George Harrison sits quietly amid the bustle at Warner Bros. Records in Burbank. The staff around him is busily promoting Cloud Nine, the ex-Beatle’s first solo album in five years and, just certified platinum, his biggest hit since the early Seventies—but George is talking film. His HandMade Films, co-founded in 1978 with American business manager Denis O’Brien, has made him a movie mogul of sufficient stature to have received the annual award for contributions to the British film industry from London’s Evening Standard last year. In a country in which film production companies have been dropping like flies, HandMade is, hands down, the most prolific of the bunch—virtually the only one able to finance big budgets without outside help.

Though Harrison is determined to keep his London-based company small and British to the core, a trans-Atlantic invasion is evidently in the works. HandMade set up an office in New York last September and released its first U.S. film, Five Corners, in January. Of the 10 projects underway this year, seven will be American. Quite a leap from the early days of Monty Python’s Life of Brian and Time Bandits, irreverent low-budget comedies that channeled enough revenues into the company coffers to finance such films as The Long Good Friday, Mona Lisa, and Withnail and I.

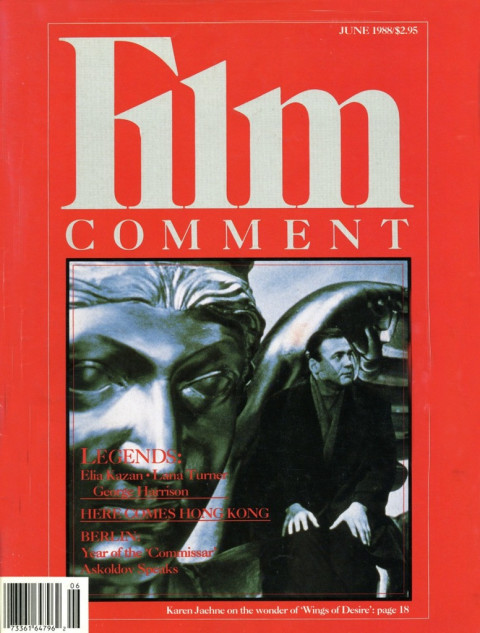

Success doesn’t seem to have taken much of a toll on Harrison, now 45. He’s a likable man, gentle and unassuming—less a legend, in his mind at least, than a fellow who’s grateful to have landed on his feet after the dissolution of an early marriage, years of legal and financial wrangles, and a spotty solo recording career. Remarried since 1978 to Olivia Arias, a secretary at his Dark Horse label, and the father of 9-year-old Dhani, Harrison seems to have found the serenity that eluded him early on. The three live in a palatial Victorian mansion on 30 acres outside of London, a spot where George hangs out with his mates and indulges his passion for gardening. Lest anyone confuse him with a traditional country squire, however, he still sports a scruffy beard and arrives for the interview in a one-of-a-kind cranberry jacket imprinted with eros and erotic. Breaking years of self-imposed silence, the quiet Beatle finally sounds off, talking about the ups and down of moviemaking, the challenges ahead, and the newfound balance in his life.

You co-starred in three films as a Beatle. Now you’ve surfaced on the other side of the camera. How did it happen?

Purely by accident. An English company had backed out of the Monty Python film Life of Brian in preproduction. And the guys, friends of mine, asked me whether I could think of a way to help them get the film made. I asked Denis O’Brien, who had been my business manager since the end of ’73. After thinking about it for a week, he came back and suggested that we produce it. I let out a laugh because one of my favorite films is The Producers, and here we were about to become Bialystock and Bloom. Neither of us had any previous thought of going into the movie business, though Denis had a taste of it managing Peter Sellers and negotiating some of the later Pink Panthers films. It was a bit risky, I guess, totally stepping out of line for me, but as a big fan of Monty Python my main motive was to see the film get made.

When did you realize this was going to be more than a one-shot venture?

Denis got a bug for it. And the pythons as individuals were all writing scripts. Terry Gilliam presented us with this brilliant idea, which turned into Time Bandits. Michael Palin had done a BBC-TV series, Ripping Yarns, a series of 30-minute films, and I once mentioned it to him that if he ever wanted to write a big Ripping Yarn it would be just great. So he did. He also made A Private Function, an hysterical little Alan Bennett film that did really well in England. I don’t know why it didn’t take off in the U.S. Maybe we should rerelease it now. Anyhow, one thing led to another, and our films just kept happening.

After spending your life as a performer, does it feel strange to be wearing another hat?

In a way. When I was acting, there was always the feeling that the artists were the clever ones who do everything—and then there were these horrible people who put the money up and don’t know anything. Everyone subscribed to that old Hollywood myth that Executive producers hate everything and chop everything up after you’ve done it. When they’d walk into a studio, it would be, “Look out, lads, here comes ‘The Money,’ ” with everybody cringing at those fat cats. So it is sort of funny being a simple musician who’s now a producer or—inverted commas—“The Money.” I can see it from both sides. It’s nice to let people have as much artistic freedom as possible, but I’m the one who has to pay back the bank. If they want total freedom, they have to get their own money and make their own films. It has to be a give and take. But I think we’re quite reasonable.

Does film now take precedence over music in your professional life?

Fortunately, I haven’t has to choose. Last year I spent most of my time doing the record. Once I committed to it, I went into the studio and spent all the time needed to get it done. HandMade Films now has a good, competent staff of about 35 people who seem to know what they’re doing. If filmmaking becomes a chore for me, I don’t want to do it. I can choose how involved I want to be, or I can step back away from it and separate. That way, I can enjoy it more. Going out and making business deals isn’t me. If I had to, I’d soon want to get rid of the entire company. Denis is the business person. He does that. I know all the projects we’re working on and who’s doing them, and I don’t have to be there. I’m not looking for an office job. I just pop in on films a couple times to see how things are going. I never intended to be David Puttnam.

Three films: The Missionary, The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne, Bellman and True. All very different from each other on the face of it. Is there a common thread?

With the exception of Shanghai Surprise, which was a big disaster—and the only expensive “Hollywood” kind of attitude project we got involved with—all of our films seem to be films nobody else will do. No one would go near Life of Brian. The Long Good Friday was a pickup that had been shelved by the owners. It was the same company, by the way, that had turned down Life of Brian. They wanted to cut it and put it on television, while we put it out in the form that the producers, actors, and director had visualized. It’s a great little British gangster movie. Critics said they hadn’t seen a performance as good since Edward G. Robinson. And it was true. Bob Hoskins was fabulous.

If Denis O’Brien handles most of the business affairs, do you take primary responsibility for the creative end?

There are so many scripts coming in now. And, personally, I hate reading them. But a guy on staff named Ray Cooper serves as my ears. He’s also a musician, a percussion-and-drums player for Elton John, and I know I can rely on his being sensitive to the artistic side of things. There’s always a conflict between the “business,” what people see as the brutal business aspect, and the “artistic” side. Since I’ve been an “artist”—make sure you put that in inverted commas—and have Ray there all the time, it eases the problem a bit. If a couple of people on the staff all happen to like the same screenplay, then copies go out and everybody reads them and decides whether we’ll do it or not. I suppose Denis and I have the final say, but it’s rather a committee system. It takes a number of people to like a script before the red light turns to amber.

Are you happy, on the whole, with the direction the company is taking?

There are certain things I don’t like that always crop up into films. I hate all the violence. I don’t mind a few explosions for a laugh, or when it’s “integral to the story.” But the whole Rambo situation, with films where people just want to see others getting their heads blown off, I hate that. What we’ve released isn’t necessarily a reflection of the films I’ve liked best, of course.

It’s a funny business. Some films we’ve developed for three, four, five years have still not seen the light of day. We’d set them up and the director would drop out. Then, when a new director the actors approve of is lined up, one of the stars has got to go and make his other movie. By the time we replace him, another guy is gone. That kind of situation you learn to live with. And then there are films like Pow Wow Highway, in post-production right now, that go Number One with a Bullet. It came through my mailbox just a couple of months ago, and we’re making it straightaway. Like I said, funny business.

Is it getting any easier these days?

Somewhat. With the first batch of films we made we had our own money absolutely on the line—all the bank loans—and it was very hard for Denis to get distribution deals. We may have even finished a movie only to find we couldn’t line up a distributor. Now we’ve got a little bit of charisma going for the company, enough success for people to think, “Well maybe they are serious,” and a lot of people who’ve worked on HandMade Films who’ve had an enjoyable time. All that has slowly built to the point where, on a business level, it’s become slightly easier for Denis, and it’s made us want to do more movies. From my point of view, expanding our production schedule is much riskier. But from his perspective, it’s easier to do a deal with someone to distribute ten movies than one. Much harder to do separate deals for each movie. We’re also able to get good directors and good actors now because our reputation is getting better all the time. Still, it’s sort of frightening when you start a movie and you see all the people you’re employing. It’s quite a big responsibility. If I was to think about that, I’d panic. I wouldn’t want to be involved. I have a sort of kamikaze side to me that is optimistic, and in some ways I have to trust Denis’ business sense and hope he’s not going to bankrupt me.

At this point, are you still putting your own money on the line?

I do put quite a lot into every film. But not like when we started with Time Bandits and Life of Brian. For our first film, we put our office building, my house, and all our bank accounts—like a pawn shop—into the hands of the bank that was going to loan us the money. It was lucky the film paid off. We paid back the loan and put anything left over into the next one. Out of 15 films, we’ve had only three failures—four if you count Shanghai. But Shanghai was a failure only from an artistic point of view. We didn’t lose any money, since enough time has elapsed for us to be able to negotiate a more secure kind of deal up front.

With more than $50 million invested in production right now, HandMade has obviously turned the corner. Just how solid are you?

We’re OK. Though, with all this money tied up, the cash flow does get a bit shaky. It’s a matter of timing, being able to avoid getting caught short. A few of our films brought us back more than we expected, which helped us to pay off the flops. Things have been handled well on the business side, managed on a shoestring. We’re very penny-pinching in a way, trying to adopt a sensible approach—not many free limos. And we try to edit the scripts so that we’re not shooting footage that’s going to end up on the floor. If we continue on our current path, we’re poised to make a few dollars somewhere down the road.

Why have other British film production companies had such a hard time managing to keep their heads above water?

Basically, because it’s hard to get the money. Goldcrest was the big one over here. But all you need is one film like Revolution to go that much over budget and fail, and it sort of wipes you out. We were fortunate that the deal Denis set up for Shanghai Surprise made sure that it didn’t do us in. My understanding is that the cost of the film was covered in all the distribution deals. Once we delivered the film, we got back enough money to cover the budget, so even if the film was a flop, we were OK. If that happened to us back in 1980 or ’81, we probably would have gone the same way as most of the others.

With a budget of more than $15 million and a temperamental, high-profile husband-and-wife team, Shanghai Surprise was a tremendous departure for you, financially and aesthetically. Why did you give it a go?

I was dubious from the first. I get afraid by things like that. And a lot of others at HandMade didn’t want to make that film. Denis himself was just a couple of days away from just shelving the whole thing when suddenly the producer informed us that Madonna and Sean had agreed to be in it. At that time, it sounded like a good idea. But when we went ahead with it, it proved to be very painful for most of the people involved—the technicians as much as anyone, because of the attitudes of the actors. It was like “Springtime for Hitler” in The Producers: we got the wrong actors, the wrong producer, the wrong director. Where… did… we… go… right??? It wasn’t easy, but I was determined not to let it get me depressed.

Cannon Films suffered a similar fate when it paid Stallone $12 million for Over the Top.

Sure. We have to keep tabs on our budgets and not get carried away thinking we’re big shots. Many companies, with some success behind them, move into big, posh air-conditioned offices that all interconnect with private bathrooms. You see them swarming around in these limousines. It’s “Sod’s Law”: Even if we made hundreds of millions of dollars, once we moved out of our tiny, overcrowded office in London and got into the Big Time, I’m sure the bottom would fall out. The answer is to be humble. That’s it. Be humble. It would be nice, I suppose, from a staff point of view, to have a bit more space—our own viewing theaters, cutting rooms, and sound studios. But for me, as an ex-Beatle, I’m not into that trip of being a big shot. I peaked early. I got all that out of my system in the Sixties.

Part of Disney’s current success is die to the stable of actors it has signed in what some see as a return to the old studio system. Are you making a conscious effort to do the same?

It’s not an out-and-out strategic move, though we have worked with the same people a number of times. Bob Hoskins, of course, is one of them. He was the main reason Mona Lisa was so successful.

We said, “He’s done good for us. We’ve all enjoyed him. Let’s let him direct his own film.” We take a little chance here and there, calculated risks, not only because he’s good but because he’s a joy to be with. His charm is that no matter how famous and popular he is, he’s so straight and down to earth. He makes the Seans and Madonnas look ridiculous. We’ve also had the pleasure of working with Michael Caine, Sean Connery—“name people” who go about doing their roles. They’re not as complicated. They’re very professional.

Have you written any of the HandMade scores?

I got really involved with the musical end of Shanghai. That was another reason why it was personally sad for me. I’d plugged so much of my own time into it. I worked with a guy who scored movies before, Michael Kamen, who’d done Brazil with Terry Gilliam. I worked with him because it’s too much for me to take on. I’m not going to write millions of violin parts, conducting orchestras. That’s not my idea of having fun. He’d do that kind of stuff, and I’d put in some funny little things that appeared. I also did a couple of songs for Water and one for Time Bandits.

Your first American productions, Five Corners, was released this past January, and the majority of your current projects bear the U.S. stamp. Is this part of a larger effort to get a foothold over here?

That isn’t my idea, but I think it could be Denis’s; he’s interested in broadening the base. I personally would not like to see HandMade Films turn into an American company in New York or Los Angeles. I like it being in a nice little office in England. When we named the company, it was going to be called British HandMade Films, but for some reason the government registrar or whoever’s responsible for company names wouldn’t let us call it “British.” I think you have to have lost millions and millions of pounds before they let you call it “British”—British Leyland, British Rail. Other than that, I can’t see why they’d turn us down. I like to have American actors and directors. We’re not closed to anything, really. But I wouldn’t like us to become some big swanky American company. At that point, I’d probably bail out.

But aren’t Denis O’Brien’s instincts on target? Isn’t the American market as important to the film business as it is to the recording industry?

Of course. To really make it, you have to have some success in America—in film and in records. You can sell all you like in England and France and Switzerland. But you need a big response in the American market to pay the bills, to pay back the money and make the thing work. The turning point for our company came in the last year or two, when some of the films we made strictly as slow-budget projects got accepted in America. Mona Lisa was one. Withnail and I was another—which came as something of a shock. I really enjoy the film personally, but thought there wasn’t a snowball’s chance of the American people getting this kind of humor. The jokes seem very English to me. I’m glad to say I was wrong about that.

We’ve always been told that Americans want things to happen crash! bang! wallop! and want a film to be paced quickly. You get so terrified when there’s actually dialogue going on and people have to use their brains and listen. We’ve tried to give people credit for wanting to see a film with some kind of plot, dialogue, depth, and were pleasantly surprised that there are Americans who don’t mind working a bit—particularly given all the competition these days. Someone told me that 170 films were released between last August and Christmas in America alone. A few years ago, you could put a film in a theater in the U.S. and let it build on word of mouth. Now if you put a film out on Friday and it hasn’t grossed a certain amount of money by Saturday night, it’s gone. It’s ruthless—even more ruthless than the record business.

What projects have you in the works?

We have a comedy called How to Get Ahead in Advertising, about a fellow who wakes up with this great boil on his head and it sort of takes on its own personality. We’re going to do Stephen Berkoff’s Kvetch. We have great hopes for TVP, a film with David Stewart of the Eurythmics, who also conceived it. It’s about a little planet in outer space where everything has gone under from too much machinery. It’s like a little children’s thing, brilliant ideas in which the characters are actually musical instruments. They all plug into each other and can play together. Basically animation, but there are some people in it as well. Because HandMade Films is this warm, little, friendly company, Dave as a musician can work better with us. Nicolas Roeg directed Track 29, a psychological thriller starring Theresa Russell and Gary Oldman and written by Dennis Potter, who wrote Pennies from Heaven. And there’s lots more besides that.

You’ve upped your U.S. release schedule from two in 1987 to six in ’88. Will we be seeing more and more from HandMade films each year?

I hope not. I don’t like to have too much going at the same time. Do you remember those cabaret acts in which people kept all these plates spinning on sticks? They’d start up a couple, add a few more, then have to run back and give the first one a twist. They’d get another couple going, run back to the second and third ones, until they had ten plates all spinning at the same time. The problem is, if you don’t watch out, they all go crashing on the floor. I want to be careful not to get too carried away.

Are you surprised that your “baby” has grown up so rapidly?

I am, yes. I just hope that Denis doesn’t turn out to be a madman…

You’re worried that he’s beginning to spin too many plates?

Not yet. The logistics of it all makes it very difficult to get all those movies going at the same time. These plates you’re trying to spin are big, heavy things, you know. It’s good that he’s going for it in some ways, though. I would have been content just to do Life of Brian and Time Bandits—much happier just doing comedies. But, then, if I was in charge of this company I don’t think it would have gone on as long or gone as far, really. I probably would have encouraged us to have made even crazier films than we’ve made. I know I wouldn’t have been as adventurous in some areas. But at the same time, I don’t want to get too adventurous. I like to be safe and sure, you know.

Any thoughts about the future?

Someday, I’d like to make a real silly comedy movie full of silly music. I don’t really fancy my chances of being a scriptwriter or an actor, bit I do have a lot of silly ideas in the back of my head. If we can make enough money so that it doesn’t matter if I blow a couple million on my own ideas, I’d like to follow some of them up. Maybe as my last fling, I’ll have this huge but very cheap flop with all my mates in it.

Establishing a post-Beatles existence can’t have been easy. How are things going for you these days?

On behalf of all the remaining ex-Beatles, I can say that the fact that we do have some brain cells left and a sense of humor is quite remarkable. I’ve had my ups and downs over the years, and now I’ve sort of leveled out. I’m feeling good. I don’t get too carried away or too down about anything. I distance myself from things like the serious business side of the film company, or else I’d crack. I spend plenty of time planting trees, things like that. I have a lot of good friends, good relationships, plenty of laughs. A lot of funny little diversions that keep things interesting.

It sounds good. But don’t you ever, even for a moment, miss all the excitement, the highs?

No. Then’s then, and now’s now. In the late Seventies, I just sort of phased myself out of the limelight. And then all the new generations come up. You get older and change your appearance, and they forget what you look like. I suppose, though, with a new record out, that I’m launching myself back into show business for a while.

Was that a conflict for you?

No. I enjoyed making the record, though I don’t like to be on TV and do the interviews necessary to promote it. There was a time when I actually hated all that. But now I’m reasonably well balanced about it all and understand in my own mind why I’m doing it. Unfortunately, it will make me a bit “famous” again. I don’t really like being famous. I suppose I still am, but I don’t really think of myself as a famous person. People will be picking up magazines that will have me in them for a bit—but just for a bit. Then I’ll go back to being retired again. Or at least putting all this on the back burner. I’ve managed to find a balance between show business and a kind of peacefulness. It feels very nice.