Interview: Gene Hackman

Eugene Alden Hackman is forty-three and was born in San Bernadino, California. His father, a veteran newspaper reporter, returned the family to Danville, Illinois, where his parents separated when Gene was thirteen. Hackman remained with his mother. When he was sixteen, he lied about his age and joined the Marines, and soon found himself in Tsingtu, China, in 1948, where he worked as a disc jockey for his unit's radio station. After discharge, he worked in a number of radio and TV stations "in the boondocks" until he moved on to New York to study acting. He married Fay Maltese, a bank secretary, in 1956, and they lived in a sixth- floor walk-up, while Hackman worked as a doorman, a furniture mover and at other jobs, while scrambling for acting parts. He made his first Broadway success in 1964 with the lead in Any Wednesday. Earlier, he won the Clarence Derwent award for his performance in Irwin Shaw's Children From Their Games, which folded after one performance.

At that performance, director Robert Rossen was impressed, and later cast Hackman in a small role in LILITH with Warren Beatty. Three years later, Beatty remembered Hackman and cast him in BONNIE AND CLYDE as Buck Barrow, Clyde’s brother; it brought Hackman his first Academy Award nomination, for Best Supporting Actor. He received another nomination in 1970, for I NEVER SANG FOR MY FATHER and won the Best Actor Award for his portrayal of “Popeye” Doyle in THE FRENCH CONNECTION.

His other films include DOWNHILL RACER, PRIME CUT, CISCO PIKE, THE POSEIDON ADVENTURE, SCARECROW, THE CONVERSATION, and ZANDY’S BRIDE. He is currently filming BITE THE BULLET, with Richard Brooks as director, and will follow that with FRENCH CONNECTION II, for John Frankenheimer. Earlier this year, he completed NIGHT MOVES for Arthur Penn. This interview was done shortly before the opening of ZANDY’S BRIDE, which was the first American-made film directed by Jan Troell, who directed THE EMIGRANTS. The interview was held in Hackman’s ranch-style home in the Woodland Hills section of Los Angeles, where he lives with his wife and three children.

***

ZANDY’S BRIDE? I don’t know. I’m the world’s worst judge of my own work, and you get very close, and I always get very involved with the director, you know, to the point where I don’t know what the hell is happening. So that sometimes, I couldn’t tell you what is good, bad or indifferent.

Jan Troell. Well, there was a language problem. He doesn’t know the idiom. He knows the language, probably better than I do, but it’s a matter of expression. Especially if you’re doing a period picture, where some of the words are transposed, and the characters don’t speak good grammar. And most of the people around a film know when something strikes the ear right in terms of that period, whether or not it’s really accurate or not. I suppose it’s not so terribly important, but he would come to a place and just have to ask: “Is that right? Why couldn’t we say such and such?” And it would be very good grammar, but not particularly apropos.

We finally got to a place where we worked quite well together, where we kind of respected each other. But I also think, besides the language problem, he is the kind of director who has a tunnelized vision of what it is that he wants; and when you are working in someone else’s country, it’s sometimes hard to communicate that. But most of the great directors, most of the good directors, have that kind of single-mindedness, that kind of purposeful attack on things. All in all, I think he’s very talented.

The first big star I worked with, seven or eight years ago, was Burt Lancaster. And I found a lot of people would defer to him in ways that—I was from the theater, you know—that I’d wonder, “Why don’t they argue with him a little bit? What, is he gonna punch them out or something?” No, not necessarily, because he’s a bright guy. But it’s just that you reach a certain level and people get frightened of your money or your power, or both, you know. And when I found myself doing that, when I found myself getting my way without somebody really pushing against me, I really started getting worried. Because I think that’s one of the really dangerous things, when you get in a certain position of being able to say just anything, and people say: “Yeah, right, bring it in.” That’s bad.

I’m consciously struggling with that. It’s easy not to do it. It’s much easier to play a little right of center, a little hard, you know, and you get your way. But you finally don’t get your way, because it finally comes back to haunt you.

I’m kind of an untrusting guy, for whatever reasons, I think probably because I had such a hard time in New York. I guess I’ve been making a living as an actor for seven, eight years—and when I say a living, I mean a pretty good living—but there was a fourteen-, fifteen-year period in New York when I was doing almost everything in the world except acting; but trying to act. And, you know, when you go through that many rejections, that much of kind of being sloughed aside, you start not trusting other people’s judgments. Because you realize that so much of what was happening to you was generalization. You weren’t getting parts just on a general level. So you tend not to trust people’s immediate reaction to your work.

It’s very confusing to me, even now, to really discern where I was then, and was I really ready to do any more than I was doing when I got there. Or could I have gotten there earlier? Or was I superseding my talents? One never knows. I keep wanting to stretch, at least within the context of my ability. But you just don’t know how much of yourself you’re using. At least I don’t.

But I was strangely philosophical about my work. Or defensive. Because I never really felt I was being held back. I built up a kind of defense that said, “If I get it, fine; if I don’t, that’s fine too.” I have vestiges of that left over. I never get too hooked on something, unless I’m actually getting ready to do it. I suppose all of us who put ourselves in the position of trying to sell ourselves have done that, in order to save ourselves. Except that I think that the guys who are really fine artists don’t do that. They really take the chance and lay themselves out on a limb and say, “Here I am. That’s the wildest thing I can do and if you don’t like it, then it’s your problem.”

Of course, that’s something you can’t really see for yourself. Something you think is middle-of-the-road may be far-out for somebody else. I don’t know.

The fame? I don’t think I really handle it; I think it handles me. Because I find myself continuing to work, and I keep saying to myself, now I’m gonna take six months off. And I have taken off for three. But even then there are projected pictures after that, so it really is handling me. And I think part of that is fear of not being asked after that next picture. Because I still believe in some of the cliches: You know, you’re only as good as your last picture; or, the public are schmucks, they’ll forget. It’s a terrible kind of energy to have to use—for your everyday life, you know? To have to worry about whether you’re gonna work again. I really don’t have to worry about that, but there is a kind of compulsion there, a kind of need to succeed, to stay at a certain level.

The body has certain mechanisms that defend you against a lot of that. You either cut out, draw a blank, pull a wall down. Or you make terrible gross errors that can’t be anything but on purpose. You know. And I’ve probably done a little of all that in the last two years. I’ve taken things I shouldn’t have, I’ve completely cut out for a while, you know, mentally. And… well, this last two years doesn’t seem like two years to me. It seems like a very, very brief time.

Gene Hackman in The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971)

I guess the audiences respond to the proletarian man they see in me: the working guy who’s doing vicariously what they would like to do. I think that’s why essentially THE FRENCH CONNECTION worked. I don’t have any illusions about my being the only actor who could have played that. A lot of guys could have. And it really is a director’s medium, as we all know. But I was the guy who played it, and I kind of reaped the harvest along with Billy [Friedkin] and some other people. But if there’s an attraction, that’s what it is. “I know Gene Hackman.” They’re able to say that, in some funny kind of way, you know, “Yeah, I know who that guy is.” And that works both positively and negatively, I think, because what it does is give you a kind of familiarity, without the mystique—which is what people are really attracted to, I think.

There’s several kinds of movie actors who are popular. There’s the kind who have the mystique. Cary Grant is a good example. I would not begin to try to tell you who he is, what he’s about personally. But I know from watching him that he’s a great actor and does what he does better than anybody has ever done. So there’s that kind of mystique. Then there’s the other end of the pole, which is guys like myself. And then there are guys who probably fall in between, who have a little bit of what I have, maybe, and also have developed a kind of mystique, through whatever it is they do in their private lives.

Sure, what happens offscreen affects your performance. Working for so many years you achieve a kind of professionalism. So that a lot of things that you are feeling through your day’s work—whether or not you are doing it on purpose or not—come through as part of the character. They give you another layer, another level, that you weren’t even aware that you were doing. As long as you are free enough to let that happen, it’s a kind of plus. It can work the other way too.

I can see a piece of film, where something was shot on a certain day, and I know that I’d had an argument with a director just before we shot, or a big laugh, and goddam, it has affected that scene in some minute way. But it added another level. And you might possibly, subliminally, feel more about that scene than was really there. That’s not the way I work. I don’t set out to find those things. But I’m very willing to let that happen, to let those layers build.

I really didn’t appreciate movies until I got into pictures myself. Until I really understood what it was to be a motion picture actor, and what it takes, and what nuances you can use, and about underplaying. I never really appreciated it until then. It was like comedy. I wasn’t really aware until my last two years in New York, when I started doing a lot of comedy, how much more expertise and real judgment it takes to do real comedy, rather than drama. Because drama in many ways is arbitrary: you can choose not to cry in a scene where everyone else is crying, and that’s a choice. And you can defend that choice to your death, saying that it’s a character who is cut off, a character who is doing a whole different number. That’s defendable. But in comedy, if the laugh doesn’t come, there’s no way you can defend that. I mean there just isn’t. You must play something that works, in comedy. It doesn’t mean you must always work in result terms. But you must make choices that are gonna create results. In drama, you can relax, you can fool around, you have all kinds of areas. You can fool around with the words in drama a lot, too. But you can’t in comedy.

I really started in the business because of Brando, I suppose. I saw in Brando some kind of kinsmanship, not because of the way he looked, but something inside him that let me say: “I can do that.” I’m sure that’s why he has such a following. People see in him some kind of strength, some kind of strength that could be an everyday attitude. Although he’s not a common man at all. He’s not your ordinary off-the-street guy. I mean, there’s a lot more to him than that.

When I first saw him in films—I guess it was THE MEN—I’d already started to work as an actor, but then that really convinced me that I could maybe do it, that maybe there really was an area for me…

In my early days as a kid, I was bananas about all the swashbuckling guys, Errol Flynn and that kind of thing. Not really understanding what it was they did, but just being attracted to the adventure. I had a terribly high fantasy life in terms of movies. I think I really had my acceptance speech for the Academy Awards when I was about twelve. But strangely, I had a real split about going off and doing something about it. Because I wasn’t in the Glee Club, or the chorus, or the community players. I was terrified, just terrified. But I still had this Walter Mitty thing in my head that said, “Oh, I can do that if I want to, but, ah, you know, it makes me a little nervous, so I’ll wait a while.” And I did. I waited until I was… oh… twenty-four.

I’m the last one who ever puts down anybody who wants to be an actor. I don’t encourage anybody. But I know from my own experience that I couldn’t have been less well equipped to be an actor. In terms of attitude and discipline, and whatever else it takes to be an actor. But I guess one’s will and determination have more to do with what you do in life than any kind of real equipment that you have. We’ve all seen a lot of actors, and other creative people, who have no talent at all, but have a great deal of will and determination, and arrive at where they want to be, because of that.

The great equalizer for me is when I go to see myself. That’s why I hate to watch myself. I think of myself as being twenty-one, twenty-two, I really do imagine that’s the way I look, because I feel that way. But then when I see myself I look like my father. [Laughs.] And the reality of that is so jarring that I just come back and be realistic…

I think one of the great tests for most actors is your choice of what you do. Your choice of what you do really reflects what you think of yourself. I think that can change. I think one can come to think more highly of oneself and elevate one’s level of performance and of character. But generally my judgment of actors, many times, depends on what they choose to do. Also of directors. If they choose to do poor material—it could be for a number of reasons, of course—it means that they don’t have a good idea of their value as a performer, or a director, or writer, or whatever the person is.

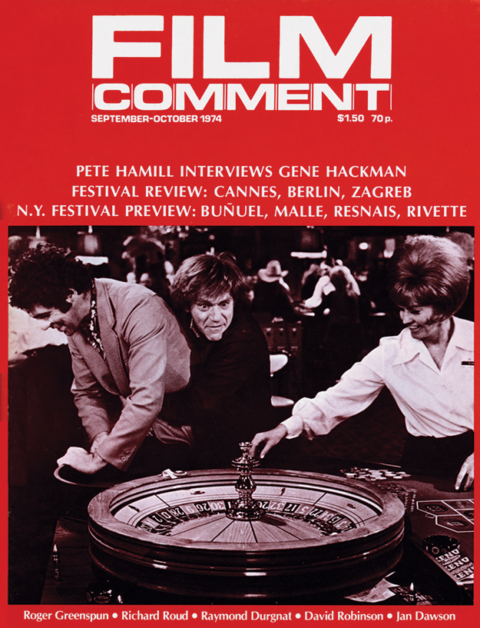

Gene Hackman in Zandy's Bride (Jan Troell, 1974)

Why did I do ZANDY’S BRIDE? I thought the relationship was not necessarily terribly unique, but it was something that was unique for me, as an actor. I think those characters have been seen before—not in that guise, not in that locale, not in all those circumstances—but they are not really that different. What attracted me was that I had never played that kind of relationship. I’d played the same kind of one-sided characters before, but never with the added thing of having some romance, and then being able to turn at the end. Or at least change somewhat, which is always kind of exciting for an actor: to be able to make some change in the character, or let the audience see some change, whether the character knows about it or not. It’s always more interesting if the character doesn’t know, but the audience sees the change.

But it’s difficult to know how much of that crudeness an audience will accept, or whether they will stay with you until you do change. Until you show them that you are a reflection of something that’s bad in them, that they would not like to see, or vice versa. It could be that you show them something good in themselves that they’ve been hiding, too. It’s fascinating to me to probe into that area, as an actor, to find out how far you can go with an audience.

One of the things with FRENCH CONNECTION that was frightening to me was to open the film beating up a black guy, using the words “s****”, “w***,” and “n*****”, you know, and… well, you start off a film in the first five minutes, laying that out for an audience, and then you say to the audience: “You’re gonna stay with this guy for two hours and you finally gotta like him, you gotta respect him, you gotta feel something for him.” That was frightening to me, and yet it was challenging.

One thing you must do if you’re gonna play a character like that is you gotta play him absolutely fucking full, so full that there’s never any doubt that what you’re saying is what you believe. If at any point in the characterization you modify him, or try to go for sympathy, intentionally go for sympathy, or intentionally delve into the heartstrings of the audience, you’re gonna get shot down. ‘Cause they’re just gonna sense that in a second. They’re gonna say, “That’s dishonest, I don’t know what it is, the guy lost me there somewhere.” And they’re often not sophisticated to know what it is that turned them off, but they’ll pick it up. Just like we do in life. We pick up on people that aren’t straight and honest with us, in some funny way. Just some strange way that we know there’s something wrong there.

I don’t work a lot on scripts. Maybe I should do more. I read them. I read them when they’re submitted to me, if there’s a deal involved, and I make a decision on first reading whether or not I want to do it. If the deal is put together, I’ll generally read it maybe six weeks later, or a month later, and generally I never look at it again until we’re ready to shoot, unless there’s a rehearsal.

The process I go through is just kind of thinking about it a great deal, almost continuously. But without sitting down and saying “Well. I’m gonna spend this next two hours here thinking about this character.” I don’t do that. I just live with it.

I never worry about lines because, after a while, at least in a feature film, there isn’t any amount of lines for one day’s work that you can’t handle. If you’re doing a courtroom scene, or an operation, where there’s a lot of technical language, and the scene went on for six or seven pages and they were gonna break it up into three or four days, but they were gonna try to get a master of that scene maybe in the first day, then you’d maybe have to do some real hard work.

But generally to me it’s kind of challenging to come on a set unprepared. I know there’d be some directors who’d go through the roof, you know. But I just like to work that way, unprepared. Knowing what the character is, but being like a sponge in some way. Being able to come on and meet your co-star or whoever you’re gonna work with—maybe for the first time—as you do sometimes in film. Or the second or third time. Certainly not knowing a hell of a lot about them. And not knowing a hell of a lot about the director, and how he works, unless you’ve worked with him before. And starting to build from there.

I generally respond to the environment. I try to, at least. But environment doesn’t seem to be as important to me as the people I work with. At least I get most of my ideas from the other people. Not that they verbalize them. But most of what I do is somehow an instinctive thing. Or it’s a bounce-back from what I’ve thought about the character, and how he would react, and what he wants to do to that other character, or what he wants to say about what the author has said.

I’m a great believer in the author’s intent. What he wants out of that scene. And what I can bring to that scene, within the context of what he’s given me to do. I like that challenge. I like the challenge of working within the box. And then being as wild as one can be within the context of that.

Generally directors are somewhat appalled that you have the script in your hands. [Laughs.] But I never start apologizing by saying, “Listen, I don’t know this.” Because then the guy’s gonna say, “Go ahead, we’ll give you an hour, we have to set up anyway, we have to set some lights, go ahead and work on it.” I never do that because I don’t want him to go away. I want to sit there, I really want to read through it and really be Mister Dummy. I want to be as blank as a piece of paper. And get it all right then, get it all from the page, and from him, and from her, and from whoever else is sitting there with us when we’re going through it for the first time.

And it really doesn’t take any more time. Because, as we all know in films, there’s hundreds of things to be done, and they’re never ready, and you’re sitting there doing your work when you’re supposed to be doing your work, as opposed to doing it the night before. And that’s how you end up with some hard idea in your mind and you come in with this great idea about the character, and this person that you’re working with also sat up all night and did the same thing. And you find yourselves diametrically opposed, you know? There’s just no way you’re gonna get together. You’re just goin’ like that and you think, well, one of us is gonna have to give. So it’s much easier, and I think much more creative, to come in not knowing. It’s not a weak kind of thing.

I’ve done it the other way, staying up all night, and what happens is you get yourself so tense, it’s like doing a speech or a public address. There are certain things you have to say, you have to introduce certain people, you have to… Well, you know, to do that you have to stay up a couple of hours and really learn that. I couldn’t do it; I’m not equipped to do that.

Gene Hackman and Lee Marvin in Prime Cut (Michael Ritchie, 1972)

When I first started to act, we used to do things like Brenner and The Defenders and Naked City, and that kind of stuff in New York, and I would maybe have only five or six lines. But man, I was Mister Tension. And I’d come on and blaaaaaaaghhhhh, God-I-hope-I-can-get-these-things-out-in-one thing so I can go home! Until finally you realize what you’re doing and you say: “Wait a minute, why do I want to be an actor if I want to go home? It just doesn’t make any sense.” So as soon as you start relaxing, the more apparent it is that the process is not one of driving against the lines, but of absorbing what’s there. I’m a great believer in relaxation in terms of any creative work. I think you can’t really think unless you relax. Acting is thinking and feeling.

Directors who think we’re tools of their vision? As an actor, I say they’re full of shit, we’re not tools at all, we have something to contribute. And yet some of the really good directors feel that way. Alfred Hitchcock: I don’t know if he feels personally that way about actors, but I know his way of working is as if an actor is there to be manipulated, to be told where to stand and what to say and get on with it.

Personally, if I were to direct, I wouldn’t enjoy that because I don’t think I have that kind of contribution to give as a director. My contribution, if I were to direct, would be the understanding of the way actors work. And my understanding of the script, my interpretation of that. That would be the limit of what I could do as a director, because I have no technical expertise. There are plenty of guys you could hire who could do that.

When I do have a guy like that, I fight like a fiend. I guess because I’ve never met anyone who I respected who directed that way. I’ve worked for a couple of directors I didn’t have any respect for who worked that way. And we fought constantly. You know, guys who had the scene completely blocked out on paper, completely thought out, along with notes and pictures that had been drawn, down to what line you would pick up a coffee cup and what line you should get up to move. That galls me to the point where I can’t work. I just don’t have the intelligence to remember all that shit. You know, I act on instinct, from years of having done it, and from ways I taught myself how to do it. And suddenly to have to rely on a guy who has thought all that out in his head, and to move on a certain line…. I can do it—I’m being facetious when I say I can’t do it—I can do it. But I really wouldn’t be comfortable, nor would I bring anything of myself to the part. People seeing it would say: “Hmmm. I don’t know why they bothered to get him.”

You can’t change a line in the theater without the writer’s permission. Whereas in films, once a writer sells his screenplay, then it’s no longer his. You can do anything you want to it. But having the writer around while you’re shooting… I don’t know. I really don’t know. I think a guy has to be super-talented and very objective about his work in order to make a contribution, once it has passed out of his hands.

If you have the Kazan-Schulberg relationship, that’s marvelous. But for a writer to work with a director without that, well, it’s just death. As an actor, you’re caught in the middle of that thing: two directors, or two writers, or half of each. You start getting ambiguous directions, or ambiguous writing. And that’s difficult for me. I prefer to work where the piece is finished, and passed on to the director—if he chooses to, and is of that bent—makes his changes as he goes along, with the help, maybe of the actors. There’s a funny kind of family atmosphere on a film that is generally created by the director. And many times that family balloon can be punctured quite readily by an outside influence, an outside force, and many times the writer is that outside force. If you’re working on a scene and you see out of the corner of your eye a foreign object, that has a head on it and looks like a writer [laughs], standing by the camera or something, I, for one, get a little tight, unless I’m close with the guy. I get a little tight. I start thinking, “Gee, I wonder if this is the way he intended this or not?” And although as an actor I prefer to work consciously with the author’s intent in mind, I know I have to make it my own.

I forget the punctuation and I never read stage directions. Unless it’s a plot point. Stage directions are only the writer’s way of getting you through the door, and over to the window, and over to the stove or whatever. And I think I can find my way over there with whatever line’s given, and whatever pauses I want to take, and whatever feelings I get from the other people, and from the atmosphere or the situation. So if I’m worried about stage directions, or I’m worried about grammar, that’s a detriment to me. And maybe that’s my own problem. Other guys can maybe work right through that. But I heard something the other night, that’s maybe pertinent. A guy said to me: “How many times have you ever heard a husband say to a wife, ‘Let’s go out tonight and hear a movie?’”

Yes, I’d like to direct. When? Well, the fame, the stardom, whatever it’s called, has given me a kind of distorted view of where I am. So I can’t tell how much time I have left. I know that in the open marketplace nobody needs me as a director. You know. I could go out and spend as much time as anyone else would take, trying to get a film to direct. So if I want to cash in as a director, I have to cash in while I’m still kind of hot as an actor. And that’s the kind of thing where I don’t know where I am yet. I would like to wait a while before I direct. But I don’t want to wait too long, to where I don’t have the juice to direct.

I wouldn’t direct to give up acting. But I’d like to phase out. I’d like to not have to stay at a certain pitch as an actor. You know, there’s a certain reality you have to face: you are a commodity; and you’re not gonna be at the same level the rest of your life; and you want to kind of prepare yourself, to be able to do other things. I’m lazy. And you know, after forty, you start backing off.