Festivals: Trolling the Croisette

Cannes began one day early this year, but it might as well have been one week longer, or one month. The festival can feel like it’s been happening for ages before it’s even started, thanks to the anticipation of the lineup, the ceremonial unveiling of the lineup, the ceremonial evisceration of the lineup, and of course the pronouncement of the entire festival as dead and ready for the slab long before anything has even screened.

The process is partly foreseeable for an institution with such an outsized reputation—live by the sword of fame, die by the sword, you might say—but amid the noise, it’s worth distinguishing between the opportunistic or lazy hype and the legitimate cases for improvement. For example, you might hazard a guess that companies basing their business model on customers viewing movies at home might have a vested interest in reducing Cannes solely to a phase in the publicity-and-awards-awareness rollout. (Not calling anyone out here, but one company’s name might rhyme with “Get Clicks.”) In that case, attacks on the festival’s “relevance” could be tactical moves to set terms and to leverage self-enriching changes under the guise of inevitable market forces. Meanwhile, the published commentary about such industry backbiting has often seemed less a shining example of well-informed journalism and more a reflex of ahistorical feed-the-beast hot-takery. On the flip side—and quite a blind side it can be—there are the unforced errors or procedural inertia on the part of Cannes’ programming culture, which closes off fresh avenues of cinematic exploration and seems unwilling to take the leaps of faith routinely granted to brand-name auteurs and homegrown journeymen, but not to the underrepresented swaths of the creative population who might just possibly be making great work as well. All of which feels like obligatory preliminaries but necessary ones, lest an important institution years in the making get dismantled and picked over as opposed to rejuvenated and redeployed.

Are ya ready for the movies yet?? Whatever else can be said against its name, the 71st edition of Cannes was still a festival that, for its first full day of films, opened with jaw-dropping artistic ambition: Wang Bing’s eight-hour document of Gobi Desert work-camp survivors from Maoist China, Dead Souls. “Une oeuvre unique,” Thierry Frémaux said after taking the stage (albeit in the annex-like Soixantième theater), undergoing a bear hug by the delighted director. You can read about Wang’s shot across the bow of historical oblivion elsewhere in this issue (see Make It Real). Dead Souls might not have been the hot ticket that early day, as was the case with Directors’ Fortnight opener Birds of Passage (which features a drug-dealing Peace Corps American asking the main characters to “Say no to Communism”), but Ciro Guerra and Cristina Gallego’s predictable crime-family Epic-with-a-capital-E, touted as a Godfather inheritor, looked like a transparent watch-me-now bid for even bigger budgets, with screenplay groaners aplenty.

Ayka

Better to start at the end, or rather near the end, since the closing-night film was Terry Gilliam’s Long Awaited The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. Sorry, maybe those first two words aren’t in the title, but while the movie was not a disaster and Adam Driver powers through as a jerk director rediscovering the magic of life and cinema and love and stuff, the best thing about this glorified knight’s tale is that it’s done and we don’t have to hear about it again. When it comes to director-protagonists and personal sagas, I’ll take Jafar Panahi’s latest magic trick, 3 Faces, any day, but more on that later. Back to the end: the day before closing night, Sergei Dvortsevoy’s Ayka premiered, giving festivalgoers one final grueling journey. Fresh-faced Samal Yeslyamova won Best Actress for her dauntless portrayal of the title character, a young immigrant worker in Moscow who, in the first few minutes, gives birth to a child, leaves the ward sans baby in a panicked rush through a window like she’s escaping a fire, and walks straight back to her job plucking chickens in a filthy room alongside other exhausted women who are then stiffed out of their hard-earned wages. The sheer forward motion of the close-to-body camerawork harkens back to early Dardennes (or golden age vérité), but Dvortsevoy’s filmic space is a sludgy Russian landscape, cluttered, relentless, broke-down, and otherwise physically defined by attitudes of indifference and exploitation. At the same time, the film acquires mythic and heroic proportions through Ayka’s perseverance and the Tulpan director’s fondness for animal metaphor, with the constant cell-phone buzzing (courtesy of Ayka’s loan-shark creditors) a revivified cinematic device for underlining her beset-by-demons shoestring existence and isolation.

Maybe Ayka reminded too many of previously ratified festival fare (or was not seen by people who had already departed). Definitely not the same old song for Cannes was Ali Abbasi’s Border, adapted from a story by Let the Right One In writer John Ajvide Lindqvist. This Un Certain Regard selection (and section award-winner) centers on the mystery of identity as it follows a customs inspector who happens to be non-human—a fact that is not apparent right away though her difference emerges in her pronounced facial features, the ability to sniff out contraband and bad mojo, the ability to commune with deer, that sort of thing. Absolutely essential to its story of self-discovery is Eva Melander’s outstanding, minutely sensitive performance as Tina, the troll in question—for such is the Scandinavian mythology tapped by the contemporary-set movie. Melander makes possible the film’s entirely persuasive narrative of sexual discovery (leading to one of festival’s most genuinely eye-popping scenes of revelation), which inspired more than one critic to point out the film’s resonance as queer cinema. It’s a pity that Tina’s story has to do double-duty with a pedophilia thriller plot, but Abbasi obviously was keeping feet firmly on genre ground in his quest to try something fresh. (“The way it works is you need an authority like Cannes to give you an official sign saying, ‘This guy is weird in a good way,’” he told one interviewer.)

Leto

Border doesn’t cannibalize itself with self-deprecating irony, which, at the risk of sounding earnest, tends to undermine many American genre efforts just as corrosively as self-seriousness can. That might explain why an often clumsy film like Leto, Kirill Serebrennikov’s yarn about the next-generation rock ’n’ roll revolution in 1980s Soviet Union, charms with its innocent exuberance. Based upon the lives of singer-songwriters Viktor Tsoi and Mike Naumenko (played by Teo Yoo and Roman Bilyk), the film can feature a pop song about summer on the beach and feel just as light and unconcerned and pleasurable as the song itself. That said, its formal techniques are an undigested mess of 1980s-era music-video flourishes and ham-handed to-camera meta-commentary, though I found it remarkably easy to edit those out on the fly (neat trick, that). Perhaps most disturbing is what shadowed this and other Russian offerings—how Soviet suppression, so useful as an artistic foil across decades of cinema, has returned under new, bottomlessly cynical management. Put a different way: Tsoi and Naumenko must stage their concerts at an adorable state-sanctioned “rock club” but under pain of censorship; today, Serebrennikov, an outspoken theater director, remains in prison on what are regarded as trumped-up charges.

Serebrennikov was joined in absence by Panahi, still detained within the confines of Iran despite official overtures from the festival. That didn’t prevent the director from making a road movie/mystery tour/Kiarostami tribute, 3 Faces, which (barring the existence of some world-building CGI console in his house) evidently required him to join co-star Behnaz Jafari on treks into rural areas of the country. They play themselves or versions of themselves, and once again, the biggest joy for me is the notion of Panahi as famous director getting recognized in the street, though in this case it is more Jafari who plays the object of fascination to starstruck villagers (except those who “don’t want entertainers here”). Like a refraction of Taste of Cherry’s premise, the object of their car trip is to find a young distraught woman who sent Jafari a cell-phone suicide video. 3 Faces shows Panahi to be ever the resourceful formal escape artist, as he avoids boxing himself in, weaves in some hilarious and scarily blunt encounters with heartland conservatism, and elegantly, movingly reunifies his by-now reflexively reflexive structure with a (not disposably) wistful sense of destiny in the world.

Panahi and Jafari’s buddy act was one of a few makeshift families at this year’s Cannes, in strange synchrony with Elif Batuman’s fascinating recent New Yorker essay about Japan’s thriving business in fictive family members for hire. None features them more prominently than Palme d’Or winner Shoplifters, already a record-breaking success for director Hirokazu Kore-eda back home. Like Panahi, Kore-eda breathed new life into his preoccupations with this story of a family headed by a factory worker; her grifter husband, introduced schooling his son in the five-finger discount; and the grandmotherly matriarch of the bunch. The twisty drama is at once traditional in its neorealist narrative of survival under adversity as a necessary process of self-fashioning, and utterly modern in the way Kore-eda pulls no punches about the upshot of their charade. Sometimes reality demands fantasy—and you might say the same about Cannes.

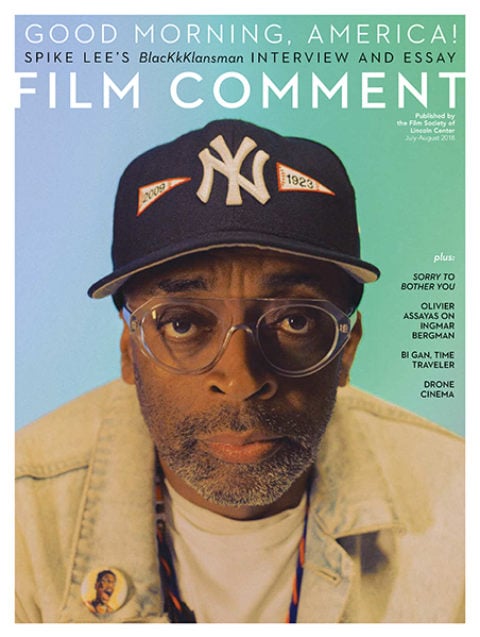

Nicolas Rapold is the editor-in-chief of Film Comment.