Flow Through Me

At Eternity’s Gate is a portrait of Vincent van Gogh during the last and most prolific years of his life. It is directed by Julian Schnabel, himself a painter, and stars Willem Dafoe. The film is so much a collaboration that I hesitate to designate it Schnabel’s alone. Together, Schnabel and Dafoe, who is in virtually every frame, have made the first convincing and illuminating non-documentary film about what great painters do and how they see, and for his efforts, Dafoe won Best Actor at the Venice Film Festival. Since 1980, he has appeared in over 100 films and has been nominated for three Supporting Actor Oscars. He began in the theater as a founding member of the experimental company The Wooster Group. While bringing the group’s physical approach to character to his screen work, he has never fallen into staginess. His characters, of which van Gogh is among the most visionary, inhabit the screen as if it could be a portal to infinite possibilities for transformation and for touching the real.

At Eternity's Gate

I was looking at an interview we did in 2000 around E. Elias Merhige’s Shadow of the Vampire. You were explaining what you do when you act. You said: “My impulses are the impulses of a child because I like being the thing itself. My real pleasure—where I feel vital and everything drops away—is when I’m in the middle of doing it, and I look for that pleasure untainted by other responsibilities. That doesn’t mean I’m not analytical or that I’m anti-intellectual, or that I have no technique. But it’s a pleasure to borrow someone else’s body and someone else’s life. That’s the craft and a little bit it’s voodoo.”

That’s a good quote. I could stand by it now. People always think pretending is a bad word. I think it’s a good word. Do you remember [the Hungarian experimental troupe] Squat Theatre? I remember someone asked one of the Squat Theatre actors how he would describe their acting style. He said, “We play cops and robbers. I play cop, he plays robber.” It alludes to children’s games. You have the will to take another shape or take on someone else’s experience. The difference is that now you’re a 63-year-old guy who has a certain perspective on life and is still trying to figure things out. And that can’t get tossed away. So the only thing I would add is I am like a child, but a child who has preoccupations. As you get older you can’t deny a certain history of experience. These dialogues that van Gogh has in the movie are evocative for me. They speak to me.

I was thinking about the relationship between your process and van Gogh’s process of painting, how he was most present when he was in the middle of doing it.

I think everyone wants to be in the swirl, and I use “swirl” because that’s what he painted. He stops thinking when he’s painting. It’s not only a meditation. It’s a meeting with something greater than him. That’s a spiritual impulse, that’s a confrontation with the basic thing of being human, which is how we deal with this fact that the second we’re born we’re dying. Just fundamental things, but it’s expressed through concrete acts. It’s not opinion, it’s not idea, it’s really a series of actions, like a dancer, like a workman. He said, “Christ is a workman.” He did.

Did you read a lot of van Gogh’s writing?

Yes, it’s very beautiful. He was very sincere and very committed. Making the movie, I was less interested in his pain than in his ecstasy, which he does express. The time period of the movie is when he was very ill but also most engaged.

Mentally or physically ill?

Both. I don’t know the degree of his mental health. I can only guess from his letters. But what you can know is that he was crazy prolific. He was engaged and he was turned on and he was doing what he wanted to do.

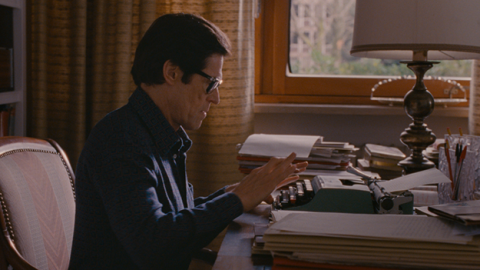

At Eternity's Gate. Photo: Lily Gavin/CBS Films

When you say you were more engaged with the ecstasy than the anguish, still for me the most moving moments in the film have to do with his feelings of abandonment. When Gauguin [Oscar Isaac] tells him he’s leaving, or when his brother Theo [Rupert Friend] visits him in the hospital and Vincent curls up in bed on Theo’s chest, those are the indelible moments. That’s what makes Vincent human and not just some famous, weird painter.

It makes sense that you say that, but, once again, I’m dealing with the painting. With Theo, that’s a very visceral thing—two grown men in bed in an asylum, holding each other, and Vincent saying, “Don’t leave me, don’t leave me.” So it’s not like I was asleep during that. But those moments kind of play themselves. And similarly, in that beautiful space in that park in Arles, just physically to run out there and have Gauguin leave, it plays itself. I don’t have to invest it with the pain of abandonment. The abandonment is there.

You mean just by being alone in that space?

Yeah, and that I’m in every frame of this movie. So there’s the sense of [Vincent] being the motor and things going in and out of his life. It is a different experience when Oscar and Rupert are around. When they’re gone, I’m left alone with just Julian and the crew. [Laughs] In very cold Arles. We were shooting in November in Arles. And of course we were wearing these period clothes, no Gore-Tex underneath.

The first words in the film are spoken by you in voiceover. Vincent is wondering what it could be like to be an ordinary person.

Just a member of the community. It’s the social thing and it also involves function. He says, “I want to be one of them, I want to have some cheese, and I would make a painting, and they’d take it and they’d smile.” It’s like functioning socially at a very simple level.

The Last Temptation of Christ. Photo: Universal/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

You’ve played great characters on the two extremes, saints and visionaries on the one end and pure evil on the other. You played Christ in Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ and you also played the terrifying Bobby Peru in Lynch’s Wild at Heart. But you’ve also given performances that are equally memorable as the movie’s “ordinary man,” like the motel manager in Sean Baker’s The Florida Project and the detective in Mary Harron’s American Psycho.

And in [Paul Schrader’s] Light Sleeper, I was also the normal guy.

So is your process different when the characters are extreme from when you are down the middle?

You don’t make those distinctions, but your job is always different. I’ve never been involved in an industrial product. I’ve been in films that were tainted by that, but going in that was never the idea, or at least I didn’t frame it that way. So when I go in, I say, what are we doing here, what do I have to do to make myself available and be in the mix. One thing I’m reflecting on right now is how people talk after a movie [is finished] about who did what. Our ideas of how movies are made are so rigid. The truth is there is so much overlapping of responsibilities. In the best situations, like this movie, there is great fluidity of who does what. It’s collaboration. People think there’s a script and you interpret it and put it on its feet. But in the best situations for me, it’s all the stuff around those pillars that’s the best part of cinema. It’s the poetic moments I love.

But to go back to your question: you start by asking what’s happening here and where do we drive this. You look around to see who you’re with, and it’s always different. And I love that because you don’t go to the same impulses, and you have more possibilities to be transformed. To leave your habits and patterns of thinking behind. And that’s the most powerful thing movies can do. They can change your mind and remind you of things you’ve forgotten. They can affirm or bring you back. I really think the comfort in movies is that they challenge you. My favorite thing is to leave a movie feeling such deep empathy—and this sounds kind of Pollyanna—that you say, I’m going to change my life. Or I’m going to be nicer to that nasty fucker at the local store who always gives me a hard time. That’s engagement, getting outside yourself in a way that makes life fun.

I saw At Eternity’s Gate twice and it was a different experience each time. The second time I was too close to the screen and I started seeing the camera movement as a thing in itself rather than a way to see through van Gogh’s eyes. But the first time I was reminded of a Wooster Group video that was used in Frank Dell’s The Temptation of St. Antony, where the cast goes to a motel and seems to, or more likely actually does, go on an acid trip. And there’s that text about everything being a chemical reaction. And how delusion and inspiration are so close. In any case, this movie brought me back to an earlier experience of altered vision, which I sometimes also experienced as an actor. I wonder if you had any memories of that Wooster Group piece, or if your connection to that kind of change of consciousness came into your portrayal of this painter, who probably had some kind of brain chemistry changes.

I didn’t think about that particular play in relation to the movie. Van Gogh did drink absinthe, but I didn’t want to dwell on that. I didn’t want to make him this drunken genius. But am I interested in changes of consciousness? Yes, of course. I’m interested in transformation and coming to clarity. As I get older, life is all about seeing behind the veil. To be able to accept impermanence as a beautiful thing. Particularly in a society that conditions us to be armored. As an actor, you get opportunities to have glimpses of that, but how you sustain the glimpses is life work—what kind of spiritual practices you have and how you conduct yourself in the workplace. As I get older, the need to connect to those things is more urgent.

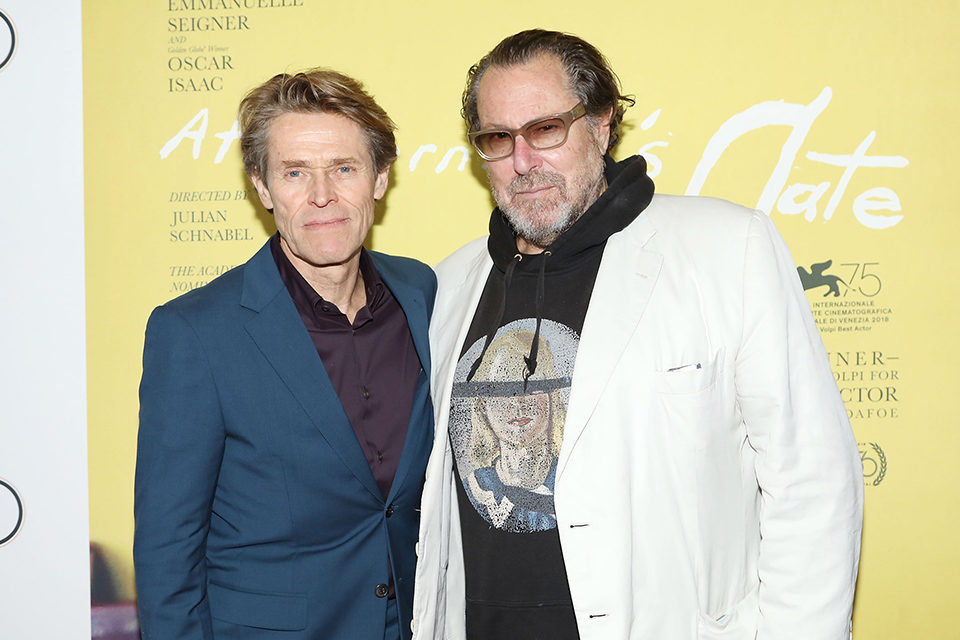

Willem Dafoe and Julian Schnabel at NYFF56. Photo: Patrick Lewis/Starpix for CBS Films

Could you talk a little bit about your relationship to Julian as the director?

He’s an artist. I’ve known him for 30 years. I’ve known him socially and I know how he works in his studio. He painted a portrait of me. The artists I like to be around have a way of collecting things, bringing them into a room and ordering them, and creating relationships. That’s basically what he does, and his films are not any different. He collects these things that he’s attracted to and puts them together to see what happens. He’s a curious guy, and he’s an artist in the sense that he makes things that reflect his experience, and he has these tools to express that. And of course, the movie is about painting, but he can’t be the painter. He doesn’t look like van Gogh. So I have to paint for him.

And I love being his creature—the creature of someone else’s impulse. Some people think that sounds terrible. “You don’t like to express yourself? That sounds so passive!” But I think there’s great power that comes from submission and losing yourself, because then you aren’t protecting anything. And you really have the possibility to see things that normally you couldn’t see. I love that relationship. So you have a strong personality that has great need, intelligence, and hunger, and I’m kind of sent out as the explorer. And with my body, I make myself available to these experiences and they’re reported. And I want that stuff to work on me and change me. That’s a beautiful relationship.

So Julian basically gave me all these beautiful opportunities. Not only to paint, not only to see in a different way. He has a concept of making marks [on canvas] that make things come together in a different way. I’ve seen that. They made a lot of van Gogh copies, probably a hundred. Many of them were very good likenesses. But he’d see them and he’d say, “Let me work on this.” And we’d get out the paint. He’d also illustrate things and he’d bring them alive with marks. And I was in the mix with that. I was making marks. And I was painting the light, which was the other big revelation. You don’t see a tree, you see the light, which also puts you in a different way of seeing. I’m not talking just about eyes, but understanding the rise and fall of phenomena. You have a concrete way to experience that. That’s pretty thrilling. That’s not being asleep.

So you would say the same thing as 20 years ago. You have no desire to direct?

No, because I imagine the director has a certain kind of responsibility. I’m very responsible as a person and in my role as an actor, but the director has to point things in a certain way. And whenever I’ve had to do that, I start to recognize things, to name things, and I get away from the experience. Also, I don’t like telling people what to do. Not that I’m a great guy… I just don’t know what I need until I get there. For example, when Julian gets to a place, if there’s a structure he’ll dismantle it because he has to feel himself. Me, I embrace that structure because it frees a part of me to do something rather than reflect on the structure. That’s the difference between the doer of the actor and the watcher of the director. I’m a doer and a dancer and an athlete more than a framer, a director. There are overlaps but that’s basically my personality.

Closer Look: At Eternity’s Gate opens on November 16.

Amy Taubin is a contributing editor to Film Comment and Artforum.