The Gingerbread Man

More than Boston Market or even Starbucks, the Nineties' most successful franchise seems to be the novels-cum-movies of lawyer-cum-literary superstar John Grisham. Just like a new location for a fast-food chain, a Hollywood studio can purchase the rights to one of Grisham's stories and have a pretty solid idea of what they're going to get. Grisham's bestsellers seem designed to present themselves as perfect fodder for the Hollywood hit factory. The first Grisham-based film, Sydney Pollack's The Firm, appeared in 1993; the release of Robert Altman's The Gingerbread Man in the early days of '98 brings the total to seven, with at least one more on the way, to the ka-ching of well over $500 million at the box office.

But set aside the bean-counting for the moment to consider something more intriguing. In a variation on the age-old auteur debates and the place of the “maverick” within the studio system, the Grisham films cast light on the state of authorship in contemporary Hollywood. These adaptations have attracted a fascinating cross-section of directors: older, studio-friendly craftsmen (Pollack and Alan J. Pakula), younger journeymen both renowned (Joel Schumacher) and unheralded (James Foley), and, lastly, two maverick directors renowned for following their muse and bringing us the greatest in film art—one more or less beaten into submission by the system (Francis Ford Coppola), the other remaining at arm's length from the studios with varying degrees of success (Robert Altman). Though these categorizations are shorthand—Pakula in particular seems caught between types—they're useful when discussing the Grisham films, which are less a genre in their own right than a cycle within the courtroom drama.

The “John Grisham films” pose several challenges to directorial authority. They demonstrate immense similarities with regards to structure, story, and character, even though Grisham himself does not receive screenwriting credit for any of them (although The Gingerbread Man is based on an apparently overhauled screenplay by Grisham). The bidding wars over his properties have certainly provided Grisham with the leverage to secure power of approval over the directors of his films. As with Stephen King, Grisham's authorial identification with these adaptations has grown so strong that the next-to-latest was officially titled John Grisham's The Rainmaker. On the other hand, the heavy reliance on starpower to fuel the Grisham vehicles not only suggests a lack of faith in their merits as pure storytelling, it may affect the balance of power: is The Firm a Tom Cruise film first and a Sydney Pollack film second?

The Firm

So where does this leave the director? Is there room for personal expression within the rigid confines of the story Grisham tells, over and over again? Oddly enough, yes. In fact, these films may be the ultimate test of directorial vision and authority. Just as the original auteur-oriented Cahiers critics imagined Hollywood directors sneaking in under the studio radar to make films that satisfied both audience expectations and their own sensibilities, the Grisham films, by presenting each director with the same basic materials, demand that much more from the individual director to make the film truly his.

To think of the Grisham cycle is to struggle to remember exactly which film a given scene or character comes from—the events and situations bleed together into some weird loop endlessly supplied with lawyers with accents and corporations and trials and chases. The template for the next Grisham franchise to pop up on the corner would be roughly this: young, earnest Southern lawyer, fresh out of law school, full of ideals and morals and good ole tenaciousness, tries to right some wrong. The bad guys always turn out to be not the government, the time-honored all-pervasive They (in fact, in The Pelican Brief, the CIA are made into guardian angels instead of weird spooks), but instead the new Them: Big Business. Rest assured that there is or has been a Big Cover-Up, after uncovering which the young lawyer finds BB's henchmen on his/her trail, experiences a dark night of the soul, and then a third act Big Trial/Big Chase where justice prevails. In the ideal Grisham formulation, the ending is an outlandishly unambiguous triumph of good guys over bad guys.

The Firm superficially resembles Pollack's earlier Three Days of the Condor, likewise a star-driven conspiracy story. However, where in the earlier film dread and paranoia became so all-pervasive for our hero that even the neighborhood postman could be a stone killer, in The Firm evil remains localized (when has a creepy albino character not been a hitman?), easy to identify, and therefore easier to fight. The Grisham cycle is the Nineties child of the paranoid conspiracy thrillers of the Seventies—spoiled, self-assured to the point of cocky, and always, always getting what it wants.

The Pelican Brief

Pollack isn't the only Grisham director associated with the now-revered paranoia films of the Seventies. Coppola made one of the best, The Conversation, and Pakula was in many ways the master of the genre—which is what makes his descent to a film like The Pelican Brief that much more disheartening. Pollack, at the very least, constructed a successful star vehicle for Cruise, whereas Pakula can't seem to decide whether to focus on Denzel Washington's investigative reporter (shades of Parallax View and All the President's Men) or Julia Roberts's idealistic Southern law student (pure Grisham). Pakula's “rehabilitation” into professional craftsman storyteller is exemplified by the shift in his visual style. In his prime, his compositions were always skewed, the characters literally squeezed out of the frame by their environment, always off-center and off-balance. In The Pelican Brief it's as if someone walked up and righted the camera: the compositions are more balanced; the actors occupy the dominant space in the frame. There are, however, several visually arresting moments even here: During a scene that calls for Washington to stonewall an administrator so that Roberts can sneak by, Pakula shoots Washington through a heavily foregrounded doorway, so that he seems to be talking to a wall that is simultaneously jutting out towards the audience; after Washington exits the open portion of the frame, the administrator steps into it, giving a rather unconvincingly cheery salutation. Here is a brief spark of Pakula's former mastery, the way he can use frame space to intensify the pressure on both his protagonists and his audience. Likewise, not long after, Roberts is moving through the lobby of an office building. She is shot from above, so that her movements around a large dividing wall seem like those of a mouse in a maze, all wasted effort and lost time.

In the earlier Pakulas, touches like these added up to something, became internalized into the story. Within the context of Grisham they seem like flourishes, afterthoughts attached out of frustration or boredom. If Pakula or Pollack were looking to the Grisham films as occasions to update their earlier works, they chose the wrong guy: Grisham's world is too essentialized. There is never any moral confusion and possibility of a downbeat outcome—what made the Seventies conspiracy thriller resonant. This hard jolt of reality is inconceivable for the Grisham hero.

Joel Schumacher is perhaps the quintessential Company Man, a maker of smooth, efficient entertainment, without a hint of soul, style, or vision. Perhaps he is not to be begrudged his success: Before jumping onto the A-list, he kicked around Hollywood for almost twenty years, first as a costume designer, then as screenwriter, and finally making the move to director—whereupon he proved adept at rendering most anything in the same flat, even style. Handed the Batman franchise, and clearly adrift and unable to continue in Tim Burton's dark brooding style, his only recourse was to camp it up and run the series straight into the ground. Perhaps Schumacher will ultimately be remembered as the man who achieved what so many supervillains could not: he killed the Batman.

A Time to Kill

If there is one thread that can be drawn from Schumacher's long, winding career, it is a rather strange relationship to the depiction of race. Early on he wrote the screenplays for Car Wash and The Wiz; the first was a surprisingly sensitive portrayal of underclass resentment, the other a shockingly ridiculous modern-day minstrel show, but both are filled with a certain spirit and joy. An early directorial effort, D.C. Cab, presents people of different backgrounds and ethnicities coming together, making the rather radical suggestion that the biggest dividing line in modern America is not race but class. Having made the jump to the A-list some time in the late Eighties, Schumacher first entered Grisham county with The Client (94), another sleek, by-the-rules “thriller” in which an inexperienced lawyer prevails against the big boys. All this made Schumacher the preeminent choice to shepherd to the screen A Time To Kill (96), Grisham's first novel and supposedly his personal favorite; it is the story of a racially heated trial in a small Southern town. But Schumacher submerges himself completely beneath Grisham's overly earnest tale, any trace of the quirkiness of his early work banished from the film in the name of efficiency—one of the reasons the film feels so dishonest. Its racial caricatures are all the more antiquated and ridiculous in light of Schumacher's earlier attempts at an honest portrayal of race in America.

At the other end of the creative spectrum from Schumacher, Coppola and Altman both find new ways to handle the Grisham cookie-cutter material instead of following preexisting rules. Coppola, once the demanding enfant terrible of Hollywood, has for the past decade or so astonishingly mellowed, working as a director-for-hire and in many ways bowing in subservience to the powers-that-be. Yet with John Grisham's The Rainmaker, he turns in the most personal of the Grisham films, exploring the same themes he had taken up in Tucker: A Man and His Dream. Coppola is able to connect with Grisham by finding the one thread that links to his own work and concerns: the fear of “selling out,” of giving up one's internal drive for purity, honesty, and dignity.

Coppola ends the film's opening titles with the image of a shark swimming across the screen—a looming figure soon revealed to be contained within a small tank. It is as if the director no longer feels trapped by Hollywood, is no longer antagonized by the concerns of the money-men, but has reached a point of equilibrium, where he understands what is needed for him to continue and stay on the safe side of the tank, out of harm's way. (Of course this notion is thrown off-balance by Coppola's recent spate of lawsuits against Warner Bros.; perhaps his biggest battles against the machine are yet to come.) The film concludes with a voiceover by the film's young lawyer hero (Matt Damon) that returns to these concerns, and there is no moment in the Grisham oeuvre that feels more personal, more honest. It comes as no surprise that the narration was written by Michael Herr, who also scripted the voiceover for Apocalypse Now. Feeling no particular reverence for the material itself, Coppola seems more comfortable than any of the other Grisham directors with twisting it to his own ends, making it say what he wants to say, not blindly mouthing another man's ideas as Schumacher does.

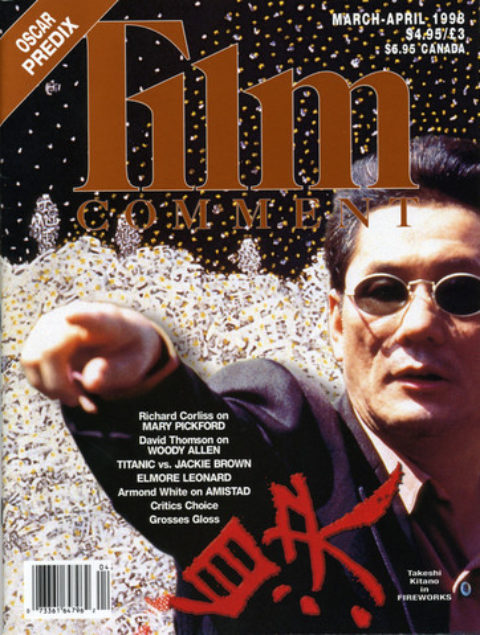

The Gingerbread Man

Which brings us to Altman. Though The Gingerbread Man is the first Grisham film based not on a novel but on a screenplay Grisham wrote, the novelist receives only story credit; screenplay credit goes to the pseudonymous “Al Hayes”: who knows who's responsible for what? Renowned for his ability to take convention and turn it on its ear, Altman's approach to Grisham is the most wary, and also the most difficult to take. The Gingerbread Man is no easy film to like, for it blocks most expectations about a “John Grisham Film” and thwarts the viewer at every plot twist. The other Grisham films establish their narrative drive as early as possible and spend the rest of their time plummeting headlong towards the good-over-evil conclusion. Altman's film is full of mini-plots, small asides, and ridiculously overblown chase scenes. One is never quite sure when the “actual” plot has begun, or where it is headed. Altman stakes his claim on the film largely by the confusion he creates.

Regardless of authorial origins, this film is in many ways Grisham-through-the-looking-glass. The main character (it is difficult to call him a hero), played with a rather disconcerting Southern accent by Kenneth Branagh, is one of the snaky, self-important lawyers we normally see on the other side of the table from Grisham's young, morally upright protagonists. Altman willfully avoids many of the house clichés, and those he does use he explodes by inflating them to the point of hyperbole. For example, the film is bookended by two trials we are not allowed to see, denying the heroic courtroom catharsis that normally defines Grisham's characters. The one legal hearing we are allowed to see is rendered a mockery by the Robert Duvall character's backwoods buffoonery. Where most Grisham films feature a single adrenaline-pumping chase to enliven things amidst all the courtroom chatter, Altman repeatedly picks up the pace, sending Branagh after multiple red herrings, so that when the final chase occurs its sense of awaited climax is diminished. By denying the courtroom theatrics, Altman avoids the conventionally moralistic center of Grisham's universe, where wrongs are righted and a higher justice prevails, encapsulated in the defining image of the Grisham film: the older, successful lawyer sitting surrounded and protected by clerks, yes-men, and researchers while the younger lawyer sits alone and vulnerable, armed with nothing but moral certainty.

If Altman seems at times to have nothing but contempt for his material, it is clearly directed at the moral superiority that permeates the Grisham universe. The Gingerbread Man is the only film in the cycle to present a world where no one is either all bad or all good. The only other film to even acknowledge this possibility is Coppola's—his young crusader chooses to walk away rather than face temptation and his own ethical battles. Altman dissolves entirely the absolutes of the other films, presenting a world of tough choices and tougher consequences, where instead of black and white, it's mostly shades of gray. In the struggle for authorship between Grisham and his adapters, the A-List pros surrender without a fight, with only Pakula showing any sign of resistance, while the craftier mavericks, Coppola and Altman, wrestle authorship away from Grisham through hostile take-over, keeping the auteur flame lit at the heart of corporate Hollywood.