Get Me Rewrite

The following is an excerpt from the July/August 2018 issue.

For a viewer, BlacKkKlansman keeps throwing things at you, just when you think you know what it’s going to be.

My films are not one thing. They have many different elements, mixed into subject matter, style, music… It’s a Spike Lee joint. It’s not just one thing.

A good example is how you open the movie with clips from Gone with the Wind and The Birth of a Nation. You shot a film referencing The Birth of a Nation way back when you were a student at NYU, right?

The Answer, which I did in my first year. That film is about a young, African-American writer-director who’s hired by a Hollywood studio to direct a big-budget remake of The Birth of a Nation.

From the very beginning, it seems like you wanted to redo film history, to correct it.

One of the reasons I wanted to do Miracle at St. Anna [2008] is that there is still a great absence of the admittance of the contribution of African-American women and men in the wars that they fought on behalf of the United States of America. So we’ve just been left out of history and left out of the films or TV shows dealing with historic events. The history of this country, or the world.

Was putting the footage from Charlottesville in BlacKkKlansman part of your intention to drive home that this is all really happening now?

From the beginning, when this deal was offered to me and then I brought in my co-writer Kevin Willmott, we wanted to find things in this period piece that would connect stuff so it was not just a history piece—that what you see in this film is really about the world we live in today.

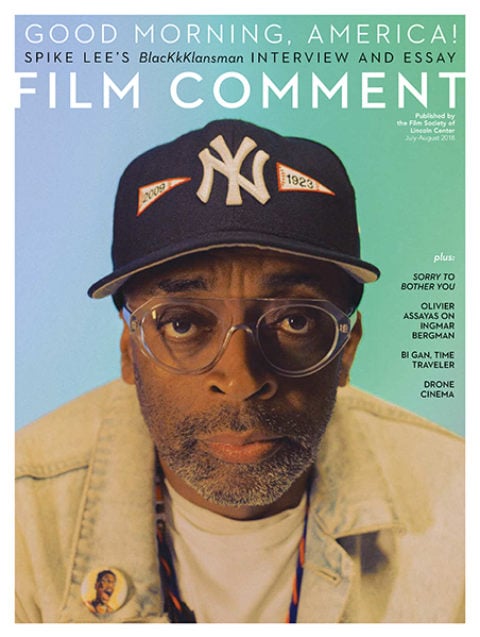

Spike Lee on the set of BlacKkKlansman. Photo: David Lee/Focus Features

Did you want a shock at the end?

I don’t know if I would use the word “shock,” because it’s not like people have not seen that footage before. August 11th and 12th is when Charlottesville happened, and we had not commenced principal photography. When I saw it, I knew right away that it would become the ending. So David Duke, Agent Orange, the Klan, neo-Nazis, the alt-rights—they gave me a tragic ending, and a life was lost there. It was homegrown, American terrorism.

Was the idea of an undercover detective interesting to you, how it connects to African Americans having to play two roles in society?

It’s interesting, but it’s not the first time I’ve done this in my films. And in fact we quote the very famous [text] by W.E.B. DuBois on the corrupted duality of being a negro in America, so we’ve always had this dilemma. It’s not new.

Generally it can feel like the country, the culture, is just catching up to you now.

I felt that for a while. Look, I’m not proud to say that. I wish people would have been hip to School Daze when it came out right away, or 25th Hour, or Bamboozled, and it seems that’s gonna happen with Chi-Raq.

Maybe you make movies that people need, but they don’t always know they need them.

[Laughs] I’ve never heard it put like that, but I’ll take it. I might use another word for need.

To read the rest of the article, you can purchase the July/August 2018 issue or subscribe now.

Nicolas Rapold is Film Comment’s editor-in-chief.