First Look: The Lady and the Duke

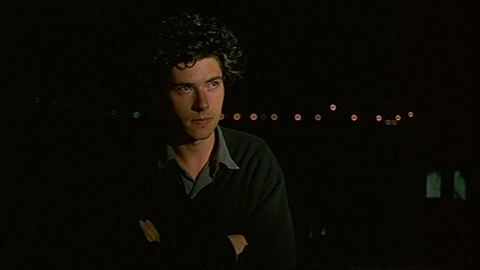

Here’s a film that will raise a few eyebrows. Having completed the “Tales of the Four Seasons” cycle with the estimable Autumn Tale, Eric Rohmer returns to the genre of costume literary adaptation for the first time since The Marquise of O (76) and Perceval (78). These two readings of literary classics (by Heinrich von Kleist and Chrétien de Troyes, respectively) are extremely stylized, one along the lines of a theatrical miniature, the other based on romantic painting. Both films broke with the conventions of cinematic period reconstruction in order to emphasize the idea of representation. Twenty-three years later, Rohmer has used the hitherto completely unknown and perhaps apocryphal journal of Grace Elliott, an Englishwoman who lived in Paris during the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror, as his source material. The film takes place from 1790 to 1794, and depicts the Revolution from the point of view of Grace, a foreign witness who’s not completely hostile to new ideas but is horrified by the execution of King Louis XVI, and by the tilting of the balance of power towards the Terror, and its extensive use of the guillotine and mob rule. Rohmer has grounded the story of Grace (Lucy Russell) in her relationship with the Duke of Orleans (Jean-Claude Dreyfus), her friend and former lover. Cousin of the King, Philippe d’Orleans was known for his lofty ideas (earning him the nickname Philippe Egalité) and for voting in favor of his father’s execution; he himself would eventually fall victim to the Terror and die on the scaffold. Grace undoubtedly survived due to her ties to the Revolution’s liberal English sympathizers, and also because she was possibly a double agent (a theory Rohmer himself proposed in a recent issue of Cahiers du Cinéma).

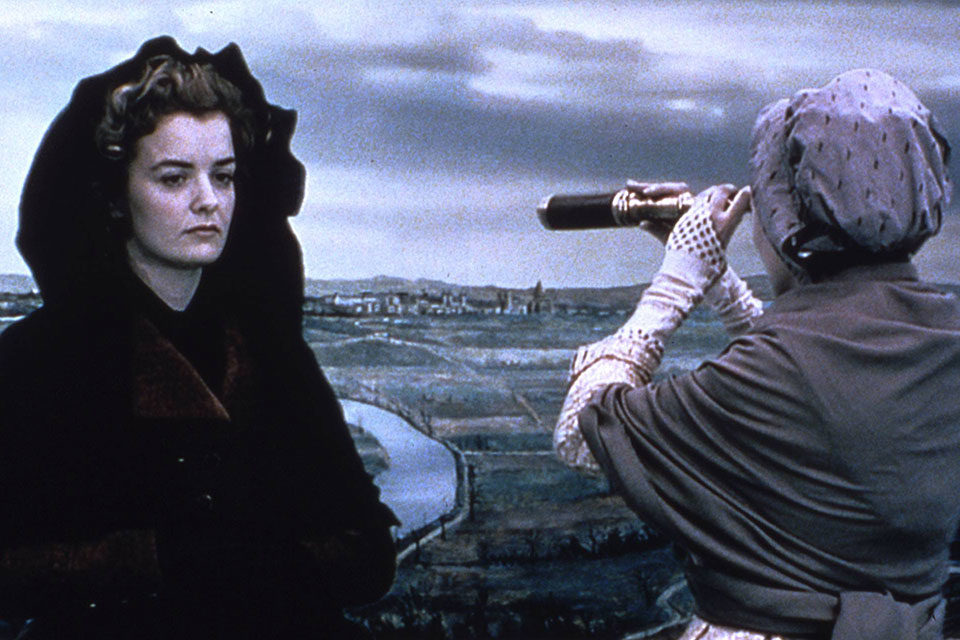

If the material is unusual for Rohmer, its treatment is even more so. Always considered the most Bazinian of the Nouvelle Vague directors, he here turns for the first time to digital video—his first foray into the format aside from La Cambrure, a 17-minute film presented at Cannes in 1999. Even more startling, instead of constructing expensive sets, Rohmer, whose sense of economy has become legendary, shot the film’s exteriors on blue-screen backgrounds and superimposed the cast onto painted tableaux inspired by 18th-century engravings. The results are spectacular, recalling early cinema projection techniques and 19th-century magic lantern presentations, as well as the panoramic views of Venetian painting, the canvases of painters like Hubert Robert, and children’s slide shows and shadow play, with vague silhouettes seemingly floating against exterior backdrops. The film’s long interior dialogue scenes, shot on traditional sets, are less convincing. Here, the mise-en-scène becomes almost televisual (albeit high-class television), with a flat, unidimensional naïveté and bloodless characters. Though Lucy Russell is remarkably subtle, Jean-Claude Dreyfus’ willfully outré performance—he accompanies every line with a sigh or a raised eyebrow—contributes to an overall sense of artificiality. On a theoretical level the film is completely fascinating. Rohmer clearly wanted to create a stylistic antidote to the bloated period superproduction with its false realism, while pursuing a primitive dream of silent cinema and its organization of cinematic space.

But the film on some level is a little disappointing—you may tire of following these characters and their political and amorous intrigues. Strangely for Rohmer, The Lady and the Duke is devoid of humor and a little lacking in sexual voltage. It’s as if, overwhelmed by technical concerns and the challenge of making a high-budget experimental film (it is the director’s most expensive production), Rohmer didn’t know how to maintain a critical distance from his characters. Usually he follows his protagonists as they incessantly tell themselves stories, all the while pointing out their hesitations and illusions. Here, however, he accompanies Grace body and soul, face to face with History. She is depicted as insight and fidelity personified in an era of betrayal and blind violence, a too-sublime heroine who lacks even the slightest psychological complexity.

The Lady and the Duke is also a political film. A right-leaning director, who has never made a secret of his conservative, even reactionary, views, Rohmer plainly regards the French Revolution as the beginning of the end, a decisive step towards a now-inescapable barbarism. Relishing this opportunity to have it out with French historiography in general, and Renoir’s La Marseillaise in particular, Rohmer has forgotten the old Hitchcockian adage: “The more successful the villain, the better the film.” This should hardly come as a shock, since Rohmer’s films don’t usually have villains. Although his justification is that the film adopts the point of view of an Englishwoman who dreams of a constitutional monarchy rather than a people’s republic, his treatment of the sans-culottes, the revolutionary tribunals, the people of Paris, and even the unlucky Philippe Egalité, is too unambiguous to be dramatically effective. “Next to this, Sacha Guitry is Karl Marx!” a Parisian critic whispered to me during the screening. The strange thing is that Robespierre is portrayed sympathetically as a man of moderation during a brief scene in which, thanks to his intervention, Grace escapes her accusers’ iniquitous and bloody claws. Its heavy anti-revolutionary thrust is too obvious to overlook; but nonetheless the film has beautiful moments in which characters come alive again. And there’s also Rohmer’s delight in the possibilities that his virtual engravings afford him to play with space, and to emphasize the personal sphere’s separation from or reconciliation with History—as in the magnificent sequence where Grace observes the King’s death from her terrace at Meudon. But these grace notes can’t quite dispel the sense of distinguished ennui that hangs over the film. The Lady and the Duke remains a partially successful prototype by one of France’s most adventurous directors.