Although he made one movie about mad love—The Curious Case of Benjamin Button—David Fincher never seemed a director deeply concerned with intimate relationships between women and men. His primary subject has been masculinity as a struggle within the male psyche (Fight Club, The Social Network) or against a savage doppelgänger (Se7en, Zodiac). What links these films to his wildly anticipated Gone Girl is his tragicomic sense of the absurd, as it applies to the extreme acts human beings commit in order to protect and project an image of self largely based in what old-fashioned existentialists termed false consciousness.

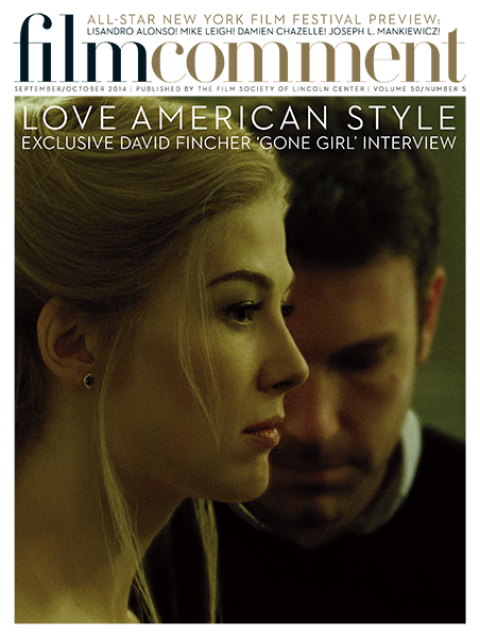

Adapted for the screen by Gillian Flynn from her 2012 bestseller, Gone Girl has engendered much speculation, especially among the novel’s six-million-plus readers. Indeed, no major film since Hitchcock’s Psycho has been such a minefield of spoilers, and for viewers who haven’t read the novel, that minefield begins less than halfway into the narrative. We have tried not to give any of the film’s surprises away. Gone Girl is about Amy and Nick Dunn, two not particularly distinguished journalists who met and married in New York just before the crash of 2008 cost them their jobs. They move to the small Missouri town where Nick grew up and which Amy, a New Yorker born and bred, finds intolerable. When Amy goes missing, Nick becomes the prime suspect in the investigation of her possible murder.

How did you go about adapting Gone Girl?

The book is many things. You have to choose which aspect you want to make a movie from. Most interesting to me was the idea of our collective narcissism as it relates to coupling, or who we show to our would-be mates and who they show to us. It’s the most absurdly honest part of the book and the newest thing in terms of what it illuminates about marriage and what may or not be going on behind closed doors.

Let’s talk about the casting. Rosamund Pike is fabulous and exactly on the nose in terms of who I think Amy is. But the casting of Ben Affleck as Nick is a bit more surprising. Usually you work with actors who have great technical flexibility. It never struck me that Affleck is skilled in that way.

He’s probably a lot craftier than you give him credit for. He’s wise as an individual, extremely bright, and he’s very attuned to story and where one is in the narrative. I enjoyed working with him immensely. The baggage he comes with is most useful to this movie. I was interested in him primarily because I needed someone who understood the stakes of the kind of public scrutiny that Nick is subjected to and the absurdity of trying to resist public opinion. Ben knows that, not conceptually, but by experience. When I first met with him, I said this is about a guy who gets his nuts in a vise in reel one and then the movie continues to tighten that vise for the next eight reels. And he was ready to play. It’s an easy thing for someone to say, “Yeah, yeah, I’d love to be a part of that,” and then, on a daily basis, to ask: “Really? Do I have to be that foolish? Do I have to step in it up to my knees?” Actors don’t like to be made the brunt of the joke. They go into acting to avoid that. Unlike comics, who are used to going face first into the ground. Nick is someone who has skated by on charm and has that as a deflection mechanism. And that’s what crucifies him. And Ben got that. When I first met with him, we didn’t have the script yet, but he’d read the book. I mentioned a National Lampoon record from the mid-Seventies called That’s Not Funny, That’s Sick. That’s kind of the tone of the movie. If we play it too earnest and sincere, then it’s tragedy, but if we go with the absurdity of it, I think it can walk a satirical line.

The movie keeps changing on you as you watch it.

I can’t wait to see what will go on between couples at dinner after they see the movie. There are so many interesting tectonic shifts. When the people I’ve shown the movie come out of it, they are either Team Amy or Team Nick. Team Amy doesn’t have a single quibble about her behavior, and Team Nick doesn’t have any problems with his. Then there are people who primarily measure it against the book and how they felt about the characters in the book. And the narrative of the movie is vastly denuded from the way it’s allowed to grow and bloom in the novel. It wasn’t a defoliation as much as a deforestation. Once you got it back to the branches and the trunk, it was pretty easy to see that this movie was going to be about who we are and who we present to those we are endeavoring to seduce. And the absurdity of that difference needed to be part of the two-and-a-half-hour fabric in a much bigger way than in the novel. For me, the 30 percent of the novel that’s about who we present—our narcissistic façades—becomes the entire foundation of the movie.

When we started working together, the biggest concern was how we would represent the two voices. Gillian [Flynn] quickly adapted to the structure that the “she said” is in flashback and the “he said” is being lived out in front of you. And you question which one is reliable or if either of them are. When we pruned back, Amy’s “cool girl” speech becomes central to the exploration of “we’ve been married five years now and I can’t get it up any more to be that person you were initially attracted to and I’m exhausted by it and I’m resentful that you still expect this.” And you throw in a little homicidal rage and it’s a fairly combustible idea. Does that make sense? [Much laughter] I’m so sorry I made this movie: it’s just not marketable.

Read an expanded version of the interview here, or purchase a digital or print copy of the issue.