Founding Fathers

The most resonant scene in Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York is also one of the most understated. Newly recruited soldiers in the Union Army, fresh off the boat from Ireland, file onto the ship that will take them south to the battlefields of the Civil War. A hoist, bearing a single coffin, swings past them and down onto the pier, where dozens of similar coffins have already been unloaded. The sequence is a remarkably succinct visualization of war as an assembly line where live human beings are raw material and death is the product.

It’s a punishing piece of work, this Gangs of New York. Spectacular, brilliant, but punishing—basically, one long brawl framed between what must be the two bloodiest battle scenes ever committed to celluloid. At the least, the film is a corrective to the accepted notion that urban violence is a 20th-century phenomenon. “A western on Mars” was Scorsese’s original concept. In Gangs, lower Manhattan as recreated on 15 acres of Cinecittà backlot, is a claustrophobia—inducing version of the Wild West.

You don’t have to think twice about why Scorsese was attracted to this material. All of his great films are stories about New York subcultures: their origins, how they mold the individual, how they enforce their laws, the parts they play in the evolution of the city as a whole. Can the individual survive ostracism? What price does he pay for inclusion? From Mean Streets through The Age of Innocence, Scorsese has mined the dynamic between the individual and the social fabric of New York. It’s an unfailing source of drama and character for him. Taxi Driver is the counterexample—an ethnography of the ultimate outsider. In Gangs, however, the fictional narrative of revenge and romance has, at best, a forced relationship to the social history of this period in the city’s life.

Scorsese and screenwriter Jay Cocks loosely based their script on Herbert Asbury’s 1928 The Gangs of New York, an anecdotal history of the street gangs that fought for control of poor immigrant neighborhoods from the early 1800s to the early 1900s. (Cocks wrote the first version of the screenplay 25 years ago. Steve Zaillian and Kenneth Lonergan also have screenplay credits. Their work came after the film was committed to production.) Gangs is set in 1863 in the miserable, vice-ridden ghetto of the Five Points and climaxes during the Draft Riots, the most deadly civil uprising in U.S. history. The riots began as a protest against the 1863 Conscription Act, which decreed that every able-bodied man was subject to the draft unless he could pay a $300 exemption fee. As the riots escalated, class resentment was conjoined with racial hatred. The mob attacked recruiting stations, government buildings, and the mansions of the rich; they also torched black neighborhoods and beat, shot, or lynched every black person in their path. Not only did they refuse to serve in Lincoln’s abolitionist war, they were out to prove that black people had no future in New York. In the end, the many quelled the riots by shooting the protesters en masse; tens of thousands were killed.

The riots themselves and the racism they revealed (as endemic to the North as the South) operate at the periphery of the film’s narrative. Gangs’s main focus is the conflict between the Nativists (Protestant descendants of the original Anglo-Dutch settlers) and the newly arrived Irish Catholic immigrants (who, at the height of the potato famine, were flooding into New York at the rate of 15,000 a week). So intent are these enemies on destroying each other that they are oblivious to the larger historical forces about to render their tiny turf war irrelevant. Neatly burned to the ground during the riots, the Five Points had the distinction of being the city’s most blighted neighborhood until it was totally razed at the turn of the century. Paradise Square, where its five main drags converged, is now the site of the Federal Court House (100 Centre Street).

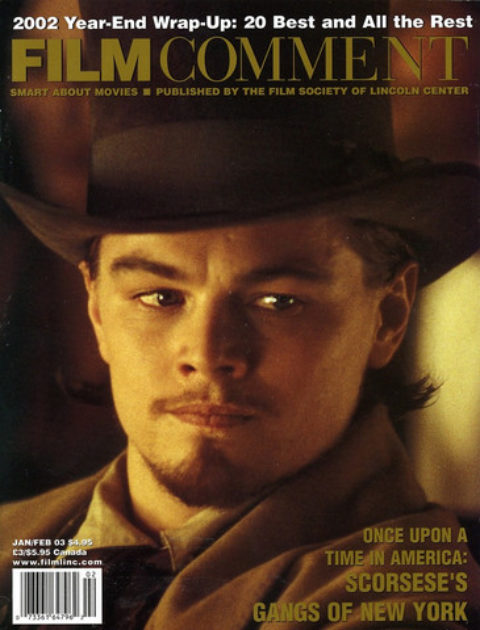

The plot on which Gangs is hung, but which hardly speaks to the film’s scope or ambition, is a familiar combo of revenge and romance. As a child, Amsterdam Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio) sees his father (Liam Neeson), the leader of the Irish gang, the Dead Rabbits, dealt a fatal blow during a rumble with the Natives by their leader, William Cutting, aka “Bill the Butcher” (Daniel Day-Lewis). Sixteen years later, he returns to the Five Points to avenge his father’s murder. He infiltrates the Natives and soon becomes the Butcher’s favorite. He’s also drawn into a stormy relationship with Jenny Everdeane (Cameron Diaz), an enterprising pickpocket and the Butcher’s former mistress. Although he doesn’t lack opportunities, he waits nearly as long as Hamlet before making a move on his father’s killer. By then, Bill has been tipped off about Amsterdam’s real identity and uses his knife before Amsterdam can pull his gun. Bill stops short of killing Amsterdam, deeming it a worse punishment that he spend the rest of his life maimed and humiliated. But Jenny nurses Amsterdam back to health, and he rises, with newfound political savvy and resolve, to unite an army of Irish immigrants against the Butcher and form an alliance with the boss of the Tammany Hall Democratic machine, William Tweed (Jim Broadbent). With his power ebbing away, Bill murders Monk (Brendan Gleeson), the moral force among Amsterdam’s supporters. A near suicidal act, it sets the stage for a final showdown.

You can read the complete version of this article in the January/February issue.