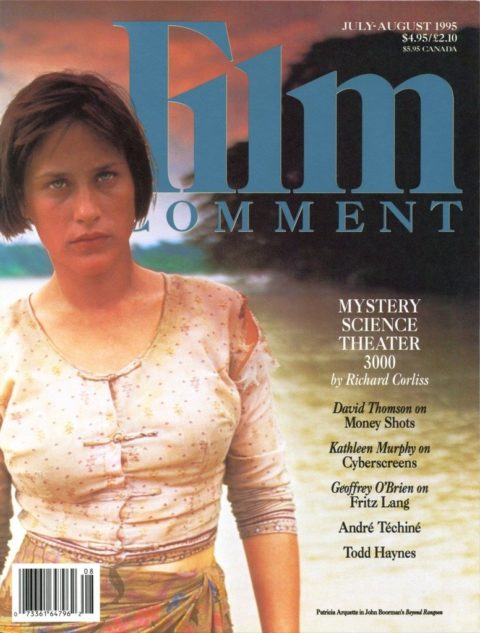

Gentlemen Prefer Haynes

John Travolta’s immuno-deficient Boy in the Plastic Bubble and Joseph Cornell’s jeweled-beetle dioramas; Jean Genet’s radiant convicts and Alfred Hitchcock’s tormented dolls; homemaker Jeanne Dielman and chanteuse Karen Carpenter; Sigmund Freud’s elaborative slapstick and I Love Lucy’s interpretation of dreams. Run a namecheck on Todd Haynes’s influence-roster and you’re likely to find yourself wading through a palimpsest of moldering TV Guides and fine art melodramas, random gross-out images from fringe horror flicks, and a few impenetrable back numbers of the critjournal Screen. Is there another contemporary independent filmmaker whose remote-control rifling through American teleculture and European high conceptualism emerges in films politically engaged and free of Peckinpah-inspired male-crisis blood squibs? Is there another young American filmmaker whose work so thrives on contradiction?

Haynes’s career-founding 45-minute featurette, the Barbie-mation imitation of life, Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, presaged the still-cresting wave of Seventies revivalism, yet due to the intervention of Richard Carpenter and A&M Records remains out of circulation after the better part of a decade. His ambitious first feature, three interwoven, body fluid-drenched tales of “transgression and punishment” entitled Poison, amply nourished his fame even as its partial EA funding prompted culture-sheriff The Rev. Donald Wildmon to issue a headline-grabbing condemnation. Even the relatively naturalistic Dottie Gets Spanked utilized the most conventional of forms—early-Sixties sitcoms—to unearth the sadomasochistic cant of a prepubescent boy’s elaborate fantasy life. Haynes’s latest (and first 35mm) feature, an emotionally devastating examination of “environmental illness” entitled Safe, suggests those contradictions may have only just begun.

Hand Held: Superstar

Haynes: “My sister Wendy didn’t really have Barbies as a child, but we would spend a lot of time playing with her collection of plastic horses. We’d put a blanket over her bedroom table and use the desklamp as a light source, and I’d go nuts creating these ornate stories about a little girl who got a horse for her birthday, which then got injured and had to be shot—and she’d cry as I’d act out these really sad melodramas. And I think Superstar really owes a lot to those years under the table with my sister.”

Or you might blame it on Brown, from where Haynes graduated in 1985, gripping a B.A. (with honors) in Art and Semiotics. Steeped in Critical Studies, and fixated on his close reading of Freud’s “A Child Is Being Beaten” (which examines the transformation of masochism into sadism in the spanking fantasies of the young), Haynes found the subject for his now-infamous 1987 cult treasure, Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (co-written and produced by Cynthia Schneider), on the Lite FM airwaves, when a chance encounter with The Carpenters’ “Yesterday Once More” sent him into a reverie of preteen life in his native Southern California. “The early Seventies had felt like the last moment of pure, popular culture fantasy and fakeness that I shared with my parents, when we were still united in this image of happy American familyhood,” Haynes would later explain. “And The Carpenters’ music seemed especially emblematic of that time.”

Further flashbacks ensued. Recalling a promotional film he’d seen on The Mickey Mouse Club as a child, in which Barbie and her plastic-perfection wish-fulfillments were introduced to a nation of pint-sized consumers, Haynes began to link archaic images to his current fascinations: the politics of the body and the coercions of fame, parental control and poststructuralist chaos, cinema’s yin-yang of identification and estrangement. Captivated by the cultural implications of Karen Carpenter—“the smooth-voiced girl from Downey, California, who lead a raucous nation smoothly into the Seventies” (per Superstar’s “authoritative” voiceover) before succumbing to anorexia at age 32—Haynes resolved to cast his film with carefully modified dolls: Malibu Barbie, meet Bertolt Brecht.

Superstar’s blend of genre appropriation and dollhouse kitsch is at once giddy and awful. It opens, under the cautionary title “A Dramatization,” with a well-worn schlock-horror trope—a murky, handheld search through Karen’s spacious condo, shot from the perspective of an unseen Mother Carpenter (who calls in vain for her unresponsive “Carrie”). The initial archness of Haynes’s foppishly bewigged and elaborately turtlenecked dolls quickly recedes, and the film wastes no time searching out hars her truths: Karen’s skyrocketing career is countermanded by her controlling parents, and her reaction-starvation dieting and an addiction to Ex-Lax—soon reaches epic proportions. Haynes’s control of his doll-world escalates as well, and soon his plastic performers’ complexions become scoured and stained, their “flesh” stripped away and “aged.” The director’s Freudian spanking obsession also reveals itself in the assorted rhythmic punctuations of a human hand smacking a tambourine and tweaking a radio dial, and most tellingly in a grainy image from Karen’s dreamlife, as a huge human hand helps Poppa Carpenter paddle little Karen’s exposed derriere.

But while Haynes’s melo-dioramas and micro-mise-en-scene—an impressive array of tracking shots, swish-pans, and up-up-and-away “cranes” through exquisitely Contact-papered minisets suggest a foray into Lilliputian Sirkiana (or its drained, Eighties equivalent, the Movie of the Week), his darkly associative montage takes off from the found-footage lessons of Bruce Conner. In one sequence, under the saccharine strains of “We’ve Only Just Begun,” Haynes asserts the collapse of history as bitter flashback, comprised of Cambodian bombings and concentration camp body-dumping, Richard Nixon tinkling the ivories, and assorted catastrophic fragments from The Poseidon Adventure. Elsewhere, the plight of the anorexic (whose “distorted perceptions of their actual body size” Haynes’s approach cleverly mimics) is discussed in solemn voiceover, while slow camera cruises through suburban neighborhoods underscore postwar America’s cultural climate of super(market) abundance.

In October 1989, after scores of successful bookings and enthusiastic reviews, A&M Records enjoined Haynes against further distribution of the film. Despite his offer “to only show the film in clinics and schools, with all the money going to the Karen Carpenter memorial fund for anorexia research,” Superstar remains buried. (A brisk bootleg-video life is rumored.)

Poison - 1991

The Antidote: Poison

Haynes: “What was most fascinating to me about ‘A Child Is Being Beaten’ is the masochistic subtext Freud reveals behind his patient’s fantasies/memories of witnessing beating scenes: a subtext that reveals the person as the child being beaten, as opposed to being an observer and watching it gleefully from the sidelines. That’s so interesting to me, how sadism becomes a more acceptable version of masochism culturally.”

A slow-acting compound of apparently incompatible substances, Haynes’s feature-length Poison (’90) intercuts a triptych of stylistically divergent episodes, each set in a world “dying of panicky fright.” “Hero,” shot in the talking-head manner of televised newsmagazine, uses interviews with neighbors and schoolmates to construct a portrait of a preteen boy, who, according to his mother, murdered his abusive father and flew off into the sky. “Horror” takes its campy expressionism and comic-paranoid cues from the Waters-Kuchar school of aggressively mutated Fifties B flicks: a repressed medical researcher isolates a liquid version of the human sex drive and is transformed into a pathetic, pus-oozing ghoul. “Homo,” a lusty, bruised pastiche of Jean Genet’s prison writings, inflected by Fassbinder’s rough-trade penile codes and shot in alternating tones of rosy passion and steel-blue brutality, concerns a career thiers consummation of his longing for a fellow inmate.

Each story is fraught with the consequences of being named. “Hero”’s sub-urban urban Richie Beacon so identifies with his mother’s conjugal loathing (finding her in bed with the family gardener, Richie flashes on a memory of being paddled by his father) that he needles his disgusted schoolmates into complying with his spanking fantasies. But was he a “meek soul,” or a “liar” who once shat in his neighbor’s yard? A “manipulative” hellion or, as his mother (played with maximal denial by Edith Meeks) prefers it, “a gift from God”? In “Horror” Dr. Graves, for whom “science, man’s sacred quest for truth” was his only love, becomes momentarily distracted by the pert twitches of his new assistant and mistakes his sex-drive distillation for his coffee cup. Unforgivably, he begins to externalize his desires in the form of oozing pustules (which, in one of the film’s many money-shots , drip onto a hot dog in mid-bite). Dubbed the “Leper Sex Murderer,” Graves horrifies the city’s roving mobs of repressed hetero-normals as he infects them with similar urges.

In the film’s most impassioned tale, Broom (hungry-eyed Scott Renderer), a convict at Fontanel Prison, becomes obsessed with Bolton (a sultry James Lyons), beset with arousing recollections of him as a small, victimized adolescent in the borstal where they once did time as youths. Juxtaposing florid memories of the borstal’s crumbling idyll—where, in the film’s tour-de-force of ecstatic humiliation, Bolton’s tormentors seem to bob in the heavens, showering endless gobs of phlegm into his mouth and face—with the wet-stone blues and brutish denials of Fontanel, Haynes rhymes Broom’s transformation from Bolton’s masochistic sympathizer to furtive lover and sadistic ravisher, with Richie Beacon’s patricidal acting-out. Richie’s final, skyward flight is a bleak complement to Broom’s continuing incarceration: both have acted honestly on their confusions of longing and sexual violence, and both, in effect, murder the objects of their desires. Dr. Graves, by comparison, becomes a suppurating martyr to his “dark” urges, and in his death succeeds only in reverting to repression, confusing the buzzing of a fly (the episode’s film generic touchstone) with the beating wings of a grubby angel.

In its ever-tightening, Intolerance-like weave, Poison’s echo chamber of earthly limitations and celestial boundlessness, deadly secretions and beautiful spew, succeeds in engaging topicality precisely by repressing it. The film’s silent meditation on the climate of crisis and sexual fear that produced it may be its most enduring quality: by refusing to address AIDS by name, Poison concocts a subversive, if purely formal, antidote of destruction and transcendence.

Dottie Gets Spanked - 1993

Rear Projection: Dottie Gets Spanked

Haynes: “My parents didn’t believe in spanking, but I do remember that once when I was about three my dad lost control and did spank me. I don’t remember it being a highly charged erotic experience; in fact, I remember feeling very indignant, and very righteous in knowing that this was not what we believed in our family, and yet I was still being subjected to it.”

Haynes’s first foray into television production, the elegantly anguished hourlong Dottie Gets Spanked (’93)which he describes as having the “quality of an Afterschool Special, or a sweet little valentine”—was created for the Independent Television Production Service’s “TV Families” series and broadcast on PBS.

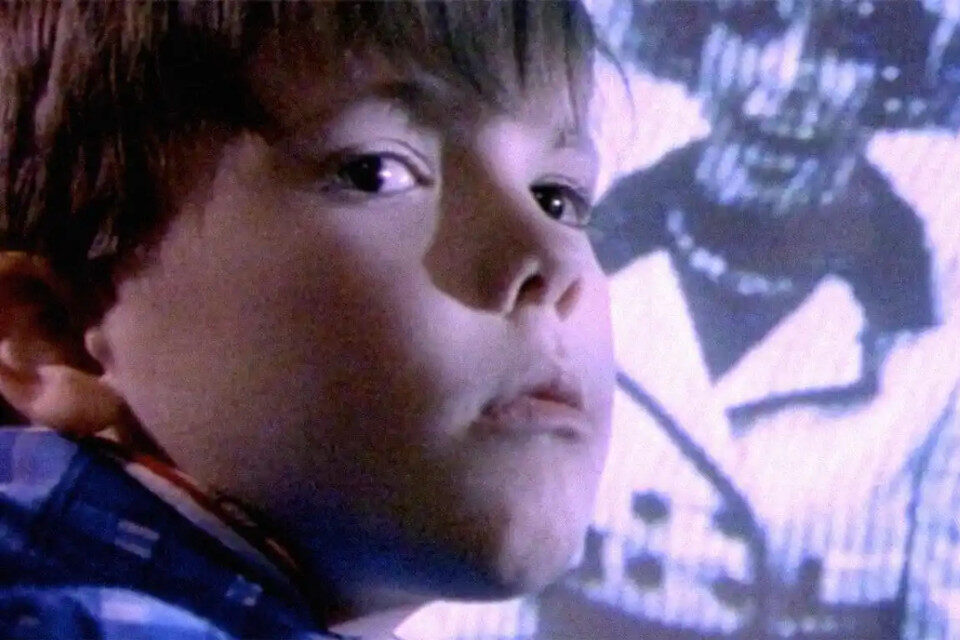

Turning on the director’s own childhood fascination with certain female TV icons, Dottie follows a short but developmentally conclusive period in the life of young Steven Gale, a withdrawn, cherry-cheeked lad of seven who spends much of his time fantasizing about The Dottie Frank Show. Heckled by his male classmates and tormented by the little girls down the street who screechingly label him a “feminino” for sharing their Dottie fixation, Steven (played to abject perfection by Evan Bonifant) loses himself in fanciful drawings based on his nose-to-the-tube televisual research: condensed, crayon scenarios in which Dottie encounters such luminaries as Julie Andrews, and a single self-portrait he entitles “Cinderfella.”

Steven’s dreamlife is equally rich: he oneirically constructs a black-and-white, de Chirico kingdom (complete with kiddie reconfiguration of Poison’s prison, just as Steven is Richie Beacon’s potential predecessor) over which he rules from atop a towering throne. Foremost among the contents of Steven’s nightsuites are fantasies of power, many involving elaborations on corporeal themes. Primarily he envisions the fate of one female tormentor as she struggles in the throes of a severe paddling—a fate Steven both covets and abhors.

Throughout Dottie, these desires and terrors mingle and collide, and Steven’s psychic confusions become ever more fraught. Ultimately Steven wins a trip to the set of Dottie’s show, and the manufactured reality he encounters in the studio palace of his Queen of Comedy—the filming of an episode in which Dottie is herself spanked by her angry husband—unleashes a torrent of visual and emotional complications. Haynes bombards Steven (and the viewer) with cross-dressing body doubles (Dottie, in and out of costume, as well as her buxom stand-in), murky secondary revisions (color, black-and-white, video, and crayon variations on images of Dottie over her paddler’s knee), and “frank” multiple entendres.

Further upping the film’s psycho-biographical ante, Haynes shoots Steven’s waking hours in the oversaturated Eastman-tones of old home movies and finds myriad opportunities to embellish and subvert its ostensible naturalism with commercials for Fab-u-lash (emphasis mine) mascara, or with snippets of Dottie sing-songing the nursery rhyme refrain “wagging their little tails behind them.”

The flood finally becomes a whirlpool, and Steven’s dreamlife, now gorged with spankings and mustachioed Dotties, spirals ever outward towards the film’s inconclusive final image: Steven’s hand patting the earth after burying his drawing of Dottie receiving her spanking—the image that compels Steven’s father to terminate his viewing privileges. “It’s a gesture that reiterates the act that’s been banned, and that’s been repressed in the act of repressing the act,” Haynes admits of Dottie’s culminating shot, with typically Freudian elusiveness. “It implies a whole future movie, where the repressed is of course unburied.”

Such are the lessons of Dottie Gets Spanked: a “sweet little valentine” that smacks more of autobiographical open heart surgery; an “afterschool special” that reconsiders the fascinations of childhood from a deeply media-suspicious adult vantage; a portrait of the artist as a young man who’s finally learned the dangers of sitting too close to the screen.

Safe - 1995

Safe’s Sects

The mausoleum-chilled irony and measured, synthrock rhythms of Safe are so patient and exquisite, so tempered and austere, that they almost obscure the film’s desperately beating heart. Almost.

San Fernando Valley “homemaker” Carol White (Julianne Moore) finds her immune system slowly being compromised by “environmental illness”: the catastrophic, all-encompassing allergy to the 60,000 chemicals in daily use that has baffled the medical establishment and gained the moniker “20th Century Disease.” But what’s to blame? The apparently anesthetic suburban spaces through which she moves: grand “living” rooms and cavernous carparks, clotted freeways and spotless spas? The mysterious fumes from a passing truck, the gurgling Bride of Frankenstein perm she receives, or the fruit diet her girlfriend recommended? The numbing paces of her husband’s “lovemaking,” all pump and grunt, through which she dutifully cradles him, a patient nursemaid to his joyless convulsions? Or is Carol herself the problem: a pleasant if humorless Stepford wife, driven by carpool rituals and honed by aerobic drill instruction, looking like an emaciated replicant, a luminous pod, never breaking a sweat?

Set-dressed in immaculately artificial teals and blushes, and shot by Alex Nepomniaschy in vast, ultrawide angles that reduce all human activity to miniaturized doll-movements, Safe is as steeped in quotidian paranoia and nouveau-riche malaise as anything in the Antonioni canon: there’s scarcely a human closeup in the film (Haynes screened 2001 and Jeanne Dielman for his crew). As Safe’s “silences” whine with vacuum-cleaner roar and television drone, every radio station issuing an AOR water torture or the nattering of some call-in calamity, Carol’s identity gradually undergoes complete shutdown. “Who am I?” she wonders with quiet, pink-eyed desperation at the film’s heartbreaking midpoint.

That Carol’s first “line” is a sneeze underscores the way that Safe is everywhere already in tune with the “deep ecology” of an assortment of millennial ills. Much like its heroine’s illness, it demands to be read by its symptoms. What is unexpected about Safe is that it both plays on the apparent “comfort and resolve” (Haynes’s words) of the average movie-of-the-week, and quietly subverts the rhetoric of its recovery guru Peter Dunning (sleek, beady-eyed Peter Friedman), a “chemically sensitive person with AIDS” to whom Carol turns for help. It is at the callow Dunning’s Southwestern retreat, Wrenwood, spends its second hour.

A scene that illustrates the subtle dialectics at play: Carol, looking more gaunt and wasted than ever—“adjusting” to life at Wrenwood—is approached by Peter, concerned over her reluctance to join in group-think. Carol, with all the conviction she can muster and eager to fit in, admits to Peter that she’s “still just, you know, learning the words.” “Well,” Peter sighs, “words are just the way we get to what’s true.” Then, as Peter gazes into the brushy distance, Haynes cuts to a foraging coyote, its ears rigid, ready for a kill. It’s a move so naturalized and invisible—so safe—as to constitute a masterstroke, particularly in light of Haynes’s prior pattern of Freudian obviation and comparatively campy, frontal-assault satire. And while Carol clearly fits the outline of Haynes’s earlier social victims—bombarded by her environment, mold-poured into family constructions, and paddled by a series of patriarchs, she’s the latest in his series of plastic dolls—Dunning is an astonishing departure. As this fuzzy-wuzzy guru cajoles his followers into an endgame of self-blame and absolves every cultural force of culpability in his patients’ afflictions, Haynes adopts an apparently straight-forward observational mode that does nothing to contradict him, searching beyond satire to explore the desperate need for control and punishment that slowly courses through millennial America’s aging veins.

“Pride is the only thing that lets you stand up to misery . . . the kind the whole stinking world is made of,” announced Poison’s scientist before plummeting to his death. Safe inverts Graves’s epitaph. By insisting on a kind of pride (self-blame), Dunning allows his patients to fall and splatter, while his “therapeutic success” allows him—as the simple image of his majestic villa, perched high on a hillside overlooking Wrenwood, suggests—to ascend. Thriving in the underbrush of Wrenwood’s damaged drones, Dunning finally takes to the skies, not a cryptic savior like Richie Beacon, but another grubby angel, another irksome fly.

As for Carol, you hardly need notice the lesion that’s growing—blossoming—on her forehead to recognize that Dunning’s done his work and that her “recovery” is well on its way. Haynes: “What particularly drew me to want to look at the New Age philosophies of people like Louise Hay [self-help author of You Can Heal Your Life] was the upsurge of these types of treatments among young gay men with AIDS in the late Eighties. What is it about these philosophies that make the sufferer of incurable illnesses feel more at peace? Why do we choose culpability over chaos?

“So when he says, ‘Words are just the way we have of getting at what’s true,’ he turns what she’s said back into this essentialist, religious, connotative statement—and it’s not true. Words totally show you how truth is unobtainable because you can never articulate it.”

Assassins: A Film Concerning Rimbaud - 1985

Width of a Circle: Assassins, Glitter Kids

Haynes’s first film, Assassins: A Film Concerning Rimbaud (’85, shot while he was still at Brown), conjured an absinthe-stained vision of the French poet-rapscallion as a snot-nosed protopunk, marauding through turn-of-the-century Paris, spray-painting “MERDE A DIEU!” on an ivied chateau wall. Titled with reference to Rimbaud’s welter of scandal-mongering biographers, Assassins’ herky-jerky “reconstruction” of the poet’s pub-crawling nightlife and rough-trade romance with Paul Verlaine is fraught with Godardian voiceovers, fragments of Iggy Pop and the Ventures, and a variety of portentous “symbols.” I’ve seen it only once, in 1988, so my memories are a bit frosted. The only decisive note I’ve retained from the night turns on the film’s alchemical structuring principle: “In Assassins, snot turns to glitter, if not exactly gold.”

Haynes: “My next project, Glitter Kids, is a fictionalized look at the early Seventies in London and New York, with characters that reflect people like Marc Bolan and David Bowie, Lou Reed and Iggy Pop. As I research it, I see these profound connections to Oscar Wilde, and to the entire cult of personality as a longstanding result of queer expression. In both cases they made a huge impact on popular culture with these very visible images of gay sensibility. What’s so funny to me about glitter rock, though, is how the gay elements of it have disappeared over time, especially in terms of [a patently queer] band like Queen. Those sounds and styles have been adopted by heavy metal, and Queen anthems have become regular stadium songs blasted out as the epitome of macho culture. But I’m having a lot of trouble imagining making a film about something I think is cool . . . I’m a little bit nervous about making a film about pleasure.”

Beyond the contradictions and the push/pull of freedom and repression that everywhere exists in Haynes’s films, what remains is possibility: the possibility of self-expression, of fulfillment. And with each successive film, Haynes has engineered elaborate revisions on his core material, traced new ways of navigating that space between punishment and liberation. Whereas the identity concerns of Superstar (not only in Karen Carpenter’s doomed quest for her self, but in the exploration of the limits and resilience of audience identification) are fetishistic, terminal, and concentrated (on plastic figures and in plastic times), Poison seeks a cure to social claustrophobia in multifaceted approaches and open-ended conclusions (everywhere, that is, with the exception of the fatally out-of-step Dr. Graves). And just as Dottie Gets Spanked’s intensely personal and expressively uncontrollable forces seem to endlessly proliferate and mutate to the point where they all but demand repression, Safe’s subversive naturalism—where suffering is radiant and salvation a sham—only seems to offer closure and reassurance in its crushingly mannered formality and subtly caustic parody.

Where now to turn? In David Bowie’s emblematic 1972 sexual self-confrontation and coming-out-to-glitter anthem “Width of a Circle,” the diamond dog howled, “He swallowed his pride and puckered his lips/And showed me the leather belt ’round his hips/My knees were shaking my cheeks aflame/He said ‘You’ll never go down to the Gods again.’” Is Haynes, too, ready never to go down to the Gods—to forever refute containment and the forces that name us against our will? To relish his paddler and head for the stars? That way lies voluble identity and passionate hope, not to mention the pleasures of glitter rock: the preening abandon of feather boas and eyeliner, the shimmering synaesthesias of gold lame and henna, the glorious power-mad clamor of screaming electric guitars…