History, Then and Now

A sort of documentary oratorio."

So Jean-Marie Straub characterized Not Reconciled (65), his and Danièle Huillet’s first feature, and that applies to all their films. An oratorio sets a story to music, with orchestra, choir, singers as characters, but no dramatic representation, no acted action. With or without music, Straub and Huillet have their stories not so much acted out as recited in a setting of images and sounds, the film equivalent of a musical setting. They hold back the dramatic illusion, the fiction of another world made present before our eyes and ears. They always start with a given text, something already fashioned, written or painted or composed, and handed down from the past. They stage it and have it performed in a way that keeps it at a distance, at a remove from the present, because they want us to recognize it as a document of its time, just as they want us to recognize its cinematic staging and performance as a document of a later time, and just as they want us to recognize our own situation as spectators at a still later time. In a film by Straub and Huillet at least three different times always come into play.

Their best-known film, The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (68), sets the story of Bach’s life with his second wife Anna Magdalena to his own music. Rather than the man in some dramatization of his character and activities, the music is the rightful protagonist. Sound recorded direct, grounded in a concrete environment, is a governing principle for Huillet and Straub. We watch musicians playing Bach and hear the actual sound of their playing, right then and there. At a concert they would bring the music into our environment, our here and now, but the film portrays their then and there with vivid distinctness and so prepares us for a larger leap of the historical imagination. Unlike a concert, it asks us to ponder the original ground of the music in the life and times of the man who composed it in 18th-century Germany. The musicians wear the wigs and costumes and play the instruments of Bach’s time in actual old churches and rooms; and Anna Magdalena’s narrated chronicle tells about family matters, personal difficulties, money problems, career setbacks, the strivings and frustrations of her husband’s job as a musician. The film conducts a dialogue between Bach as he survives in his music and Bach as he lived and worked, between enduringly beautiful music and the often worrying circumstances of its composition, between transcendent aesthetic experience and the constrictions of living in the world, between the autonomy of art and its embedment in history.

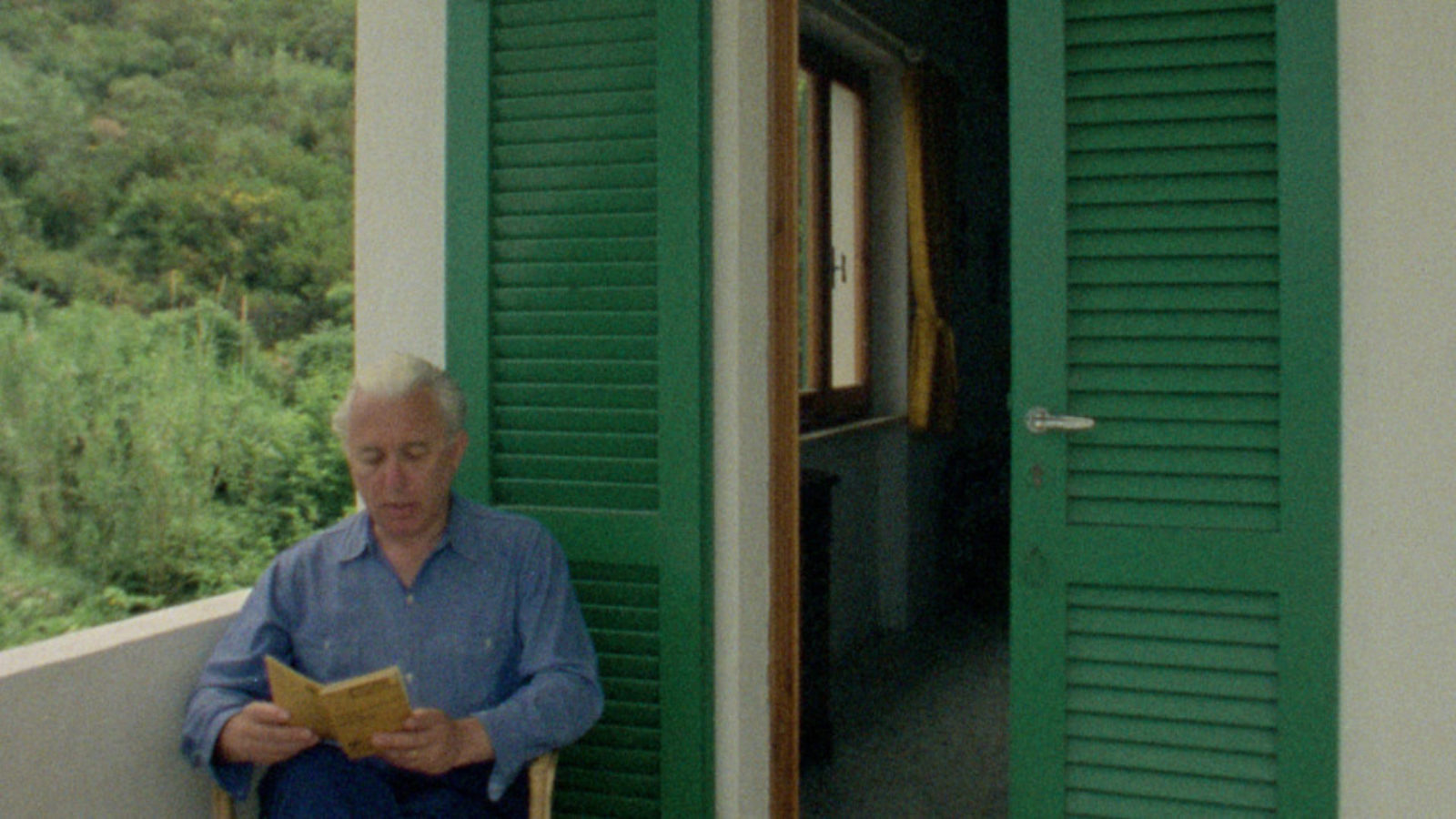

Fortini/Cani (76) centers on Franco Fortini, an Italian Communist of Jewish descent, and his book I Cani del Sinai (“The Dogs of Sinai”), a critique of Israel written right after its victory in the Six-Day War of 1967. Straub and Huillet could have interviewed Fortini and solicited his views at the time the film was made, but instead they have him read passages out loud from his book of 10 years before. Why? So as to compare two distinct moments in history, so that we may consider how words, like any other human expression, are motivated and understood in a concrete situation and circumstance. The Fortini who reads is not the same as the Fortini who wrote in direct response to the widely acclaimed Israeli triumph: in the film he enters into an implicit dialogue with himself. And that goes for the audience too: I for one am not today the same viewer who saw the film when it first came out.

A document of its time, of its author and his times, I Cani del Sinai combines a polemic and a personal memoir, so that besides the reader and the writer we have the recollected Fortini who grew up in Florence during the years of Fascism. “It must have been my father who made me pause before that monument on the Lungarno,” Fortini reads over a shot of the monument—which commemorates patriots who gave their lives for the cause of Italian liberation in the 19th century—and the camera, in a gesture that evokes the movement of someone’s attention, turns toward the base, where we see the mark of a triangle inscribed in the stone step: “and later I noticed in the stone the trace left by a Masonic triangle which the Fascists had torn out.” The mark left in the stone by that triangle, the memory in Fortini’s mind of his younger self before that monument, the written account of that memory, the sound of his voice reading that passage, the image on the screen of that triangular dent still there: all these signs of that missing triangle, in various contexts and with various connotations, are at this point brought together to our notice. The signs of the past are seen to take on a new meaning in each new situation, including our own as spectators invited to make our own connections.

History Lessons (Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, 1972)

What is past, asks Heidegger in Being and Time, about things from the past? Surely not the things themselves, since we encounter them in the present. If they are no longer what they once were, it is not because they are past but because their world is past. It is their world that is past—the whole of which they were part, the context in which they existed. A film is a piecing together. The pieces may come from different places and different times, but arranged into a whole they will be seen as parts of that whole, things in the world the film constructs on the screen. The context the film gives them, the whole of which it makes them part, the fictional world it brings into being, takes over. A film by Straub and Huillet is not put together that way. No such fiction is constructed, no such whole that wholly takes over, no such world whose coming into being erases what has been. The details captured by Straub and Huillet’s camera and microphone are not turned into what is but remain what has been, are to be recognized as things from the past, parts of different wholes, different worlds that no longer are.

Fortini’s father had spoken out against Fascism at the time of its coming to power in the 1920s, had been beaten and arrested, but later he hoped the Fascists would forget about that past and he signed up his son in their youth organization, the “Avanguardisti,” at whose gatherings the boy would see the two sons of his father’s old partner, the lawyer Consolo, who on an October night in 1925 had been killed by the Blackshirts right in his home, in front of his children. As we hear Fortini’s voice recounting this on the soundtrack, we see the Florentine Via dei Servi on the screen. We are not told, but perhaps it was here that the lawyer Consolo was killed, or here that the Avanguardisti gatherings took place, or here that Fortini’s family lived on the floor above Consolo’s widow and children but did not visit them, out of prudence. Our view begins above eye level, at the street sign on the rusticated wall over a corner bar, then pans along the façades until a perspective opens down the street and our eyes can travel into the depth; but at the far end of the street the huge dome of the cathedral brings the perspective to a halt, and the camera now tilts down to eye level and holds the view of the street and its traffic and passersby. If the dome looms large in back, the iron bars of a window now loom large in front, armoring the privacy of a house; if the dome (built by Brunelleschi, inventor of Renaissance perspective) is what we cannot see beyond, the limit of our perspective on public things, the window is what we cannot see into, the limit of our perspective on personal things. We are not told, but perhaps it was here: the story of what happened in the past, what may have happened here, hovers over the present but does not take over, does not appropriate this street as the site of that past. The street keeps its autonomy from the story yet the story resonates in the street, resonates as a possible context for these details we have before us, these parts without a whole, these things without a world.

In its specifics and its generalizations, its personal details and its political concerns, its movement from the Jewish boy in Fascist Florence to the more recent past of the Middle East, from Israel as potential mediator between the West and the Third World to Israel as complicit with the global interests of capitalism and imperialism, Fortini’s text covers a great deal: too much for us to assimilate in one hearing. It is characteristic of Straub and Huillet to put us deliberately in the position of not catching everything. They adapted History Lessons (72) from Brecht’s unfinished novel The Business Affairs of Mr. Julius Caesar, and the critic Colin MacCabe complained that “to understand History Lessons you have to know the Brecht novel and the Roman history independently of the film.” When I first saw History Lessons, I hadn’t even heard of the Brecht novel, and what I knew of Roman history I had learned in high school. Nevertheless I was gripped. People around me were walking out (as happens at the New York Film Festival with some of the best films), and I certainly didn’t understand everything, but I understood enough to be gripped. No one would dispute that Straub and Huillet’s films are difficult, but it seems to me that what people find most difficult is giving up the notion that they have to understand everything. Politics is an area in which people have strong opinions about things they don’t know enough about, and it serves a useful political purpose just to make us aware of all that we don’t know.

A married couple who made films together for more than four decades until her death in 2006, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub pursued a solitary path in their art. Both of them were born in France (Straub in Lorraine, on the border with Germany), and they might have been associated with the nouvelle vague had they not moved to Germany so that Straub could avoid being drafted into the French army at the time of the Algerian War. Their films speak German, French, and Italian—always the language, the wording of the original work. Their adaptations include a short story by Heinrich Böll in Machorka-Muff (63) and his novel Billiards at Half Past Nine in Not Reconciled, a Corneille tragedy in Othon (70), a Schönberg opera in Moses and Aaron (75) and another in From Today Until Tomorrow (97); Pavese’s Dialogues with Leucò and The Moon and the Bonfires in From the Cloud to the Resistance (79), Kafka’s Amerika in Class Relations (84), two versions of a Hölderlin play in The Death of Empedocles (87) and Black Sin (90), and his and Brecht’s translation of Sophocles in Antigone (92); Cézanne’s reported observations in Cézanne (90) and A Visit to the Louvre (04), the Sicilian novels of Elio Vittorini in Sicily! (99), Workers, Peasants (01), The Return of the Prodigal Son (03), and The Humiliated (03). The mythic conversations in Pavese’s Dialogues with Leucò have also served as the basis for Quei loro incontri (“Those Meetings of Theirs,” 06), one of Huillet and Straub’s last films together, Artemis’ Knee (08)—his first film after her death—and some of his others since.

To put the camera on tracks that are not part of the scene represented is to treat it as a fictional observer. Straub and Huillet prefer to treat it as an actual observer. Their camera at times tracks on its own, but only for a short distance. In their extended traveling shots they have it accompany a character’s movement or put it in a moving vehicle—such as the oxcart where Oedipus and Tiresias ride together and talk in From the Cloud to the Resistance or the car a young man drives around the streets of Rome for long stretches in History Lessons. Thus they ground the moving camera in the scene. They see no need for that, however, in their distinctive panning shots. These proceed at a deliberate, contemplative pace and yet keep surprising us by bringing things near and far unexpectedly into view. And the camera has a way of retracing its steps, reversing direction or going full circle and continuing over already covered ground: things it has gone past mustn’t be forgotten but examined anew. In Fortini/Cani the panning camera takes a series of prolonged looks around places in the Apuan Alps where the Nazis massacred Italian partisans, places shown almost entirely without people: we are to bear in mind the past and think about the future of the human beings living there. Such lingering, depopulated panning shots mostly make up the short Lothringen! (“Lorraine!,” 94), which looks around Straub’s hometown of Metz, the setting for a historical reflection on the attempt by the Germans to impose their ways on Lorraine after the Franco-Prussian War. Panning, especially as Straub and Huillet do it, is a more material, more grounded movement than tracking.

History Lessons (Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, 1972)

The movement, the framing, the editing of Straub and Huillet’s images always seems peculiar and at the same time purposeful, odd and at the same time precisely calculated. Their shots are often off-center, as when the young man in History Lessons, sitting in a garden and listening to a banker from ancient Rome who tells him the inside story of the business deals behind Caesar’s military campaigns, is last shown on the lower right of the screen, an image mainly taken up by surrounding hydrangeas stirred in the wind. On his face we may discern a growing anger at the banker and at Caesar’s profitable exploits, but he says nothing, and we are not simply to base our response on his as in a conventional reaction shot. Huillet and Straub’s formal oddities and idiosyncrasies invite our own response. We look at these wind-blown pretty flowers in a rich man’s garden and wonder what to make of them. Does their agitated beauty represent privilege to be blown away? Or does it represent the winds of change, the energies of nascent revolution? It is the beauty of art stirring us into thought.

So as to give us pause, to have us ponder the look and meaning of things, Straub and Huillet have their shots go on longer, often much longer, than usual. But they cut sharply and on occasion quickly. At one point in From the Cloud to the Resistance, the protagonist, who has returned for a visit to his native Tuscany after the Second World War, sits alone at a table while several persons stand at the bar and denigrate the partisans and Communists who fought against Fascism. We see these persons one by one; we don’t see the protagonist but hear his words over a black screen as he speaks in defense of the partisans. A man at the bar says the Communists are all murderers, and now we see the protagonist as he expresses disagreement—whereupon, for a sudden instant, we cut to a reverse angle of the whole group at the bar, then back to the protagonist, then again an abrupt brief shot of the group that feels like a hit at them, then back again to him as he rises from his table, pays for his drink, and leaves. A powerfully rendered shot-reverse-shot confrontation between an individual and a group: Straub and Huillet may frequently draw things out, but they well know the impact of cutting things short.

They have been compared to Robert Bresson, who famously disdained theater and called his actors “models” because he didn’t want them to act. But Straub and Huillet, while close to documentary, are seldom far from theater, whether they adapt plays or operas or turn written pages into talkative scenes. Though they keep dramatic enactment in check, their cinematic oratorios are even so a kind of theater performed by actors who may lend their speech unaccustomed inflections but still inflect it, may not act naturalistically but still act. Sicily!, for example, is forcefully acted in a mode verging on the operatic and at the same time rooted in material reality. On the screen Straub and Huillet manage to stage texts unsuitable to current theatrical practice or never meant for theater in the first place.

They could be compared to Ozu in the weight they give to scenes of conversation and the way they deploy shots and reverse shots in notable departure from the norm. Except that Ozu arranges his own regular patterns, disregards convention and sets up his own alternative system of shot/reverse shot, whereas Straub and Huillet take an approach more irregular, more about breaking patterns, disrupting expectations. History Lessons is something of an essay in the shot/reverse shot and its expressive variances and anomalies: look at the young man’s conversation with a peasant as opposed to the two he conducts with the banker. Or look at the opening scene of Sicily!. The Sicilianborn protagonist, returning for a visit after many years away, is shown with his back to us, by the Messina harbor, as we cut between him and his interlocutor, a farmhand who despairs of getting his wages in oranges that nobody seems to want. A strange sort of shot/reverse shot, disallowing the usual mediatory alignment with each character in turn, declining to put a face on a protagonist silhouetted against the water like an arriving question mark. A strange start to a strange journey we share with him without exactly sharing his point of view on those he encounters. He is, in the source novel—Vittorini’s Conversations in Sicily—the first-person narrator, but here he just talks to others who are themselves first persons with their own claims on our attention.

For all the distance, the reflective detachment—the Brechtian alienation, if you wish—that Straub and Huillet induce, their films engage our feelings and can move us deeply as Sicily! does. With his mother, a self-possessed woman of peasant stock, the protagonist has a lengthy talk whose formality touched with affection perfectly catches the quality of a reunion between a mother and a son who left home long ago. She has a herring on the fire when he arrives at the house where she lives alone, and they talk about food and about the past, about the father she reveres and the husband she disparages, about the wayfarer who seems to have been the love of her life. Her speech is fluent and stately, but she grows pensive, introspective, as she recounts how the wayfarer, who found work at a sulfur mine in the region, abruptly stopped coming to see her, and she thinks he was killed that winter when a mining strike and a peasant rebellion were suppressed. With heartbreaking pauses she asks why else he wouldn’t have come again.

The final conversation takes place in a village square where the protagonist meets a knife grinder who declares that nobody in this or any other village gives him knives or scissors to sharpen. So implausible a statement can only be taken metaphorically. In Vittorini’s novel, written in the late 1930s under Fascist rule, it surely alluded to the sharpening of weapons for fighting Fascism. Straub and Huillet update the metaphor, or rather, ask us to compare what it meant then and what it can mean now. They started making films at a time when it seemed possible to change the world, to sharpen weapons against, as the knife grinder puts it, those who offend the world. Faithful through the passing years to that revolutionary aspiration, Straub and Huillet bring their film to a stirring close with the protagonist’s hopeful newfound solidarity with the knife grinder.

Gilberto Perez (1943-2015) held the Noble Chair in Art and Cultural History at Sarah Lawrence and is the author of The Material Ghost: Film and Their Medium and the forthcoming The Eloquent Screen: A Rhetoric of Film.