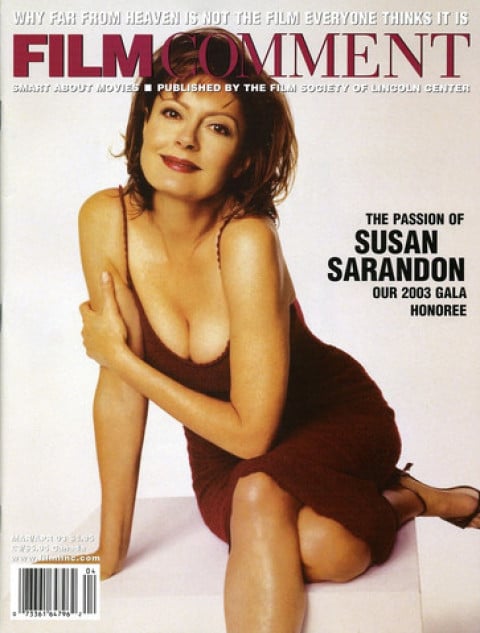

Haynes and Sirk

Why, for some of us at least, does Todd Haynes’s Far From Heaven seem so far from Douglas Sirk?

That’s not what the reviewers promised us. Take this early rave by the New Yorker’s Anthony Lane:

“Everything from the crane shots to the genteel fades … shows a director hitting a new high in pastiche, and, if you are a film buff, Far From Heaven will be an all-body massage; notable moans of delight will come from fans of Douglas Sirk, who made Imitation of Life and Written on the Wind, and Max Ophüls’s The Reckless Moment, from which Haynes borrowed the character of the supportive black maid . . . .”

Never mind the tone of this, coming from a reviewer who often manages to sound both pompous and antic in the same breath: it names the right precedents—Ophüls’s American masterpiece and Sirk’s two greatest films. Though it curiously fails to mention the Sirk film that Haynes is most closely imitating, 1955’s All That Heaven Allows, starring Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson.

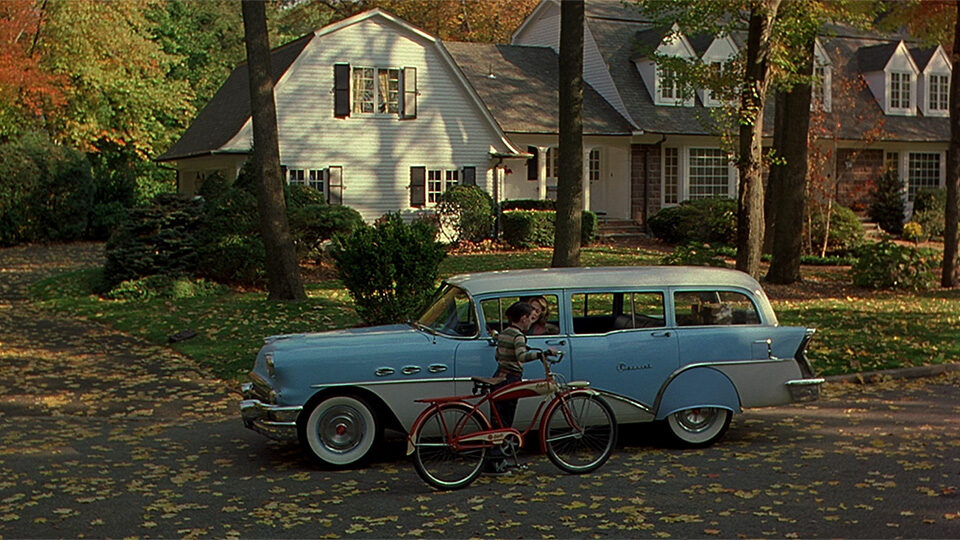

Far From Heaven reproduces not only those crane shots and slow fades from the Sirk film but also its Populuxe interiors, its golden-leaved garden belonging to the heroine with two children (grown to full awfulness in the Sirk film, still minors in the Haynes, as in the Ophüls), and its central story of a woman beset by the prejudices of her upscale suburban town and involved in a near-scandalous love affair. Quite a bit less than scandalous in the Haynes film (since there is no lovemaking) but quite a bit more too: the romantic object of desire is black. And where the Jane Wyman heroine is a widow, Julianne Moore’s husband in Far From Heaven—Dennis Quaid—is not only alive and in residence as head of the house and family, but gay, though struggling with it. Throughout, it’s this latter topic, along with the interracial one, that gives Haynes’s film a feeling of substance, of social reality, lacking in the Sirk film, in which the heroine’s problem was that her lover was a gardener (!) and that her children, as well as the town, were snots about it.

All That Heaven Allows is not a major Sirk film—it doesn’t compare to the wonderful, even more bitter family melodrama he made just after it, There’s Always Tomorrow (56) with Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray, or even to his earlier film with Stanwyck, All I Desire (53), about a tum-of-the-century small town. Haynes is imitating a movie that he can certainly improve upon—and he does. The character of the heroine’s nasty-sweet best friend, for example, played by Patricia Clarkson (Agnes Moorehead in the original) is written and performed with perfect tonal control and accuracy. And some of the movie’s domestic scenes with Quaid’s suffering father and husband, his self-pitying bitchiness intruding on the ghastly little charades of family happiness, are authentically upsetting.

Sirk had a varied career in Hollywood, ranging from the offbeat independent productions he did in the late Forties—some of them, like Lured (47), Sleep My Love (48), and The First Legion (51), quite marvelous—to the glossy big-studio assignments he got at Universal, where he became more or less house director and where he made, by almost any measure, more bad movies (like Interlude (57), Sign of the Pagan (55), and 1957’s truly execrable Battle Hymn) than good ones. But it was here that he did his major work. Which has a character, it seems to me, quite opposite to anything suggested by Haynes’s homage—“hitting a new high in pastiche”—or by the critics who’ve been kvelling over it.

Sirk’s great films are about people who don’t believe in death, made by someone who does. That is the explicit contrast between the black characters and the white ones in Imitation of Life (59), and the implicit one between the “bad” and the good couples in Written on the Wind; What could be more alien to that than the sort of tasteful heart-tugging you find in Far From Heaven? Like the ending—as Julianne Moore’s Cathy says goodbye to the man she loves but can never be with, as his train pulls away from the platform, as she drives off in her turquoise station wagon (the same color as the one in All That Heaven Allows), as the camera and the music rise. So it’s okay, that moment—the movie has earned that at least, you suppose—and the filmmaker has let you know (has he ever!) that he knows how cliché this all is, so you can relax and enjoy it guilt-free if you want. But then think of what Sirk does for a contrast—Annie’s funeral at the end of Imitation of Life, Marylee’s totentanz at the climax of Written on the Wind. Haynes means to make you cry, as he’s said in interviews. Sirk’s great films mean to wipe you out.

Purchase the March/April 2003 issue of FILM COMMENT to continue reading.