . . I’ll be venturing into an era that is laden with so many implications that if I select some aspects and ignore others, I may be doing something irresponsible.” He told another interviewer that his planned film would be “frightening, horrible—with even more violence than The Godfather.“

As the vehicle for his explorations, Coppola selected John Milius’s six-year-old screenplay based on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Shifting Conrad’s story of civilization’s submission to the brutality of human nature from the jungles of Africa to Vietnam, the script told the story of a Green Beret officer who defects and sets up his own army across the Cambodian border where he proceeds to fight both American and Vietcong forces.

Throughout the film’s production, Coppola shifted his intended focus from an anti-war film to an action adventure film and back again. At one point, he characterized Apocalypse Now as pro-American, denying it was anti-Pentagon or even anti-war. During filming in the Philippines, he described Apocalypse Now as “anti-lie, not an anti-war film. I am interested in the contradictions of the human condition.” With his intellectual attraction to the good and evil that are inherent to all men, Coppola said that he was trying to make a war movie that would somehow rise above conventional images of valor and cowardice. When asked why he was attempting to show this in a film set in Vietnam, the director responded that it was “more unusual that I am the only one making a picture about Vietnam.”

In coming to the Pentagon with his plans in May 1975, Coppola told Public Affairs officials that his initial script would need considerable work, especially the end, which he considered “surrealistic.” While recognizing that the screenplay had considerable problems, the officials forwarded it to the Army with the recommendation that the service should work with the director so that the completed film “will be an honest presentation.”

The Army found little basis to even talk to Coppola, responding that the script was “simply a series of some of the worst things, real or imagined, that happened or could have happened during the Vietnam War.” According to the service, it had little reason to consider extending cooperation “in view of the sick humor or satirical philosophy of the film.” Army officers pointed to several “particularly objectionable episodes” which presented its actions “in an unrealistic and unacceptable bad light.” These included scenes of U.S. soldiers scalping the enemy, a surfing display in the midst of combat, an officer obtaining sexual favors for his men, and later smoking marijuana with them.

The military probably could have lived with at least some of these negative incidents if put in what it regarded as a realistic and balanced context. But, from the initial script onward, the Army strongly objected to the film’s springboard which has Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) sent to “terminate with extreme prejudice” Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando) who has set up an independent operation and is waging a private war against all sides. The Army said Kurtz’s actions “can only be viewed as a parody on the sickness and brutality of war.” The service maintained that in an actual situation, it would attempt to bring Kurtz back for medical treatment rather than order another officer to “terminate” him. Consequently, the Army said that “to assist in any way in the production would imply agreement with either the fact or philosophy of the film.”

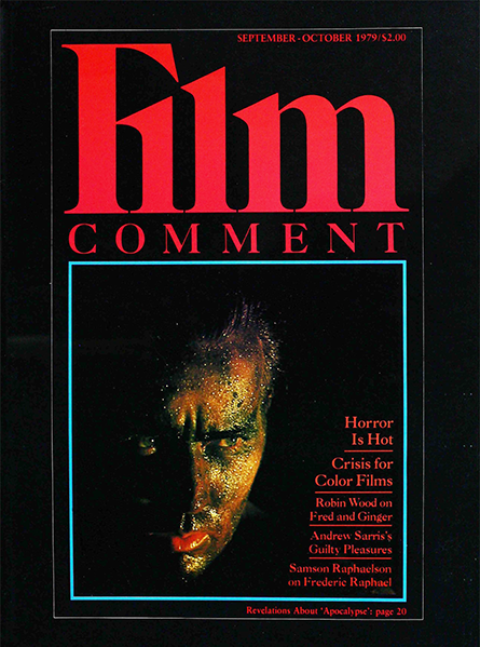

Although Coppola’s staff maintained intermediate communication with the Pentagon, Coppola made no immediate effort to modify his script in order to obtain even limited assistance. Instead, he went off to the Philippines to shoot Apocalypse Now, thereby beginning a struggle that was to last more than three years, cost more than $30,000,000, and come to resemble America’s conduct of the war. The film’s schedule release date proved as illusionary as the military’s regular predictions of victory as the opening was pushed back from April 1977, to November, then to December 1978, spring 1979, and finally, August 1979.

In the meantime, other filmmakers followed Coppola’s lead and began to create images of America’s Vietnam experience. In contrast, however, they chose to make their comments about the horrors of war, not through portrayals of violence, but by using the conflict as a starting point and as the villain which scarred individuals and the nation. By focusing on the victims of the war, these first movies continued the anti-war, anti-military movement of the Sixties and early Seventies.

The first effort to probe the war’s impact actually appeared more than two years before Coppola began working on Apocalypse Now. Limbo attempted its anti-war statement by portraying POW wives as the victims of the conflict. Not knowing when or if they would ever see their husbands again, the women found themselves shunted aside by a seemingly unfeeling Air Force and caught up in their own desires to live normal lives. The military refused to have anything to do with the production, claiming POW wives seldom committed the infidelities dramatized on the screen and arguing that the film would immediately be spirited off to Hanoi for showing to the POWs, thereby affecting their morale. In any event, the film suffered an unlamented demise not so much because of its dramatic shortcomings, but because its release coincided with the repatriation of the POWs in early 1973.

Ironically, Limbo made a direct visual connection to the first Vietnam film to appear in the post-war period. Limbo ended in a freeze frame of a returned POW reaching down an airplane ramp to greet his wife while her lover watched from the shadows. Rolling Thunder, released at the end of 1977, began as an Air Force Officer disembarks from a plane to greet his wife after eight years as a POW. Played by William Devane, the officer becomes the symbol for the destructive impact which the war had on individuals and the country.

His first night at home, while trying to comprehend the changes in his wife—her job, mini-skirt, and bralessness—she informs him that she has “been with another man” (the policeman who drove them home from the airport) and that she wants a divorce. The film explains Devane’s apparent lack of reaction, either of pain or of anger, by inserting flashbacks of North Vietnamese torture sessions. According to Devane, he survived by coming to love his enemy.

The impact of his captivity is even more fully illustrated by the arrival of a gang of Mexican-Americans in search of $2,000 in silver dollars which local citizens had given Devane after his return. The film intercuts his silence in the face of beating and torture (putting his hand in a garbage disposal) with scenes of his silence during torture sessions in Vietnam. When the gang kills Devane’s wife and son (who has become his only reason for living), it becomes the enemy he had not been able to fight in Vietnam, an enemy against which he can vent his pent-up rage for his eight years of torture and deprivation and, indirectly, his wife’s unfaithfulness.

The film’s producer’s request for limited assistance from the Air Force was flatly rejected and the Defense Department advised him: “There are no known cases of Air Force officers becoming schizophrenic as happens . . . in the story. Yes, there are cases of returnees coming home to marital problems, but there is nothing beneficial for the Department of Defense in the dramatization of this situation.” The Pentagon did acknowledge that there were positive elements in the officer’s stoic behavior while he was a POW, and in the early scenes of the film, he is portrayed as a loyal, dedicated officer. But clearly, the military wanted nothing to do with a film that conveyed the idea that Devane’s Vietnam experience contributed to his vengeful pursuit and carefully orchestrated slaughter of his son’s killers.

Reviewers found the violence excessive and audience ignored the film, having recently watched Charles Bronson play a similar revenge-seeking husband in the equally violent Death Wish. If Rolling Thunder passed from sight, however, it undoubtedly deserved a better fate. Its sparsely written script made telling insights into the changes that the Vietnam War had made on its participants and American society as a whole.

Heroes, also released in 1977, used the same veteran-as-victim thesis to convey its anti-war statement. But, in contrast to Rolling Thunder, it enjoyed some success due to its comedic approach and the presence of Henry Winkler (TV’s “The Fonz”), playing a demented Vietnam veteran who roams the country trying to find himself. According to Winkler, he played “a guy back from Vietnam who’s a little touched.” On the surface, the film was simply an offbeat love story and typical Hollywood “road” movie. On another level, however, Heroes attempts to convey the idea that Winkler’s craziness grew directly from his Vietnam experience.

The Army considered that Winkler was probably a little mixed up before his tour of duty, and so the war had little to do with his subsequent behavior. As a result, the service was not bothered by the film’s opening which showed Winkler’s insane efforts to drag potential enlistees from the grasp of a recruiting officer who was telling the youths that “war is better than sex.” However, before allowing the producer to shoot the film’s opening sequence in its Times Square recruiting station, the Army did make requests for revisions in the portrayal of the recruiting sergeant which make him “more sympathetic and place him in a defensive position, and have also made [Winkler’s character] the aggressor and unstable to boot.”

Following the surrealistic beginning, the film quickly degenerated into a romantic comedy filled with Winkler’s antics and efforts to woo Sally Field whom he had picked up along the way. In the closing sequences, however, the cause of Winkler’s insanity is finally visualized by means of a brief firefight during which his best friend is killed trying to rescue him. Thus the film does make the connection between the effect of the war on its participants and their subsequent behavior.

If the Army could ignore this message and give limited assistance to Heroes because it outwardly appeared to be a comedy, the armed forces have had a far more difficult time agreeing to cooperate on serious films dealing with the Vietnam experience. In making Coming Home, the producer sought assistance from the Marines “in the interest of authenticity.” In response, the service’s Office of Information found the script “interesting and will undoubtedly result in an entertaining and controversial film,” but felt it would “reflect unfavorably on the image of the Marine Corps.” The service objected particularly to the widespread use of drugs by officers and men and the commentary by an officer (played by Bruce Dern in the movie) about how his men cut heads off enemy bodies in Vietnam. As a result, the Chief of Information recommended that the Pentagon refuse to assist the production.

Although the film company made an inquiry about the rejection, it did not pursue the matter further with the Marines. At the same time, producer Jerome Hellman did seek assistance from the Veterans’ Administration. At first, the VA was cooperative, but communications turned “vitriolic” when the VA found that the script exploited paralyzed veterans and was “very offensive” to them. In responding to the second script, Dr. John Chase, the VA’s chief medical director, observed that the story “incorrectly and unfairly portrays veterans as weak and purposeless, with no admirable qualities, embittered against their country, addicted to alcohol and marijuana, and as unbelievably foul-mouthed and devoid of conventional morality in sexual matters.”

Although the VA’s position in regard to assistance on Coming Home changed when Max Cleland became its director in 1977, filming had already been completed. Unlike the armed forces, Cleland, himself a disabled Vietnam veteran, did not believe a critical portrayal of an organization is sufficient grounds to prevent use of facilities by a “legitimate” filmmaker: “If it is in the broad range of legitimate filmmaking, just because it portrays the VA in a bad light or case VA physicians or nurses in a bad light, that is in my opinion not enough reason by and of itself to say perforce, you cannot film it on location.” In fact, Cleland demonstrated a trust in the integrity of filmmakers that the military seldom showed in all its years of assisting in the production of war movies. The head of the VA felt that Hollywood had good intention and tried to tell its stories fairly.

Coming Home itself seemed to support Cleland’s contention. Despite the problems the VA had with the screenplay, he found that the completed film provided hope for disabled veterans, and so he loved it. After seeing the movie, Dr. Chase observed that he would probably have agreed to assist on its production if the initial script had reflected the movie’s final form. In reality, Coming Home offers a viewer a variety of images, perhaps reflecting the many inputs into the production from Jane Fonda, the several screenwriters, the producer, and the director.

While the filmmakers clearly intended that the movie make an anti-Vietnam statement, the message became lost somewhere along the way. Most obviously, the message came at least ten years too late. No one in the country, even those who most strongly protested the war, really cared about the conflict in 1978, at least as a “cause.” Even as an anti-war film, using the “victim” theme to convey the message, Coming Home pales in comparison to Fred Zinnemann’s The Men (1950).

Telling the same story of the struggle of paralyzed veterans to adjust to their disabilities, Zinnemann conveys the harsh reality that the men’s injuries are irrevocable and must be accepted, that they will never walk again and never be able to perform sexually. In contrast, watching Coming Home, the audience almost expects Jon Voight to jump out of his wheelchair à la Dr. Strangelove and yell, “Jane, I can walk! I can make real love!” Moreover, the film played down the destructive impact the war had on Bruce Dern. The audience is provided few insights into the causes for a gung-ho Marine captain to disintegrate into a suicide-bent wreck.

If the film wastes the strong anti-war statement inherent to Dern’s character, it badly dilutes the powerful climactic anti-war monologue which Voight delivered to a group of high school students. As Voight describes what the war did to him and the country, scenes of Dern’s clichéd Star Is Born suicide are inter-cut into his diatribe, seriously weakening its impact. In the end, therefore, Coming Home becomes a trite love story with a now-possible happy ending rather than a significant portrayal of the destructiveness of the Vietnam War.

While Limbo, Rolling Thunder, Heroes, and Coming Home focused on returned veterans to suggest that war is hell and Vietnam was even a worse hell, other films in addition to Apocalypse Now took the more traditional approach of allowing combat itself to convey an anti-war, anti-Vietnam statement. But however bloody and violent filmmakers have portrayed combat on the screen, the action and excitement usually have become escapist entertainment rather than creating a revulsion against war. The first two pure combat movies of the post-Vietnam war era fell victim to the paradox of trying to make an anti-war statement using war as the vehicle.

Despite the claim of Max Youngstein, the American consultant to the Singapore-based Golden Harvest Company, The Boys in Company C contained, at best, only a superficial denouncement of Vietnam. Realizing that any film which would advertise itself “To keep their sanity in an insane war, they had to be crazy” would have no appeal to the Pentagon, the film company did not even submit a script to the Defense Department. Instead, it shot the movie in the Philippines, ending up with a story that Marine officials insisted bore almost no resemblance to their training procedures, activities, or experiences in Vietnam. And because the movie imitated M*A*S*H and countless other war films of earlier eras while saying nothing unique about Vietnam, audiences generally ignored it.

In contrast, Go Tell the Spartans made a serious effort to look at the American combat experience in Vietnam. Set in the early Sixties, the film focused on the role of U.S. advisors working with the South Vietnamese army. The Defense Department Public Affairs office found the script “unusual” in that it showed the advisors “heroically carrying out their assignment.” The Army, however, had problems with the story because the script presented “an off-hand collection of losers” making up the American unit at a time in history when advisors in Vietnam “were virtually all outstanding individuals, hand-picked for their jobs, and quite experienced.” Since Army regulation required that the service be presented realistically, the Information Office informed the Defense Department that for the film “to qualify for assistance, all characters in the script would have to appear as outstanding soldiers; no drug use, no ‘Lt. Fuzz’ characters, and no draftees.”

Objections relating to alleged factual inaccuracies might have been resolved in direct negotiations with the filmmakers. Throughout the history of the relationship between Hollywood and the armed forces, most requests for script changes have related to technical inaccuracies and filmmakers are usually happy to correct mistakes to insure authenticity. At the same time, the military has always recognized the need for dramatic license and accepts situations which may stretch military procedures as long as the characters remain plausible.

With Go Tell the Spartans, however, an irreconcilable problem did exist. The Army could not accept the characterization of the movie’s central figure, a major played by Burt Lancaster, and the filmmakers refused to revise the role. Apart from objections to Lancaster’s language and drinking, which were compromisable matters, the Army pointed out that a man of his age and years in the military (a veteran of World War II and Korea) would have been promoted or have left the service.

The screenwriter, Wendell Mayes, agreed with the criticism and acknowledged that the Army was justified in refusing to assist on a film with a factually implausible central character. At the same time, he explained that he and the producer refused to consider changing the role to obtain assistance because they liked the way Lancaster describes the reasons he had remained a major. Talking to one of his subordinates over a bottle of liquor at their jungle headquarters, Lancaster recounts in great detail and much humor his misfortune of having been discovered making love to a general’s wife in the gazebo of an embassy by the general, the ambassador and his wife, and the President of the United States. While Mayes conceded that Lancaster would summarily have been thrown out of the Army, the screenwriter said Lancaster’s explanation on the screen was worth the price of not obtaining assistance, which was not absolutely essential to the production in any case.

Despite such dramatic license, Go Tell the Spartans did in large measure become a tribute to the Army’s advisors in the early days of the war. The climactic firefight created the feel of real combat, unlike the major battle in The Green Berets which looked like a typical John Wayne versus the Indians shootout. As a result, the film has come the closest of any film about Vietnam yet released to capture the American experience in the war. Nevertheless, like The Boys in Company C, Go Tell the Spartans failed to attract a large audience and quickly passed from view despite praise from critics and the military.

Not until The Deer Hunter appeared did the war itself become a financially viable subject for filmmakers. By its very size and sweep, the film would have commanded attention. Perhaps impressed by the effort, perhaps equating excellent performances and camerawork with meaningful insights, reviewers rushed to acclaim the movie as one “of great courage and overwhelming emotional power,” “a fiercely loving embrace of life,” “the great American film of 1978,” and “one of the boldest and most brilliant American films in recent years.”

To some, it may not matter, as it did to the Army, that the film shows the United States withdrawing from Vietnam in “a Dunkirk-type bug-out” which was “associated with the fall of the South VN government” even though the American troop withdrawal was actually completed two years before the fall of Saigon. But others would find it difficult to ignore history and be drawn into the desperate search Robert De Niro undertakes for Christopher Walken, knowing that no U.S. soldiers returned to Vietnam in the last days of the war.

Far more important, the director misses the point when he says, “I don’t dispute the accounts of My Lai 4, but I think that anyone who is a student of the war or anyone who was there, would agree that anything you could imagine happening probably happened.” Atrocities do happen in war and the Vietcong undoubtedly committed atrocities of the type Cimino portrayed. But My Lai became so crucial to the American perception of Vietnam because United States soldiers committed the massacre.

Ultimately, however, The Deer Hunter fails to capture the essence of the American tragedy in Vietnam not only because it distorts history, but because its central metaphor, the recurring game of Russian roulette, is a lie. Initially, audiences and reviewers accepted the authenticity of the game. According to one critic, it apparently “was played in Saigon and other parts of Southeast Asia as well. It was a parlor sport of some sort.”

In fact, no evidence exists that any POWs played any form of Russian roulette while in captivity. Nor was it a betting game in Vietnam. If audiences cannot accept the validity of the Russian roulette imagery, then they cannot, in the end, accept the validity of the people in the film. Cimino said that his only hope for the finished film was that audiences “really love” his characters, “nothing deeper than that. I want people to feel they would like to go on knowing these characters. I guess I want them to believe in the validity of these people.” To the extent that audiences did so, it was due to the quality of the actors’ performances. But, instead of seeing their rousing singing of “God Bless America” as confirming their love of the country as the director intended, it becomes only one more ambiguity in a film filled with conflicting images.

While the Army undoubtedly appreciated Cimino’s reversing roles in the My Lai massacre, the service could find no benefit in a script with such a comment and with its many technical and historical errors. In turning down a request for assistance, the Army recommended that the producer “employ a researcher who either knows or is willing to learn something about the VN war.”

The Army did not even make that suggestion in refusing to assist in the production of Hair, simply stating that “No benefit to the Army is apparent in the script” and that the service “is not presented realistically.”

And despite several months of negotiations, the services refused to either reconsider their decisions or even explain them in writing. Ultimately, Jack Valenti, president of the Motion Picture Association of America, interceded on behalf of the filmmakers. As a result, after discussions at very high levels in the Pentagon, officials worked out a compromise whereby the California National Guard allowed its facilities and equipment to appear in the movie and the Pentagon gave permission for servicemen to appear as extras on their own time.

No such compromise was ever worked out between the Pentagon and Francis Coppola, despite his half-hearted efforts to obtain assistance while in the Philippines. At no point did he consider revising his script to meet the military’s basic objections even though the change of “terminate” to “investigate” would undoubtedly have led to his receiving limited assistance. In one last, futile attempt to obtain help, Coppola telegrammed President Carter in February 1977, saying that the Pentagon “has done everything to stop me because of misunderstanding the original script which was only a starting point for me.”

The director described Apocalypse Now as “honest, mythical, pro-human and therefore pro-American.” To complete the film, Coppola explained, “I need some modicum of cooperation or entire government will appear ridiculous to America and world public.” Without amplifying how the government would appear ridiculous, he said that the film “tries its best to help America put Vietnam behind us, which we must do so we can go on to a positive future.”

Whether Apocalypse Now can purge the past in order to make a better future remains to be seen. Coppola has demonstrated an affinity for violence in his films. While in the Philippines he explained that he was willing to use violence to “scratch old wounds” in making a film about Vietnam because he was “cauterizing old wounds, trying to let people put the war behind them. You can never do that by forgetting it.” Yet he also said, “I can allow the film to be violent because I don’t consider it an anti-violent movie. If you want to make an anti-violent film, it cannot be violent. Showing the horrors of war with people being cut up and saying it will prevent violence is a lie. Violence breeds violence. If you put a lot of it on the screen, it makes people lust for violence.”

In any case, it is doubtful if Apocalypse Now or any film about Vietnam can help the American image be “pro-human and therefore pro-American.” No movie about Vietnam can delineate events that occurred there in terms of American good versus enemy evil as Hollywood could do in its films about earlier American wars. Vietnam films can depict individual bravery and perseverance in the face of a determined enemy and perhaps even capture the essence of combat, the unique excitement of challenging death in personal combat. But filmmakers cannot show the United States winning a glorious victory and making the world a safer place. If, as George C. Scott in Patton says, “Americans love a winner and will not tolerate a loser,” it remains to be seen whether audiences will go to a Vietnam War movie whatever its focus or quality.