American Friends

It’s a cliché that the shock of the new tends to preclude immediate embrace and appreciation. But nowadays there’s usually at least one champion for every iconoclast that comes along. That’s certainly true for Gabriel Abrantes, Daniel Schmidt, Benjamin Crotty, and Alexander Carver, four filmmakers who, over the past decade, have quickly amassed a shared body of work that intoxicates, titillates, tickles, and scandalizes. But while this nomadic quartet of collaborators have made and screened films all over the world, their reception has often been nearly as complicated as the movies themselves.

The films of Abrantes and co. have challenged outmoded distinctions between “art cinema” and artists’ films, between work that travels the festival circuit (where it has received a mixed response) and work that belongs in a gallery (where they have been warmly welcomed). This might have something to do with the fact that these four Americans (though Abrantes is now based in Lisbon and Crotty in Paris) have, in a relatively short span of time, arrived at a cinema that’s all theirs: in which bad taste melds with deft riffs on the history of Western culture and globalization; in which irreverent humor buttresses images of breathtaking beauty; and in which an insolent surfeit of references—to paintings, novels, plays, films, and television series alike—is seamlessly synthesized with the pleasures and ruptures of the unconscious. Parker Tyler wrote in Underground Film that “the hardest thing for a very radical idea to do is stay very radical,” and they seem to have taken this to heart, committing themselves to undertaking an investigation of desire so singular that it demands a closer look before it races too far ahead for us to catch up.

A key distinguishing trait of these young, hopped-up visionaries is the unique character of their association: neither a tightly knit collective in the style of the post-’68 Zanzibar group, nor an informal network of friends (and sometimes rivals) like the French New Wave, their grouping seems more like a swingers’ party, with collaborators freely swapping partners. Of the four, it is Abrantes who has emerged as the group’s most prolific and polarizing figure. He has directed or co-directed at least 18 shorts, featurettes, and omnibus segments since 2006, a sustained frenzy of activity that has yielded an eclectic oeuvre marked by strong continuities, some of which have effectively set the terms for the rest of the group’s explorations of colonialism, culture, and Eros.

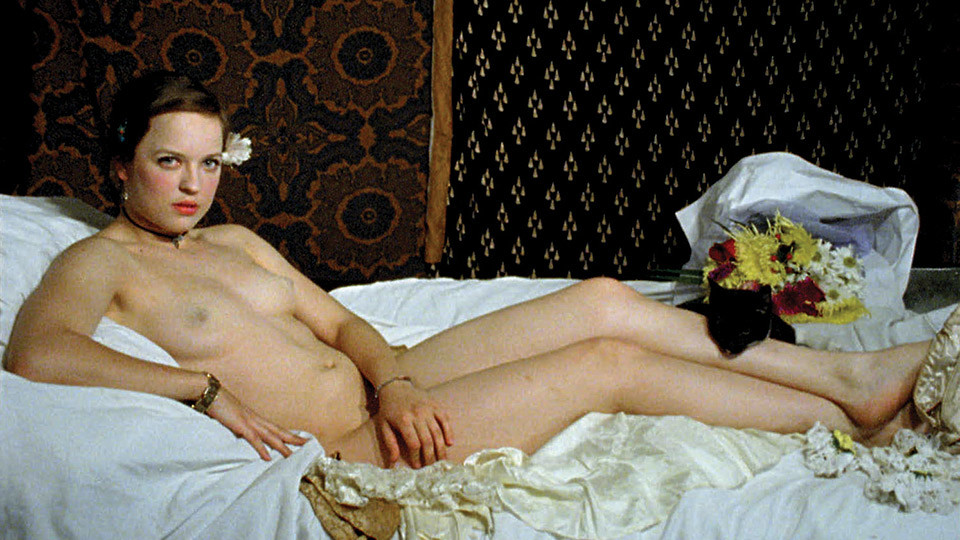

Olympia I & II

Written and directed with Katie Widloski, Olympia I & II (06) is a diptych staging of the Manet painting by the same name shot on Super 16, as is nearly all of Abrantes’s work. The first half finds Manet’s nude prostitute in repose (played by Widloski) chiding her off-screen brother (Abrantes) for being too chicken to act on his incest fantasies. “If you’re here to fuck your sister, don’t be such a pussy about it,” she taunts him, which he counters with shrill, defensive whining. The second half turns the tables, with a made-up Abrantes now playing the whore, complaining that it’s been a slow night on the job. Widloski reappears as a consoling servant in blackface, fetching him a Coke and ultimately making out with him, smearing grease paint all over his delicately powdered countenance. Unsubtle as its provocation first appears, Olympia I & II sneakily advances a moving portrayal of desire run amok and of childlike longing, complicated by the film’s curious if undigested connection between 19th-century European painting and American minstrelsy.

Most of Abrantes’s key shorts have been co-directed. Visionary Iraq (09), his first collaboration with Benjamin Crotty, then a classmate at the Tourcoing art school Le Fresnoy, is a ludicrous melodrama (in which the directors play all on-screen roles and the visual schema echoes the Kuchar Brothers and Suspiria in equal measure) concerning a Portuguese family whose naïve, incestuous children enlist in the fight for Iraqi democracy. In Liberdade (11), also directed with Crotty, a young Angolan tries to resolve transcultural differences with his Chinese girlfriend and erectile dysfunction in one fell swoop by way of a breathless Viagra heist. Fratelli (11), made with Alexandre Melo, is a Pasolinian travesty of The Taming of the Shrew that evidences Abrantes’s taste for classicism, period costume, and bacchanalia, not to mention his painterly visual sense.

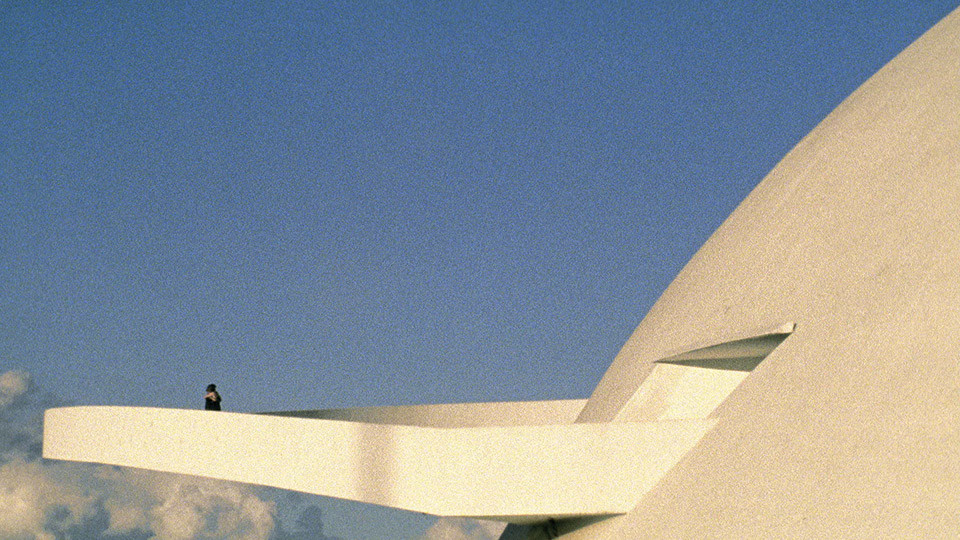

But Abrantes’s richest collaboration has been with Daniel Schmidt, with whom he directed the short A History of Mutual Respect (10) and the featurette Palaces of Pity (11). A History of Mutual Respect opens with a slow pan across waterfalls set to Nina Simone bemoaning (in an intro to a live performance of “Who Knows Where the Time Goes”) that “time is a dictator, as we all know.” The two protagonists (Abrantes and Schmidt) are young men whose search for “a love that’s simple, direct, and unmolested” leads them from the stark modernist architecture of Brasilia to a lush jungle where they both pursue a young woman. Culminating in a double-cross revealed via text message, the narrative dissolves into a paroxysm of swirling, frothy water. Abrantes and Schmidt’s characters seem to float across continents as if in a trance, their slightly stoned delivery marked by an air of automatism enigmatically suggesting a world of urges and appetites held at bay beneath the lotharios’ mellow façades. Heterosexual libido mobilizes these two buddies to scour the globe in hopes of getting their rocks off, but it also severs their fundamental bond: the incestuous couplings of Olympia I & II and Visionary Iraq have been replaced with a couple of dudes on the prowl, and competition is inevitable. Through its libidinal gamesmanship, A History of Mutual Respect seems to posit that it’s impossible to attain one’s object of desire without throwing an ally under the bus—in other words, betrayal is a precondition for pleasure.

A History of Mutual Respect

Many of the motifs and formal strategies in A History of Mutual Respect are overhauled in Palaces of Pity. It’s ostensibly about a feud between two Portuguese teen sisters following the death of their grandmother (played by Abrantes’s real-life grandmother, Alcina) and their subsequent inheritance of a palatial estate saddled with a knotty Fascist legacy, but Abrantes and Schmidt keep the exposition light in favor of supremely inventive visual play. Jaw-dropping landscapes, sumptuous superimpositions, and narcotic slow motion elevate a mise en scène littered with dog-headed lawyers, young girls decamping for abyss-like dance clubs, and, in one hallucinatory aside, sensitive knights (Abrantes and Schmidt again) weeping after death sentences are pronounced upon a pair of Moorish homosexuals by a medieval court. Palaces of Pity sets the stage for yet another incest scenario, only to subvert that expectation by instead depicting a rivalry between sisters. On the eve of and in the wake of their grandmother’s death, the ties between the siblings fray to the point of severing; one of the sisters resolves to kill herself and all of their friends by burning down the castle they’ve inherited during a sleepover, but the two wind up reconciling amid flames and smoke, their relationship repaired through arson. The erotic connection between the Moorish lovers in the film’s middle section is too pure and too attuned to their libidinal drives for their world to bear, so they are condemned to die; the sisters revive their relationship by obliterating their world. Palaces of Pity puts a new spin on the duality of creation and destruction, suggesting that both are merely different forms assumed by the erotic imagination within a dialectical chronicle of pleasure and persecution, intimacy and antagonism, lovers and siblings.

Abrantes would revisit some of the ideas explored in Palaces of Pity with Taprobana (14), his most fully realized solo work to date. It is an utterly hypnotic sort-of biopic of Portugal’s national poet, Luís de Camões, here portrayed as a zonked-out 16th-century libertine whose art will influence centuries of Portuguese culture but whose appetites banish him to Hell. Taprobana doesn’t delve into the nature of desire as inventively as Palaces of Pity, but it does find Abrantes refining his own visionary techniques for rendering it: the scene in which Camões appears before a divine jury to determine whether he’s off to Paradise or the Inferno is visually astounding, using CGI in conjunction with Super 16 to conjure an otherworldly Dantean space. Juxtaposing this with shots of Camões reclining and making love in the open air (including a scene of coprophilia that will repulse many but would likely make Georges Bataille proud), Abrantes might not dig as deeply here as in his films with Schmidt, but he nevertheless remains committed to illustrating a history of desire as the force that determines man’s fate in both the here and now and the beyond.

After completing Palaces of Pity, Schmidt teamed up with Alexander Carver, one of Abrantes’s Cooper Union classmates, who, like Abrantes, came to cinema from painting. Together they made The Unity of All Things (13), a feature-length, science-fiction-inflected dissertation on yearning that rates among the group’s very best and most visually accomplished works. Shot with a patchwork of Super 16 and Super 8 in opulent locations in China, Switzerland, and the U.S. (including particle colliders in Beijing, Geneva, and Long Island), the film’s narrative follows a group of physicists involved in the construction of a new accelerator on the Mexican border. The Unity of All Things is replete with startling and ravishing conjunctions of image and sound, darkness and light, the sea and the stars: balancing its cosmic sense of scale with an unwaveringly dreamy atmosphere, the film argues for desire as the metaphysical ground underlying all phenomena—including that which belongs to the supposedly objective domain of science.

The Unity of All Things

The incest theme is refreshed in The Unity of All Things through Schmidt and Carver’s simultaneously sensual and cerebral approach. The brazen portrayal of sexually involved siblings that marked Olympia I & II and Visionary Iraq is reconfigured as a tender, almost innocent attempt by the lead scientist’s sons to reconcile their internal contradictions (suggested in part by their being played by women) and figure out what exactly their bodies want, in order to decide whether to own the taboo or renounce it. Thus, the film curiously ends up being a kind of coming-of-age tale centered on the acquisition of sexual identity in parallel with quantum physics’ quest for the fundamental truth of matter.

Schmidt and Carver followed The Unity of All Things with The Island Is Enchanted with You (14), a 28-minute nonnarrative meditation on the ties between colonialism and carnality. This work, which exists as both a film and a two-channel video installation, collapses together a vision of imperialist exploitation and libidinal revolt in 16th-century Puerto Rico with a host of arcane theses about the emergence of public health campaigns in the 19th century. But The Island Is Enchanted with You intends to arouse rather than lecture; it features copious slo-mo, mystifying CGI, an island capable of speech, and a musical interlude set to reggaeton singer El Joey’s “Fantasia Sexual” that may be one of the most unexpected and delightful moments in recent cinema. Unlike The Unity of All Things, this film avoids making a grandiose statement about desire, despite its self-consciously heavy use of loaded signifiers (contemporary pop music, period garb, etc.). Instead, it is an immersive, historical snapshot of the pleasures Western imperialism and exoticism has sought through contact with foreign beings, places, and forces, and the complicated consequences of those encounters.

Following his own collaborations with Abrantes, Crotty went solo for his debut feature, Fort Buchanan (14). This sui generis homefront soap opera chronicles the sexual intrigues among a makeshift community of randy husbands and wives living in the woods outside a fictitious U.S. military base in Alsace. Roger (Andy Gillet, of Eric Rohmer’s The Romance of Astrea and Celadon) is struggling to raise his teenage daughter, Roxy (Iliana Zabeth, who was in Bertrand Bonello’s House of Tolerance, as were several of the film’s other actresses), in the absence of his husband, Frank (French soap star David Baiot), who is stationed in Djibouti. Roxy is eager for sexual initiation, which two of the service wives, Pamela (Pauline Jacquard) and Denise (Judith Lou Lévy, also the film’s producer), compete to carry out. Meanwhile, Justine (filmmaker Mati Diop, a classmate of Abrantes and Crotty at Le Fresnoy) has her eyes on hunky Guillaume (Guillaume Palin), willfully disregarding his preference for dudes. This ensemble eventually takes a by turns leisurely and chaotic trip to visit Frank, followed by a melancholic final act that details the soldiers’ return home and the closure of the base.

Fort Buchanan

Fort Buchanan is both emotionally astute and seriously funny, and draws upon an eclectic constellation of references: Rohmer films, reality shows, and episodic television (Crotty sourced and collaged nearly all of the dialogue from a vast archive of teleplays). Crotty expands upon the exploration of libidinal forces by Abrantes et al. by recasting it as burlesque, at once silly and sincere, built atop a complex pop-cultural matrix. Fort Buchanan suggests that our understanding of desire is nothing more than our familiarity with its cultural representations—that its truth is a matter of artifice and reference. Postmodern, for sure, and yet no less moving for being so.

The gang’s forthcoming projects—a collaboration between Abrantes and Ben Rivers, entitled The Hunchback; a long-gestating feature co-directed by Abrantes and Schmidt; a feature-length tale of forbidden love to be co-written by Crotty and experimental filmmaker James N. Kienitz Wilkins (another Cooper Union alumnus)—promise to further enlarge the scope of their shared project. While it may be difficult for a radical idea to remain radical, these four filmmakers have already demonstrated that they have enough tricks up their sleeves to keep things very interesting from here on out. Their admirers and detractors should consider themselves warned.

Dan Sullivan is the assistant programmer at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.