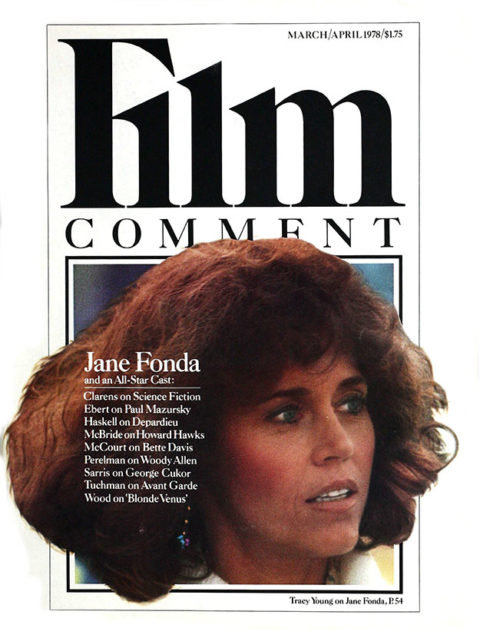

George Cukor

To celebrate the upcoming 50th Anniversary of the Film Society of Lincoln Center, Film Comment will be making some classic pieces from our archive available online. First up, read Andrew Sarris’s salute to the legendary filmmaker and FSLC’s 1978 Chaplin Award Gala honoree.

I met George Cukor only once in my life, and then only very briefly, but I have enjoyed the movies he directed through most of my other life up there on the screen, and I thought that I had written both appreciatively and perceptively of his career as a whole in The American Cinema. Nonetheless, I felt a distinct chill in his very perfunctory greeting, and I must say that I was not entirely surprised. Despite my great affection and admiration for much of the maligned output of Hollywood, I have never gone out of my way to meet its artists and craftsmen. For one thing, I have always lacked both the talent and the temperament to function as a tape-recorder critic. For another, I consider it a form of cheating to check my critical insights with the horse’s mouth. The evidence on the screen should be sufficient.

Little Women (1933)

Besides, until very recently most Hollywood directors had been relatively unpublicized cogs in the production machinery of the great studios. Aside from some quaintly quirky “characters” like Lubitsch, Hitchcock, and De Mille, the Hollywood director tended to be an esoteric detail in workaday movie reviewing. Orson Welles tried to change all that with Citizen Kane, but he was quickly driven out of Hollywood for his egotistical exhibitionism. Welles was perhaps the first self-proclaimed auteur since Griffith, Chaplin, Stroheim, and Sternberg, and look what happened to all of them!

One need only listen to the endless litany of gushy collectivism on the annual Academy Awards ceremony to understand how tenaciously Hollywood clings to the ideal of the team player even in a community in which every individual doubles as his own personal press agent. Also, Hollywood has never been much of a haven for film history. As far as the industry is concerned, you’re only as good as your last picture, and well-meaning film historians only make matters worse by pontificating about your past glories. In Cukor’s case, he had always done better with the moguls than with the mandarins anyway. Although the Selznicks, the Mayers, the Thalbergs, the Warners, the Zanucks, the Zukors had not provided a picnic ground for Cukor throughout his career—toward the end, particularly, they mutilated many of his most promising productions—they had accorded him also the very considerable respect due one professional from another. Without this respect he could not possibly have made the close to 50 films in a career spanning nearly half a century.

Unfortunately, critics and historians have been singularly condescending to Cukor. Lewis Jacobs, in The Rise of the American Film, gives short shrift to Cukor’s work in the ’30s: “Although George Cukor has been directing pictures only since sound and Sidney Franklin practically grew up with movies, the qualities of these directors are fairly similar. Their productions are carefully planned and lavish, but marked by theatricalism. Like Brown and Borzage they get only the highest-priced story or play material, the biggest stars, the most expert technicians; no expense is spared to make their enterprises outstanding. It is, however, only by their fine taste and attention to acting that their films are distinctive. Their renditions are for the most part static, suggesting the stage plays and stage tradition from which their style stems… Although both directors are meticulous workers, their elaborate approach is narrow and confined, with only occasional feeling for the movie medium as such.”

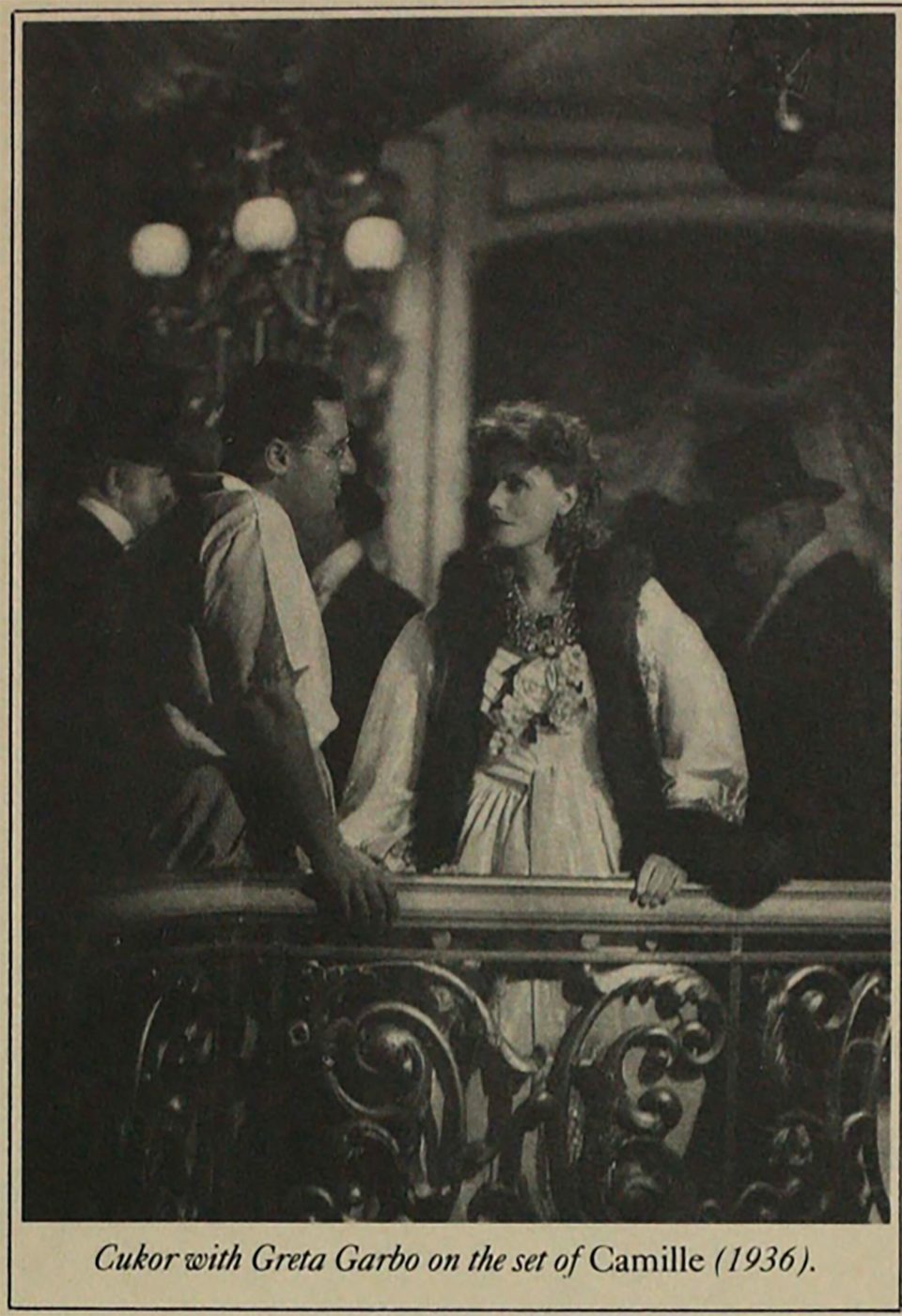

The late Richard Griffith in The Film Till Now gave even shorter shrift to Cukor: “Among directors whose experience is confined to the sound film, George Cukor and William Dieterle were the first to assume importance. Cukor occasionally attempts to explore the medium as such-more or less after the manner of Hitchcock—as in What Price Hollywood? (1932) and Gaslight (1944), but for the most part is content with conventional adaptations of stage successes, old and new (Our Betters, 1933; Camille, 1937; The Philadelphia Story, 1940). He is, in a manner of speaking, a William De Mille or Maurice Tourneur of the talkies, tasteful, meticulous, but without interest in, or flair for, the film itself.”

Further on in The Film Till Now Griffith made a cryptic reference to Cukor’s camera style in the midst of a favorable analysis of Charles Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux: “The moving or panning camera, that salvation of George Cukor, is rarely employed, and then almost entirely in mute scenes.” It would seem, at least according to Griffith, that “a flair for the film itself” was antithetical to “the moving or panning camera.”

Even a comparatively sophisticated film critic like the late Otis Ferguson had to overcome his preconceptions about Cukor before he (Ferguson) could write a wholehearted rave about Greta Garbo in Camille: “But although George Cukor’s direction has seemed to be on the consciously classic side previously, his work here with the cast, material (treatment credited to Zoe Akins, Frances Marion, James Hilton), and technical staff (the top MGM crew: Herbert Stothart, William Daniels and Karl Freund, Cedric Gibbons, etc.) is a firm and straight-out piece of film work.”

Camille (1936)

A few years ago, David Susskind presided over a panel of Hollywood people, three of whom were the directors Richard Brooks, George Cukor, and Fred Zinnemann. It became clear during the course of the program that Susskind respected Brooks, revered Zinnemann, and dismissed Cukor as a “woman’s director.” Susskind, long considered a male chauvinist swine among male chauvinist pigs, may have simply used Cukor as a whipping boy for all the big-star women’s pictures that were deplored by realist and Marxist film aestheticians over the years. Cukor, after all, had directed both Little Women and The Women (1939), not to mention more Katharine Hepburn vehicles than anyone could remember off-hand. Certainly, an anti-Hollywood snob like Susskind would hardly feel more kindly disposed toward the so-called “man’s directors” like John Ford, Howard Hawks, or Raoul Walsh. To Susskind, a director like Zinnemann represented neither women nor men but rather the bloodless, sexless abstraction once designated by Stan VanDerBeek as “Mankinda,” a “humanistic” balloon blown up with the hot air of social consciousness.

It was against this background of Cukor mockery that I launched my defense and revaluation of Cukor in The American Cinema: “George Cukor’s filmography is his most eloquent defense. When a director has provided tasteful entertainment of a high order consistently over a period of more than thirty years, it is clear that said director is more than a mere entertainer… Even Cukor’s enemies concede his taste and style, but it has become fashionable to dismiss him as a woman’s director because of his skill in directing actresses, a skill he shares with Griffith, Chaplin, Renoir, Ophuls, Sternberg, Welles, Dreyer, Bergman, Rossellini, Mizoguchi, ad infinitum, ad gloriam. Another argument against Cukor is that he relies heavily on adaptations from the stage and that his cinema consequently lacks the purity of the Odessa Steps. The argument was refuted in principle by the late Andre Bazin. There is an honorable place in the cinema for both adaptations and the non-writer director, and Cukor, like Lubitsch, is one of the best examples of the non-writer auteur, a creature literary film critics seem unable to comprehend.”

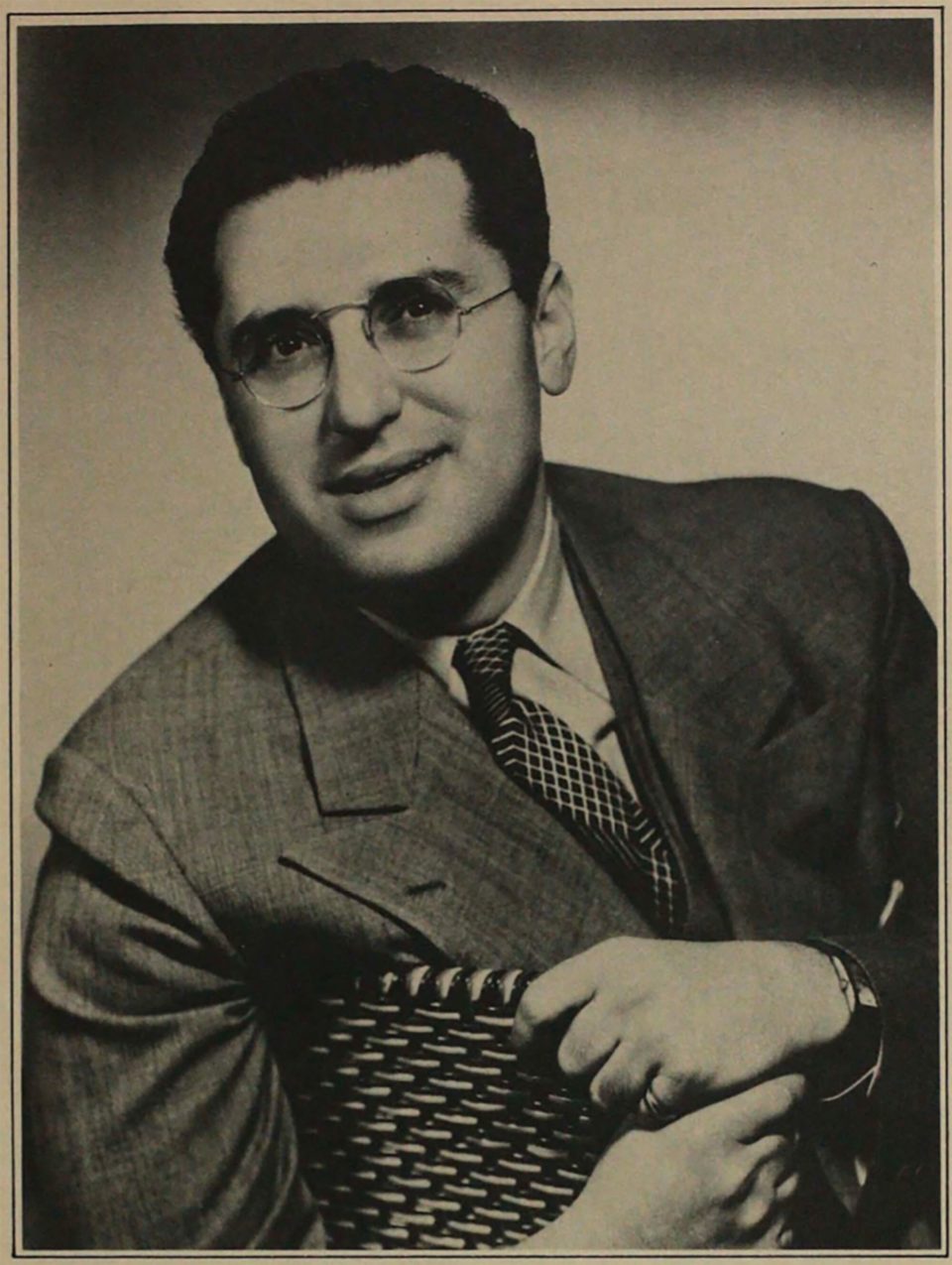

I did not realize at the time I was writing The American Cinema, now more than a decade ago, that Cukor’s critical reputation was a more complicated subject than I had imagined. Nor had I correctly added up all the pluses and minuses in his career. As it happens, I have now finally seen all his films except Grumpy, and I am thus in a better position to evaluate his ultimate position in the history of movies, a position that must take into account the fact that he began in pictures as a director of dialogue, and that his good ear for dialogue as it is spoken could alone make him a titan of talking pictures. Through the ’20s Cukor had acquired theatrical expertise in Rochester and on Broadway with such properties as The Great Gatsby, The Constant Wife, Her Cardboard Lover, The Dark, The Furies, A Free Soul, Young Love, and Broadway. Cukor himself remade Her Cardboard Lover as a Metro swan song for Norma Shearer in 1942. He came to Hollywood as a “dialogue director,” and he continued to function in that capacity for the rest of his career.

Curiously, the celebrated turnover of actors and actresses with the coming of sound did not extend to directors. Of the directors imported to Hollywood expressly to handle the dialogue only Cukor, Mamoulian, and Cromwell survived into the ’40s from the Broadway crop, and only Dieterle and (later) Preminger from abroad. Ford, Sternberg, Hitchcock, Hawks, Lubitsch, Lang, Capra, McCarey, Milestone, Borzage, LaCava, Vidor, Walsh, Wellman, Stevens, Stahl, Curtiz, Le Roy, Howard, King, et al. had all paid their dues to the muse of the silent cinema. It was therefore very easy to tag Cukor as a baleful “theatrical” influence on the once virginally visual cinema.

Still, there were plays and there were plays. Cukor never seemed to get the rough, lusty, muscular, and, above all, messagey assignments like Anna Christie, Street Scene, The Petrified Forest, Dead End, The Children’s Hour, and Idiot’s Delight. The Harlow-Beery roughhouse in Dinner at Eight was about as raucous as a Cukor project ever became. Cukor did not choose to prowl around the dark alleys of the gangster movie with its dese-dem-dose dialogue, nor to roam the wide open spaces of the Western with its long silences. He was interested instead in civilized men and women with a certain amount of spunk in them, and one would think that this particular orientation would have struck a responsive chord among the members of the proverbial Algonquin Circle. Unfortunately, the New York intelligentsia made it a point of honor to despise all movies indiscriminately, and Cukor was never given a chance to make points with his proper constituency.

The Philadelphia Story (1940)

Also, his career hit several snags. At Paramount he became embroiled in a feud with Lubitsch over One Hour With You. Two of the finest films of the ’30s by any current standard—Dinner at Eight and Holiday—were inexplicably underrated. Far from looking like canned theater today, these two masterpieces of modulation vibrate with a distinctively cinematic sensibility. Similarly, Little Women and David Copperfield have been dismissed as canned novels despite their fierce beauties of expression. Rowdy fun movies like Girls About Town and What Price Hollywood? got lost in the shuffle, and out-and-out box-office bombs like Sylvia Scarlett and Zaza never acquired the cult following they eminently deserved.

The story was that Cukor thrown off Gone with the Wind because of Clark Gable’s suspicion that his performance was being neglected for sake of Vivien Leigh’s and Olivia de Havilland’s probably consolidated the canard of the woman’s director, particularly when Cukor was reassigned to The Women, a project in which no male appears on the screen. But Cukor never got credit for directing Leigh’s two best scenes: Melanie’s childbirth sequence in silhouette, and the shooting of the Yankee deserter at Tara. Under Victor Fleming’s lackluster direction, Leigh’s performance is spectacularly uneven, and her final parting from Rhett is bungled.

It is not simply a question of Cukor’s being a better director of actresses than Fleming. Performances do not flower in a vacuum. One must direct the time and space around the performers through choices of pace and focal length. Hence, a full-fledged movie director had to emerge out of the exquisite performances of Ina Claire in The Royal Family of Broadway; Tallulah Bankhead in Tarnished Lady; Kay Francis and Lilyan Tashman in Girls About Town; Lowell Sherman in What Price Hollywood?; Katharine Hepburn and John Barrymore in A Bill of Divorcement; John Barrymore, Marie Dressler, Jean Harlow, Wallace Beery, and Karen Morley in Dinner at Eight; Hepburn, Jean Parker, Paul Lukas, and Edna May Oliver in Little Women; Roland Young, W.C. Fields, Edna May Oliver, Basil Rathbone, Maureen O’Sullivan, and Madge Evans in David Copperfield; Hepburn, Cary Grant, Edmund Gwenn, and Natalie Paley in Sylvia Scarlett; Greta Garbo and Rex O’Malley in Camille; and just about all the women in The Women.

But the early ’40s found Cukor locked into a series of Metro vehicles, most of which broke down long before the final fade-out. Crawford, Hepburn, Garbo, Shearer gave their all, but only Hepburn emerged unscathed: The Philadelphia Story recharged her career in the company of Cary Grant and James Stewart, and Keeper of the Flame, an otherwise flawed political melodrama, revealed her at her most stunningly beautiful opposite Spencer Tracy. Crawford continued her long slide at Metro with Susan and God (despite Fredric March’s vulnerably pensive accompaniment) and A Woman’s Face (despite Conrad Veidt’s demonic brilliance). Garbo retired after Two-Faced Woman and Shearer after Her Cardboard Lover, at which point Cukor himself was marked as an unresisting company man for MGM.

Otis Ferguson’s commentary on the Cukor Two-Faced Woman could have served as the director’s epitaph as a creative force in Hollywood: “Now Miss Garbo is seen in another company, but with the direction of George Cukor, who is apparently a director careful to the point of elegance but always at the mercy of what the boys have cooked up for script. Since he is in the pleasant, easy latitudes of the top-budget ‘A’ group, he can take his time in following the tortuosities of a script that waste the audience’s. If a writer lugs his uncle’s wife into the story for no other purpose than that of padding out the chore of his contract, Mr. Cukor will apparently be patient and even elegant on the job of importing the writer’s uncle’s wife. The writers of Two-Faced Woman were Samuel Behrman, Salka Viertel, and George Oppenheimer, and occasionally they seemed tired. At such points the director yawned himself, out of carefulness, elegance, and politeness.”

By the time of Pearl Harbor, Cukor was thus being written off as a docile contract director. No one knew at the time that he had two dozen more films in his system, and that he would manage to ride out the industrial convulsions that would eventually convert even mighty Metro into a mausoleum. Up to 1944 only James Stewart had won an Oscar in a Cukor movie, and Stewart’s award for The Philadelphia Story was widely regarded as delayed compensation for his not getting an award for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. But in the next 20 years, Ingrid Bergman won for Gaslight, Ronald Colman for A Double Life, Judy Holliday for Born Yesterday, Rex Harrison and finally Cukor himself for My Fair Lady.

Adam's Rib (1949)

Cukor’s collaboration with Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin led to seven of his brightest and most venturesome works: A Double Life, Adam’s Rib, Born Yesterday, The Marrying Kind, Pat and Mike, The Actress, and It Should Happen to You. Curiously, both Born Yesterday and My Fair Lady were relatively stodgy, overblown works like Romeo and Juliet (1936) and Edward, My Son (1949). By contrast, more conventionally plotted movies like A Life of Her Own and The Model and The Marriage Broker revealed a new virtuosity in establishing mood and ensemble interplay despite the glamorously superficial lead performances of Lana Turner and Jeanne Crain, respectively.

Cukor’s association with special color adviser George Hoyningen-Huene began with A Star Is Born in 1954. This achievement in dazzling widescreen modernist compositions prompted a critic for Cahiers du Cinéma to declare: “A DIRECTOR IS BORN!” With his first color film (and Judy Garland, James Mason, and Harold Arlen besides), Cukor left behind the old black-and-white studio tradition of the ’30s and ’40s, and became a critically chic director for the ’50s and ’60s and (in some quarters at least) the ’70s with such chromatically delirious canvases as Bhowani Junction, Les Girls, Heller in Pink Tights, The Chapman Report, Travels with My Aunt, and suddenly Cukor unveiled a very imaginative form of sensuality in the suggestive performances of Ava Gardner (Bhowani), Sophia Loren (Heller), Jane Fonda and Claire Bloom (Chapman), and even Maggie Smith in Travels. Advanced film scholars solemnly debated the stylistic contrasts between Cukor and Minnelli. Doctoral theses were submitted on the treatment of transvestism in Cukor (Sylvia Scarlett, Adam’s Rib) and Hawks (Bringing Up Baby, I Married a Male War Bride). But after My Fair Lady the old box-office magic was completely gone, and the bleached bones of The Blue Bird were chewed up by the bottom-line vultures.

It is no wonder that Cukor was cool to me. I probably represented all the well-meaning amateurs of Academe who had come to embalm him with admiration while he was still trying to line up one more big project. For my own part, I may have once overrated Cukor—and I apologize for this act of critical overcompensation—but it is well and good that most of the voices that ridiculously underrated him are now forever silent. The Film Society of Lincoln Center has made an unusually perceptive move in choosing to honor George Cukor, Dialogue Director Extraordinary, and yet discoverer also of the magical spaces around the actors on the screen.

Born Yesterday (1950)

Excerpts from the Film Comment interview with George Cukor by Gene Phillips (from the Spring 1972 issue):

How does directing films differ from directing for the stage?

In films you are working in very close quarters; in the theater the actors have to act with their voices in order to project to the back of the house. The director has to keep in mind when making a film that what is a good performance for the stage would be overacting on the screen. I came to Hollywood about the time that sound came in and the studios were all petrified. Directors were abandoning all that they had learned about camera movement in the days when they were making silent films. The camera was in a soundproof booth so that mechanical noises would not be picked up on the sound track. The director had to use a different camera for long shots, medium shots, and close-ups for this reason. Gradually the techniques of making sound films were perfected, however. I was dialogue director on the first picture on which I worked. Then I moved up to directing, but it took me three or four years to cotton on to screen directing after coming from the theater.

As a contract director in a big studio in the ’30s were you allowed much freedom?

The contract directors were allowed some freedom. A lot of people who talk today about studio interference in the old days weren’t around then. It’s true that an unintelligent producer might sometimes stick his nose into the director’s work, but a lot of interesting personalities were developed and a lot of interesting films were made, so someone must have been doing something right in the big-studio system. Although I must say that I was not the kind of person Louie B. Mayer liked, he and Irving Thalberg collected a great roster of players at MGM and made the American picture industry known throughout the world. They had vitality and conviction, qualities that have since been lost in the industry to a great extent.

You have been said to be very effective in working with actors, especially female stars such as Katharine Hepburn, Ingrid Bergman, Judy Garland.

As I have said on other occasions, I achieve practically all my film effects through actors and actresses. Perhaps it is because of my stage background. Other directors get their effects by photographing a turning doorknob, etc. I like to concentrate on actors’ faces. I suppose there is some stamp on my work, but I cannot see it myself. For example, I don’t think that I want to show the American woman in any particular light.

One of your wide screen films happens to be one of the most successful films of all time: My Fair Lady, which is right now receiving a general re-release.

Even though I received an Academy Award for the picture, I have never really felt at home in making musicals. I don’t know enough about music to put songs in the proper places within the action of the story. Of course in the case of My Fair Lady we had the original stage version to go by. But the transition from stage to screen is tricky. On the one hand you can’t turn out a photographed stage play; on the other hand you can’t rend the original stage version apart. If you don’t know what the hell was good about the original play, you pull it apart to make a different version for the screen and you have nothing left. Shaw had worked on the script for the screen version of his Pygmalion [1938] on which My Fair Lady, of course, was based. In it he allowed the ending of his play, in which Eliza and Henry Higgins did not get back together, to be changed so that the story ended happily. Lerner and Loewe used this ending for My Fair Lady on the stage and we kept it in the film.

Visit our store for more great interviews, reviews, and features from over 55 years of Film Comment.