Head Wide Open: Being John Malkovich

Being John Malkovich, the debut feature from Spike Jonze, is as paradoxically cerebral and patently ridiculous as its title implies. Jonze, a director who cut his teeth on the world of music video and TV commercials (is there a distinction?), is an artist who revels in the cult of offbeat aura. He also brings to each of his projects an unmistakable love for the visually illogical. What one becomes acutely aware of when watching his commercial showreel is a truly subversive mind working away, anonymously, within the most massive of mass media: television.

Connoisseurs of commercial detritus have probably seen—dozens of times—the Jonze Nike ad in which Pete Sampras and Andre Agassi commandeer an urban intersection for an impromptu tennis match, only to have the proceedings end when a city bus plows through their net. And then there’s the Levi’s ad Jonze chose to shoot in the hustle and bustle of an emergency room. A badly mangled accident victim is wheeled in. The beeping of the medical monitoring equipment strikes a chord in his memory, he pulls off his breathing mask, and then within moments he and the hospital staff are performing group karaoke to the Eighties dance hit “Tainted Love.” The patient goes into cardiac arrest, electroshock paddles are applied to his chest, and the doctors peer anxiously into his face for a reaction. The beeping resumes with, of course, more joyful singing and dancing. The end. (The audience may laugh; but are they aware the director has just equated a corporation with a state of mind?)

The freedom to be illogical, to put the wrong things in places where they somehow become more than right, is one of the beauties of the music video/TV commercial idiom. With Being John Malkovich, Jonze has found the perfect material, provided by first-time screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, to extend the delirium to feature length. And what, pray tell, is he placing where? Why, other minds into the head of John Malkovich. (The title, as it were, is more than literal.)

The story begins with a down-and-out puppeteer named Craig Schwartz (John Cusack). Schwartz lives with his animal-collecting wife Lotte (Cameron Diaz) and desperately needs to find a way to supplement his zero-income passion for puppetry. In a telling exposition of what it is that makes Schwartz tick, we see him perform with his puppets on a sidewalk. A young girl stops to watch as the puppeteer recreates the 12th century tale of Abelard and Heloise. It’s a canny choice for a film that deals, on one level, with the endless circular angst of sexual frustration. (Abelard, as we all recall, was castrated.) The puppets, separated monastically by the walls of their cells, writhe in freeform communication—an air-guitar dry hump of ecstasy. As soon as the girl’s father realizes what it is his daughter is watching, Schwartz gets a fist in his face. True art transgresses the pedestrian; and the pedestrian strikes back.

When the bruised Schwartz applies for a filing job, the audience is given the first hardcore indication that this will be a film governed by its own internal laws. Staring at an elevator panel, Schwartz is dismayed to discover there is no button for the 7 1/2th floor. A veteran elevator rider comes to his aid by pausing the elevator between floors and then prying the door open for Schwartz with a crowbar. The 7 1/2th floor is, indeed, a half floor. The ceilings are unnaturally low; people move cautiously about, bent over in compensation. The receptionist (Mary Kay Place) claims to not understand a word Schwartz is saying, the boss (Orson Bean) excuses his own nonexistent speech impediment, and everything begins to settle sideways.

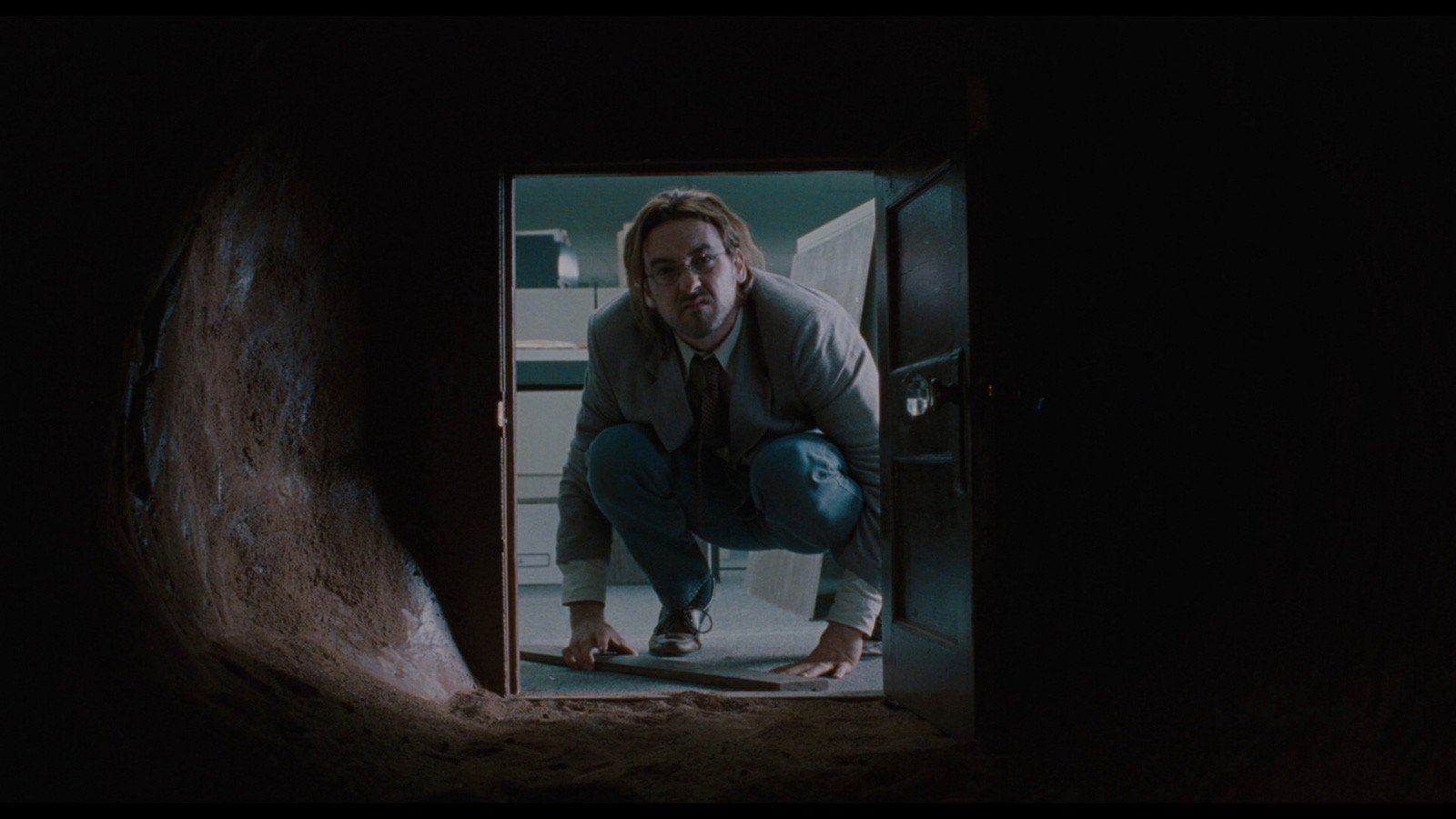

When Schwartz accidentally discovers a hidden passageway behind a large filing cabinet, things go completely Borgesian. As curiosity draws him into the tunnel, an invisible force takes hold and he is vortexed into the head of a strange man inhabiting unfamiliar surroundings. Checking his teeth in a mirror, Schwartz is dumbfounded to discover he is inside the head of John Malkovich. (Yes. The real John Malkovich.) After about fifteen minutes of unintentional personality osmosis, he falls from the sky to land by the side of the road somewhere off the New Jersey Turnpike. After a little practice it all seems perfectly normal.

Being John Malkovich utilizes a surreal persona transferral technique to address, among other things, problems of displaced desire. Schwartz and his wife Lotte have both become smitten with a mysterious woman who also works on the 7 1/2th floor. Maxine (Catherine Keener) comes up with the idea to utilize the Malkovich portal as a cash cow. Soon, an after-hours enterprise is providing seedy clients with access to the head of the movie star. Meanwhile, to up the ante on absurdity, Schwartz and Lotte vie for the sexual charms of Maxine by taking turns inhabiting Malkovich while he is engaged in amorous activity with her. It sounds convoluted, but it is only the tip of a labyrinthine iceberg. Just wait and see what happens when Malkovich, who is greatly disturbed when he discovers he is being metaphysically exploited, demands entrance into the tunnel—and his own head.

The beauty of the film is the way it elevates John Malkovich from an actor to an axiom. It immediately begs the question: Out of all the possible subjects that could have been placed in the title role, why Malkovich? The choice is as perfect as it is ineffable. Malkovich has made a career out of an unnerving balance between quasi-reprehensibleness and enigmatic sexual attraction. To open up and accept him in a role as charismatic sex object is not unlike the feeling of sexual surrender itself. Even with all his soft, undefinable formlessness, he can always manage to permeate the air with coarse, unmitigated allure. The critic David Thomson tried to deal with the dilemma in his Biographical Dictionary of Film: “Yet is there more than a handful (at the level of audience) that wants to see him—let alone in leading romantic roles? There is no hiding his strangeness—gangling frame, thick legs, receding hair, buttony eyes, blank look, hallucinated voice … to all of which Malkovich brings a deliberate, nearly insolent, affectlessness. He does not seem quite normal or wholesome—he can easily take on the aura of disturbance or unqualified nastiness. So it is all the more remarkable that, by the age of 40, he does stay within the reach of being a lead actor.”

Remarkable indeed. But there you have it. And obviously, in this case, what remains most interesting is not so much the concept of an audience that wants to see him, but the existence of a writer and director collaborating to place him in a role where all of the aforementioned antithetical forces come into such strong play. The bottom line, in the film’s version of reality, is that Malkovich is neither more nor less than any of the anonymous humans that pass through life without the benefit of limelit incandesence. We are just too blinded by the stars to realize it. In one sequence, Schwartz peers through the eyes of Malkovich as he fishes around in his refrigerator for leftover Chinese food while carrying on a discussion about various bathroom towel characteristics with a telephone salesperson. People will pay money for this? There is something enlightening going on here? Of course. But what? Theodor Adorno, one of the wettest blankets in the entire history of cultural analysis, warned many years ago of the dangers inherent in film realism. Imagination and reflection, in Adorno’s unhappy world, are trampled underfoot by popular films that appear to be extensions of our own miserable reality. Being John Malkovich toys with Adorno’s critique and then moves on to bigger fish. So what if John Malkovich is just like the rest of us? Spike Jonze is not content with a mere exposé of the vapidity of the entertainment industry or the callowness of the cult of personality. (That would be sawing his own legs off.) That these things come to mind while watching the film is well and good, but the film willfully leaves the miasma of critical theory behind, which for it is more of a playground than a prison, and ends the story with an entirely different set of propositions. I won’t ruin the fun here. Suffice to say the film posits the concept of Being John Malkovich as an entry point to the eternal. Now if Adorno were alive today, I think that’s something he may have been able to sink his overly suspicious teeth into. And Malkovich? He must love it to death.