Festivals: Why Settle for Less?

There was a moment in each of three very different films at the 71st Cannes Film Festival that made me come alive. Form and meaning fused, and suddenly movies were not beside the point. These epiphanies occurred, respectively, in the final seconds (just before the end credits) of Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Livre d’image (The Image Book); at the opening of the coda to Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman; and midway through Lee Chang-dong’s Burning. What more could one want of any film or any film festival—even one as grueling as Cannes—than such epiphanies? Of course, the films in which they occur have to be good enough to allow one to experience not just a shock or a thrill, but rather an aesthetic, philosophical, and political revelation—all of these at once.

As always, it’s a privilege to be at Cannes, especially if you have a good pass (in the upper half of the spectrum of colors), which is an assurance that you won’t get locked out of screenings, provided that you queue at least 45 minutes in advance for “hot” films. (What often accounts for a film’s cachet is that at least half the audience hopes that this will be the one to end a career. You know who you are, Lars von Trier.) The festival was noticeably less crowded this year: fewer participants, fewer people hungrily star-gazing on the Croisette. In part, this was due to the new schedule—a week earlier than in past years, which meant that the summer sun hadn’t quite arrived on the Côte d’Azur, and also that there was no overlap with the neighboring Monaco Grand Prix, and therefore fewer hordes of guys in knock-off racing gear and no Lamborghinis cruising the back streets. One has to wonder why people who are not cinema devotees or in the movie business would want to cross lines of machine-gun-toting police along the Croisette, or put one’s bag and oneself through the near equivalent of airport inspection (no, you don’t have to take off your shoes, although jury member Kristen Stewart walked barefoot up the red carpet in the rain), just to get into a theater. My colleagues and I were glad to have the security, and the festival guards were exceptionally polite (they hadn’t been so in previous years), but still, most of the films serve as enough of a reminder about the dire state of the world without having to run a gauntlet to get to your seat.

It was the 50th anniversary of May ’68, and Cannes responded, if a bit obliquely. The festival poster was an image from the original PR campaign for Godard’s Pierrot le fou, which it should be noted was released in 1965, and, although a great film, was nothing like the cinema that Godard was already envisioning when he and his fellow New Wave filmmakers closed down the festival in 1968. But post-’68 Godard was present in all his radicalism—and in competition, where Le Livre d’image won a special Palme d’Or (the first of its kind) for the director’s “continually striving to define and redefine what cinema can be,” as jury president Cate Blanchett succinctly explained at the awards ceremony. A few purists were dismayed that Godard hadn’t won the “real” Palme, which went to Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Shoplifters, but in fact, the necessity of inventing a new award speaks to the fact that Godard, although blatantly influential, has for 60 years continued to develop a language of images and sound that is always ahead of the game.

The paradox is that beginning with his magnum opus Histoire(s) du cinéma (1989-99), Godard has raided the image bank of cinema, painting, and photography in order to simultaneously show us our history and also our possible future, conditioned by evolving technology. Histoire(s) was of and for home video; Goodbye to Language (2015) made eyes spin in their sockets with its use of 3-D. And now, Le Livre d’image is a work for a single-channel projected moving image coupled with quad sound. Not only were image and sound in dialogue but also the speakers (audio tracks) were synced with one another. In the two screenings in Cannes’ huge Théâtre Lumière, the speakers were perfectly placed and balanced, which is the only way the movie can be properly experienced. (Kino Lorber, the film’s U.S. distributor, is going to have its hands full trying to make that happen.) Of all the feature-length movies Godard has made since Histoire(s), this is the most abstract, in the sense that only the last of its five sections has anything like a narrative. Godard has used almost all of these images in other collage films, but here they are even more fragmented, transformed with variable speeds, colorization, and other digital processes. “Brecht said, in reality, only a fragment carries the mark of authenticity,” says Godard, whose voiceover narration—like a broken epic poem—is the dominant audio element.

BlacKkKlansman

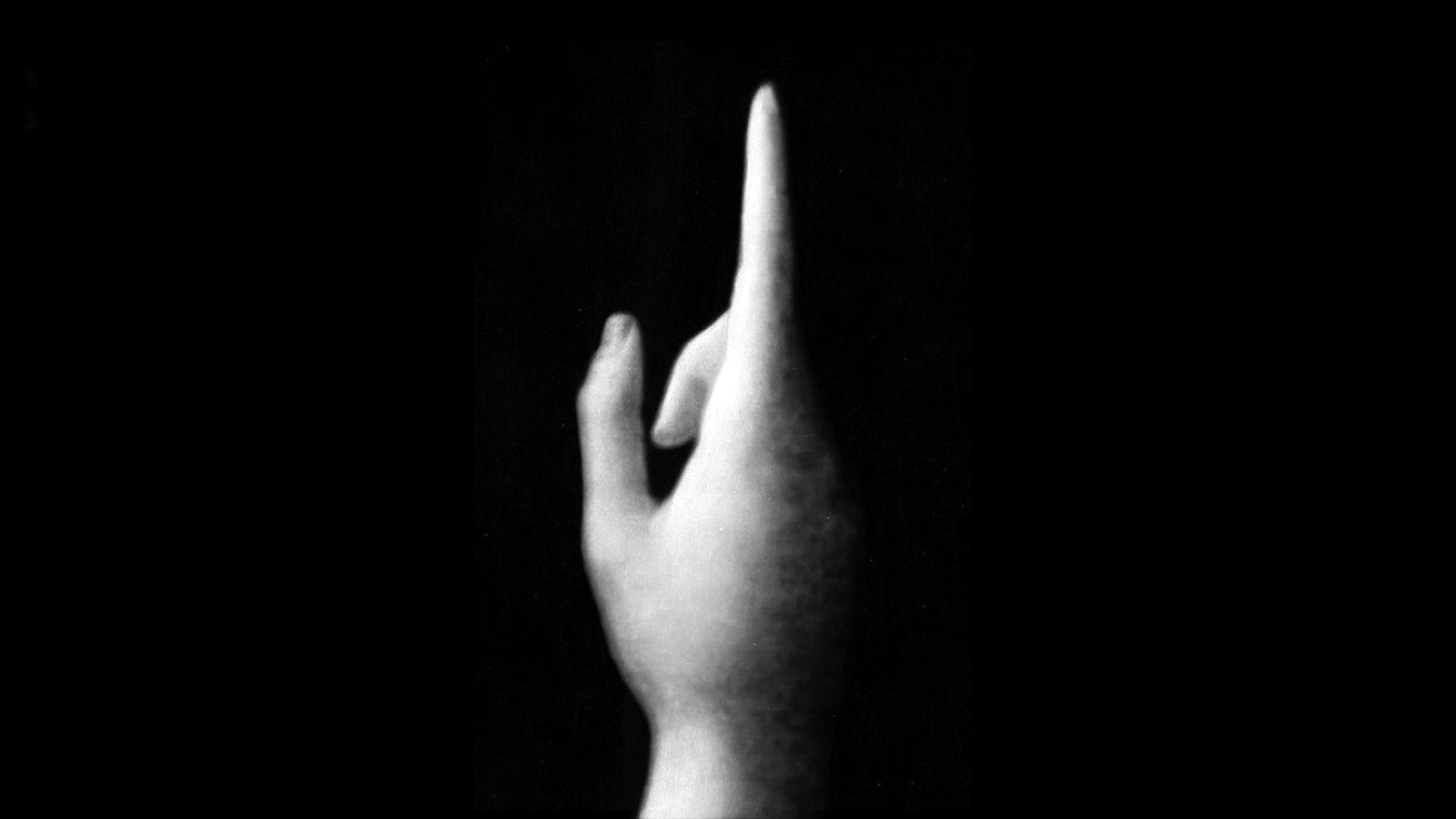

Basically Le Livre d’image is about history as nightmare and the looming end of the world as the end of the nightmare, all of which we must face with hope: “…And even if nothing would be as we had hoped / It would change nothing of our hopes / They would remain a necessary utopia…” The film begins with something that looks like a black-and-white reproduction of a detail from Leonardo’s final painting, St. John the Baptist—a hand with the index finger pointing upward. In Renaissance art, that pose of the hand is a sign of the hope of heaven. And just before the end of the film, all the speakers come into sync for the last words of Godard’s raspingly voiced text: “ardent espoir” (“ardent hope”). I don’t think I imagined any of this, including my own experience of epiphany, but I won’t know for certain until I see the film again, because as everyone will tell you, it is very dense.

Similar in one respect to Le Livre d’image, Lee’s BlacKkKlansman is concerned with how movies make us believe and identify. Opening with clips from two American film classics, Gone with the Wind and The Birth of a Nation—the first romanticized slavery, the second reignited the KKK—the body of the film tells the incredible but true story of Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) who was the first black cop on the Colorado Springs police force and in 1979 went undercover to infiltrate the KKK, with the help of a white Jewish cop, Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver). Because Ron sees himself as a blaxploitation detective, the film sometimes follows his imaginative perspective, but it also interjects scenes between Ron and Flip that are quietly naturalistic, and others that push beyond blaxploitation into the exploding genre of African-American surrealism that in this century goes back to Lee’s Bamboozled (2000) and has come to full bloom in the TV series Atlanta, Jordan Peele’s Get Out, and Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You. BlacKkKlansman’s stylistic shape-shifting is simultaneously unsettling and entertaining. Is it a satire and, if so, is it okay that we’re laughing at those ridiculous men in their white sheets, um, lynching people, and at the banal evil of David Duke (Topher Grace) because after all, it happened 40 years ago? And then, after what Lee’s editing smarts lead us to believe is a pretty devastating final sequence, he takes it a step further by cutting to news footage of the white supremacist riot in Charlottesville, ending with the homicide of Heather Heyer. We’ve seen the footage dozens of times on TV and online, the truth ground out of it through repetition, but projected on the giant screen of the Lumière, every digitally polished pixel proclaims what Lee promises in BlacKkKlansman’s opening titles: it is incontrovertibly “fo’ real sh*t.” And what, and by what means, are you doing something about it?

The mesmerizing and mysteriously beautiful scene that occurs in the middle of Lee Chang-dong’s Burning seems to come out of nowhere. It is a widescreen shot of a young woman, Haemi (Jun Jong-seo), dancing, her back to the camera and to the two male rivals for her attention. For one, Jongsu (Yoo Ah-in), she is an impossible object of desire; for the other, Ben (Steven Yeun), an inconsequential fuck toy, soon to be discarded, or worse. At this moment, as she takes off her shirt and begins to dance, she is oblivious of both of them. Enveloped in the light of the setting sun she takes possession of a vast space that is simultaneously the screen itself and the empty landscape before her eyes, which might border the DMZ with North Korea. The shot continues for I’m not sure how long, but I wished it had been forever. Soon after, she disappears from the narrative, which turns into a male, closeted homoerotic psycho-drama—a very good example of one, but a genre of which I’ve already had more than enough to fill a lifetime.

Happy as Lazzaro

Under pressure to show more films directed by women, the Competition managed to come up with a mere three. Of them, Eva Husson’s puerile Girls of the Sun is not just bad, it’s infuriating; if any people deserve a great film made about them, it’s the Kurdish women freedom fighters. And I suspect that Nadine Labaki’s Capharnaüm, which was acquired by Sony Pictures Classics, will be reedited to make its radical feminist premise more clear—that the conservative values that make motherhood the only acceptable role for women are devastating both to parents and to the children they cannot afford even to feed. Hopefully Labaki will do away with the heavy-handed music and allow the extraordinary performance by Zain Al Rafeea, as a 12-year-old runaway who sues his parents for bringing him into the world, to compel hearts and minds. You want only the best for this boy, while knowing that you probably are seeing a suicide bomber in the making. Finally, Alice Rohrwacher follows her beguiling The Wonders (2014) with the no less lyrical and even more fabulist Happy as Lazzaro, which, if you read between and beneath the exquisite images, is a condemnation of Italy’s upper class and the supposedly benevolent Italian state for exploiting the most vulnerable and pitting the have-littles against the have-nothings. Rohrwacher owes a lot to Pasolini’s political fables, but by the end of Happy as Lazzaro, the strain of finding beauty in horror takes its toll.

If films by women left something to be desired, several by male directors who put women at the center were more rewarding. The jury’s disregard notwithstanding, the best performance by an actress was Zhao Tao in Jia Zhangke’s Ash Is Purest White. The film is a restless journey through the political and social mainstreaming of China in the first two decades of the 21st century, and in counterpoint, the development of a gangster’s moll into an independent woman capable of resisting the patriarchal values of state and family. In 3 Faces, his best film in many years, Jafar Panahi shakes off house arrest and, with actress and friend Behnaz Jafari, drives into rural Iran to find out if a young woman who was not allowed to attend acting school really committed suicide.

At the awards ceremony, the #MeToo presence, which had been building throughout the festival, was succinctly given voice by Asia Argento, who took to the stage to say that she had been raped at Cannes by Harvey Weinstein, for whom the festival was a hunting ground. Looking out at the rows of tuxedo-clad power brokers, she went on to say that we know there are others and we are coming for you. Argento later tweeted that the only person who immediately thanked her was Spike Lee.

Amy Taubin is a contributing editor to Film Comment and Artforum.