Fever Pitch: Sicko

Imagine yourself as a moviegoer of the old school, dropping into theaters according to your own schedule and not the showtime. Here is some of what you’d see and hear midway through Michael Moore’s Sicko, in the time it would take to grope your way to a seat:

A young man speaks to an unseen interviewer about the college debt he’s amassed, then is replaced onscreen by hustling figures who seem to have come from an old industrial film. Or are they the background characters in a noirish thriller? Their maniacal labor breaks off, as a pinch-faced man in a business suit suddenly looms in the shadows of an office doorway. A sneering wiseguy looks up at him from a desk and says, “Of course, if you don’t like this job, you’re always free to leave.”

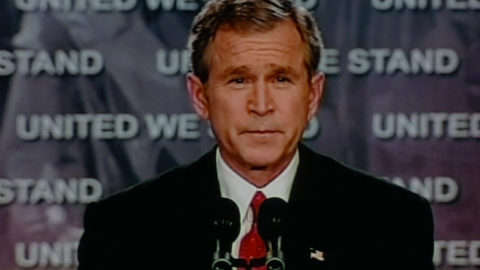

“I have three jobs,” interrupts a pleasant-looking woman. She is smiling at President George W. Bush, who sits next to her at one of his town-hall photo ops. (No town, no hall, but an appreciative studio audience.) “Do you get any sleep?” Bush rejoins cheerfully—at which point drug-company ads come rushing forward, like a deck of cards riffled at your face. “Yes, ask your doctor!” cries the voice of Michael Moore. Charlie Chaplin squeezes into the corner of a little room, watching as a health-spa practitioner mangles some client. On the floor, an elderly charwoman from a different silent picture lies raglike, until a boot comes into the frame and kicks her.

Sicko

“And don’t forget,” booms Moore, as the scene changes to a view of fresh rubble in Iraq, “defeat the terrorists over there, so we won’t have to fight them here!” If you were to walk in without preparation on this furious montage, you wouldn’t know whether it was a delirium or an argument, a digressive frolic or a stab at the heart of the main topic. But to quote the greatest of Moore’s faux-naïf predecessors, Huck Finn, “that ain’t no matter.” You could watch Sicko from the beginning, three times over, and still this sequence would escape definition.

I find that amazing—because this is a movie that everyone can describe, without even entering a theater.

Universal knowledge of Sicko dawned on May 10, 2007, nine days before the premiere at Cannes. On that date, the Associated Press reported that the U.S. Treasury Department would investigate a trip Michael Moore had taken to Cuba while making his new film. With that, a subject was announced: the ills of the American health-care system. The expected tone was confirmed: satirical and prankish. (Moore had gone to Cuba with a group of rescue workers—veterans of the emergency efforts at Ground Zero—to get them the medical care they had not received in the States.) For those who read to the bottom of the AP report, even the marketing strategy was revealed. The wire service said it had recently obtained a copy of the dot letter. From whom had the document been obtained? No imagination was needed.

Sicko

The next day, Moore stepped forward with two Internet postings. On his website, he published a copy of the dot letter, so that everyone could share in what the Associated Press had seen. To spread the news further, he also went onto the political blog Daily Kos, making public a letter of reproach he’d just sent to Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson. Out rolled the follow-up articles: seven in The New York Times alone (not counting reports from Cannes) before the end of May.

Granted, the dot had willingly furnished this publicity, earning Secretary Paulson his thank-you in Sicko’s closing credits. But if this promotional opportunity had not arisen, surely a different one would have presented itself, or been provoked from another sucker willing to tape “Kick Me” to his own behind. Moore loves guerrilla media tactics, both in practice and as a subject to document on film, and seems to recognize little distinction between the two. In Sicko, he shows how he used his website to gather medical horror stories for the movie (and to recruit onscreen talent). He even recounts how a Mr. Noe, previously unknown to him, threatened to sic Michael Moore on his insurance company, and so won approval for his daughter’s surgery.

Put yourself in the mind of an old-school moviegoer, and you won’t find anything surprising in this salesmanship. There has never been a clear boundary between making a Hopalong Cassidy movie and a Hopalong Cassidy lunch box, a Disneyland park and a Disneyland television series. Do these examples seem inappropriately cheap? Then consider a first-rate director who was something like Moore: a portly man of Catholic background, often teasing in manner but obsessed with the violence in everyday life. Alfred Hitchcock crafted his personal image and his marketing as meticulously as he made his films.

Sicko

In none of those three areas could Moore have taught anything to the master. What Moore can do—and has done notably in Sicko—is to create a special case within this history of cinematic self-promotion. In part, his marketing efforts stand out because they’re political in their goal and not just mercenary. Mostly, though, they’re exceptional because the work itself now threatens to confound them.

What kind of a movie is Sicko? The question echoes beyond the little circle of critics, with our mania for classification. People argue over whether to call it a documentary, an essay, a polemic, a piece of agitprop, or a work of performance art, because each name asserts something different about the film’s relationship to truth.

Everyone knows what Sicko is about—but once in the theater, nobody (myself included) can define what’s on the screen.

Sicko

So let me start again, this time from the beginning: When you think through Sicko in its entirety, you can see it’s as structured as a term paper. Moore has organized it into four large sections, each meant to prove a thesis:

1. Even when Americans have medical insurance, they may suffer financial ruin because of illness, or lose their lives because the insurance company won’t pay for needed treatments. This is not an accident. It’s how the system is designed.

2. Powerful interest groups, working in concert with the political class, have put this system in place for their own benefit. They don’t want it to change.

3. In other nations, democratic action and a sense of mutual responsibility have created a better system. Canada, England, and France have well-functioning national health services funded by the taxpayers, and no one (not even the doctors) suffers because of it.

4. What those nations can do, we can do, because we have our own tradition of generosity. See how the rescue workers helped people at Ground Zero. Now that some of these workers are sick, surely we, as a society, ought to help them in turn.

Al Gore could present this outline on PowerPoint. As you watch Sicko and remark on its sometimes bumpy transitions, you may sense that it’s clicking through the items on a list; and soon enough, on Moore’s website, you may expect to find footnotes for them, just as point-by-point references are now posted for Fahrenheit 9/11 and Bowling for Columbine. On this level, Sicko conforms to the standards of what most people mean by “documentary.” Of course, Moore’s antagonists (I understand there are a few) will challenge each assertion he makes; but the worst that can reasonably be said about him is not that he lies in making his argument, but that he omits.

Sicko

For example, in his account of how managed-care companies took control of American medicine, Moore correctly tags Richard Nixon as the great enabler of the HMOs. He doesn’t mention that organized labor supported the Nixon initiative. In his account of how Hillary Clinton tried and failed to reform the health-care system, he correctly portrays her opponents as angry white men, determined to slap down an uppity woman. He doesn’t mention that her proposals had nothing to do with tax-funded, single-payer health care. When Moore goes to France, he asks whether its middle class lives well despite the high tax rate, and he answers, correctly, that they do. He doesn’t ask about the relationship between their privileges and the chronic unemployment in the banlieues. When Moore goes to Cuba, he asks whether its medical system generally serves the population well, and he answers, correctly, that it does. There’s a lot more that he doesn’t ask.

Omissions such as these may open Moore to criticism; but none of them, I think, invalidates the point being made. Their main significance, in terms of filmmaking rather than policy wonkdom, is that they allow Sicko to jounce along briskly, without the back-and-forth rhythm that comes from a lot of yes-buts. I think this same concern with pace justifies an even larger omission: Moore leaves out all explanations for America’s health-care problems other than his own. At the very beginning, he does bring up one of the most prominent of these alternative explanations, as put forward by George Bush: the notion that malpractice lawyers are the main culprits. But the mere fact that Bush makes this claim is reason enough, in Moore’s eyes, to assume that the audience will find it risible. Sicko drops the matter at once, and (fortunately) never returns to it.

So much for the missing evidence in Sicko. What sorts of things are included? Here’s where the documentary category really breaks down. The trouble for Moore (or the glory) is that even though he takes pride in building a logical case, his instincts as a filmmaker draw him toward types of evidence and styles of argument that have little to do with logic. He’s like a man who opens the neatly alphabetized drawers of a filing cabinet and pulls out a pair of pajamas, a children’s storybook, half a roast beef sandwich, and a live hen.

Sicko

His primary evidence is not so much anecdotes as people—a gallery of messy, idiosyncratic humanity. Some are simply interviewed, as on a television newsmagazine. They give heartbreaking testimony, or spin out ideas for Moore (as does the U.K.’s Tony Benn, the grand old man of Old Labour). Other people go further, providing home videos and family albums to edit into the montage. A few let Moore into their lives, permitting him to record the sort of direct-cinema segments you might find in a Kartemquin Films picture, or even something by Fred Wiseman. And a handful become full collaborators, in effect portraying themselves in scenes Moore has contrived.

This isn’t just variety—it’s unruliness of the most admirable kind. Even in the most straightforward interviews, Moore’s people overflow the explanatory purpose to which they’re put.

A lesser category of evidence is archival footage: videos of Congressional hearings and presidential speeches, vintage newsreels, a section of Nixon’s White House tapes, even a ripe example of the Soviet farm-labor musical. These audiovisual documents have basically two purposes in Sicko: to convey information, or to mock. (Moore seems to believe that old moving images inherently come off as ridiculous, even when they show John F. Kennedy explaining a genuine threat.) But even though the function is diagrammatic, the experience again is unruly.

Sicko

Threading its way through this crazy quilt, piecing it together and explaining how it makes sense, is the film’s third component: Moore’s voiceover. You are aware at all times in Sicko of being guided through the subject by a public figure, and like most such people, Moore often sounds phony. Perhaps, despite being aware of his own eminence, he doesn’t realize he can no longer play Huck Finn. Or maybe the clinkers are a deliberate send-up: the gentle chumminess, the aw-shucks wonder, the italicized ironies could all be a parody of Ronald Reagan. Either way, Moore’s voiceover adds another layer of paradox to Sicko. It sounds sweetly reasonable and puts you on guard.

You’ve seen the Oscar speech. You’ve browsed the website. You know Michael Moore is not just compassionate, sorrowful, and funny, as he usually tries to seem in Sicko. He’s also angry, with good reason, and doesn’t much mind being unfair. So once more, what you encounter in the film conflicts with what you know from outside. This tension may energize the experience; it will very likely amuse you (assuming you’re not one of his chronic antagonists). But it will leave you even more confused about the kind of film you’re watching and its relationship to the truth—until you get to that college grad with his debts, and all hell breaks loose.

Whether it’s delirium or argument, digression or direct attack, that sequence dispenses with Moore’s usual voiceover guidance and turns his words into harsh, discontinuous outbursts. The visual takes over—and what this brilliant setpiece gives you, as effectively as in any film since The Crowd, is a vision of modern life as anonymous, dronelike despair. This is the essential ill that Sicko addresses, in an eruption that’s the most unruly and uncategorizable part of the whole movie, and the most unmistakably heartfelt. You want the truth? Moore can handle the truth.