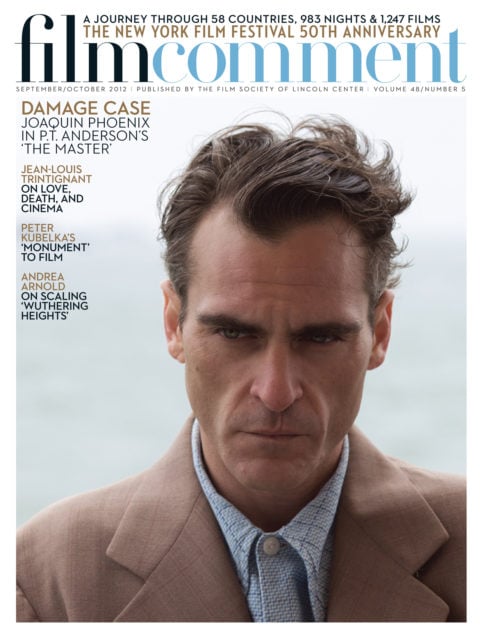

Executive Action

Do we expect too much of our leaders or too little? Consider this Hollywood scenario: a genial party hack is elected U.S. president, “dies” in a car wreck, and is subsequently reborn as a messianic leader who, possessed by some higher power, establishes martial law, ends unemployment, liquidates organized crime, and browbeats the world into accepting a Pax Americana.

Materializing in the spring of 1933, based on a novel by British politician Thomas F. Tweed that was anonymously published in the U.S. the same month that Hitler came to power in Germany, Gabriel Over the White House was a movie with something to say—indeed, it was a memo for America’s incoming president Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent (via producer Walter Wanger and director Gregory La Cava) by media baron William Randolph Hearst.

An early film enthusiast, Hearst was making elaborate home movies and producing newsreels as early as 1911; he introduced America to Pathé’s sensational Perils of Pauline in 1914 and, a year later, was manufacturing his own serial adventures, which, no less than Hearst newsreels, were readily drafted into his political crusades. The 1917 Irene Castle vehicle Patria agitated so vehemently for wars against Japan and Mexico that President Woodrow Wilson attempted to have it suppressed. Thereafter, Hearst calmed down. After 1919, his Cosmopolitan Pictures were mainly devoted to showcasing the talents of his mistress Marion Davies.

In 1924, two years after a final bid for public office, Hearst and Cosmopolitan relocated from New York to California, entering into a mutually beneficial alliance with Louis B. Mayer’s newly created MGM. Hearst promoted Mayer and his studio; MGM underwrote and distributed Cosmopolitan’s releases. Still, however immersed in the dream worlds of Hollywood and San Simeon, Hearst remained politically powerful. The onetime scourge of monopoly capitalism had fallen hard for laissez-faire President Calvin Coolidge and his Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, whom Hearst would support over Herbert Hoover for the Republican presidential nomination in 1928.

Hearst turned on the Republicans after the stock market crash, while holding Hoover personally responsible for the failure of European powers to pay back their war debts. As the Depression deepened, the press lord rejoined the Democrats even while expressing his admiration for Mussolini; initially backing Speaker of the House John Garner for president, Hearst would switch candidates on the fourth ballot of a deadlocked Democratic convention to insure (and take credit for) Roosevelt’s nomination.

Gabriel Over the White House (Gregory La Cava, 1933)

Detailing a benign dictatorship founded on the clever exploitation of film (and television!) propaganda, the novel Gabriel Over the White House might have been written for Hearst. In addition to dispensing with Congress, federalizing the police, and embarking on a massive public works project, President Jud Hammond leads Europe in a successful war against Japan, disarms the world, collects war debts, abolishes tariffs, and, having restored prosperity while establishing peace on earth, passes away—mission accomplished.

Even before the novel’s American publication, ambitious young producer Walter Wanger had secured the rights and, bypassing MGM’s devotedly Republican studio boss, took the project directly to Hearst, who introduced a few more of his pet ideas into the scenario and rewrote much of the dialogue. All but screaming “Extra! Extra!” the movie was directed in 18 days for a frugal $180,000 by La Cava, himself a former newsman, having managed the Hearst editorial cartoon department for three years in the early Twenties. (It is surely La Cava’s reputation as a director of screwball comedy that prompted Georges Sadoul, among other European film critics, to read Gabriel as satire; the director himself compared the movie, in its potential impact, to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.)

Walter Huston, “re-elected to screen presidency” per one Hearst scribe, after playing the title role in D.W. Griffith’s 1930 Abraham Lincoln, was an appropriate icon for a movie that evokes the Great Emancipator at every opportunity. Karen Morley, cast as a professional femme fatale in Wanger’s last topical melodrama, The Washington Masquerade, appeared as President Hammond’s mistress turned acolyte Pendie Molloy, with Franchot Tone making his movie debut as Hammond’s loyal aide-de-camp Beek.

Initially, Hammond is a bushwa-spouting glad-hander. Confronted by the economic crisis in the form of a disheveled reporter (Mischa Auer, Hollywood’s go-to Bolshevik) who gives an overwrought account of the current situation, Hammond takes the Hoover position that unemployment and gangsterism are local issues, proving himself a master of platitude when he calls on the American people to weather the crisis with “the Spirit of Valley Forge.” Compared to the martyred John Bronson (David Landau), leader of the Army of the Unemployed that, like the Bonus Marchers dispersed by Hoover during the summer of 1932, has massed on Washington to demand jobs, Hammond is devoid of moral authority. Then he cracks up his car on a 100 mph joyride.

The movie advances no vice president, but as Hammond lies in a coma, an invisible presence enters through the White House window—celestial harps and patriotic fanfares accompany the billowing of the curtains—to occupy the presidential body. (Not Abraham Lincoln, Zombie Hunter but Abraham Lincoln, Zombie!) First on the divine agenda, after putting Pendie in her place (and, effectively, passing her on to Beek), Hammond addresses the Army of the Unemployed, still camped outside his bedroom even after their leader has been slain by gangsters. In a curious speech chastising the “stupid, lazy people of the United States,” the president promises to stimulate economic recovery by creating an Army of Construction. In chilling long shot, the crowd begins to sing: “My eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord…”

In his sense of mission, belief in direct action, militant asceticism, isolation from family and friends, and embodiment of the simple, honest virtues sentimentally associated with the common man, the new Hammond is represented in terms remarkably similar to those with which contemporary Germans were encouraged to see their Führer (who, as if mimicking Hammond, would declare that he followed his path “with the confidence of a somnambulist”). America’s new dictator fires his cronypacked cabinet, cows Congress, and establishes a Federal Police force that engages the gangsters in a futuristic tank war, with due process suspended in favor of summary judgment. (This extra-constitutional war against crime echoes the means used by Huston as New York’s police chief a year earlier in Cosmopolitan’s Beast of the City.)

Domestic chores accomplished, Hammond can now address Hearst’s pet peeve, the collection of European war debts. Gathering diplomats from all the major powers (save the unrecognized Soviet Union), he treats them to a display of American military might and, warning that “the next war will depopulate the earth” with aerial bombing, death rays, poison gas, and “inconceivably powerful explosives,” offers a disarmament treaty that will allow them to divert defense spending to the payment of their obligations. Hardened diplomats dab their eyes; the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” is reprised. Treaty of Washington signed, Gabriel departs Hammond’s body and the film ends with the White House flag being lowered for “one of the greatest men who ever lived.”

Gabriel Over the White House (Gregory La Cava, 1933)

Promoted as “The Rebirth of a Nation,” Gabriel opened wide on April 1, 1933, well into the drama of Roosevelt’s first 100 days. Hearst papers, some serializing the novel, were uniformly ecstatic. “At last someone has realized that motion pictures, the greatest expression in world history, may be used for some purpose other than the mouthings of dimpled ingénues and the posturing of hycinthean youths,” Regina Crew enthused in the New York American.

The non-Hearst press was more apt to see the movie as “hysterical propaganda” (New York Post) or even “hysterical Hearst propaganda” (New York World-Telegram). New Masses and the Daily Worker were not the only publications to characterize Gabriel as “fascist.” Hearst’s enthusiasm for Mussolini had scarcely abated; on March 5, the day after Roosevelt’s inauguration, the American’s opinion page featured articles by Il Duce and his apologist, Futurist theoretician Filippo Marinetti, arguing for the very positions advanced in Gabriel’s final reel. The same edition also ran an unsigned, full-page editorial titled “Much Talk—No Plan” which began “The voice of the people is the voice of God” and concluded with extensive quotations from the “soon to be shown” Gabriel Over the White House.

Hearst, however, had been confounded; his plan to open Gabriel on the first day of Roosevelt’s presidency was thwarted by a freaked-out Mayer who, reportedly apoplectic after attending the movie’s Glenwood preview, had shipped a print to the studio front-office back East. “Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer is gravely concerned over Gabriel Over the White House,” The New York Times reported on March 17. Given current “economic and political conditions,” certain unnamed industry honchos deemed it “unwise to show a film which might be regarded by the nation at large as subversive and by foreign countries as invidious.” After screening Gabriel in New York, both MPAA Code enforcer Will Hayes and MGM chairman Nicholas Schenck “immediately declared the picture should never be shown,” at least in its current form. Ads were pulled and Gabriel “was rushed back to Hollywood” for reshoots.

In fact, it would be more accurate to say that Gabriel was returned to the shop to prepare alternate versions—one of which exists as a unique print in the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. Introducing a screening at the Bologna Film Festival last June, archivist Nicola Mazzanti referred to his find as Gabriel’s “European version,” although to judge from the absence of subtitles and the reworking of the movie’s longest, most didactic sequence (a 10- minute dramatized Hearst editorial), it seems most likely that this Gabriel had been actually reedited for the U.K.

In Gabriel’s saber-rattling U.S. release, Hammond gathers delegates from the unnamed League of Nations on the deck of an American destroyer and, in a speech broadcast live to the world, declares them “morally bankrupt” for failing to honor their solemn obligation to the United States. A sort of staged Pearl Harbor, in which the U.S. bombs two of its own obsolete ships, serves to bully the assembled top hats into signing the “Washington Covenant.”

In the European version, as Mazzanti pointed out, the sequence has been redubbed and reedited to eliminate Hammond’s increasingly bellicose insistence that “the debt must be paid.” Rather than cow foreign diplomats with Old Testament rhetoric and a fearsome show of force, he destroys an American battleship as a good-faith gesture, leading the way towards disarmament under the auspices of a new international entity, the “Union of English-speaking Nations for Peace and Progress.”

Scarcely less significant is what the European Gabriel leaves in. Here, too, Hammond collapses upon signing the Washington Covenant but then, as in Tweed’s novel, reverts to his old corrupt self. Waking from weeks of “crazy” dreams, the president realizes that, since the accident, “a mad dog has been loose in the United States”—namely himself. Hammond gets so worked up in declaring his intention to renounce the Washington Covenant that he suffers a minor spell. Pendie, whom he is again addressing with his old familiarity, is also stricken—with horror.

Deliberately withholding Hammond’s medicine, a tearful Pendie allows him to die a hero in her arms. The elimination of this scene spared Americans the emotional complexity of her moral sacrifice— a fallen woman redeemed, or perhaps damned, by murdering the man she loves, who also happens to be President of the United States, for the sake of his dictatorial legacy.*

Writing in the New Masses, Marxist critic Harry Potamkin saw Tweed’s novel as prophetic: “The Hammond buildup resembles the Roosevelt. Television [sic] spreads Jud Hammond in the homes and hearts of America; recall Roosevelt’s radio tête-àtête with the American citizens on the bank holiday. [Hammond’s press agent], like W.R. Hearst, is a California newspaper publisher and son of a newspaper publisher, and also a film producer. Like Hearst he produces a film in support of the President.” That movie—a meretricious glorification of the martyred Bronson, secretly funded by Hammond— was, in essence, the movie Hearst hoped to make.

The man for whom Hearst’s message was intended was far from displeased; Gabriel was reportedly screened several times at Roosevelt’s behest. A media-savvy master of public relations, the president doubtless realized that Hearst’s perverse envisioning of the New Deal could only help condition the public to expect dramatic action from Washington and that, no matter how extraordinary, his actions would seem normal compared to Hammond’s mad-dog behavior. Hearst, however, would not be pleased with Roosevelt, whom he believed to be unduly influenced by “communist advisors.” More impressed by Hitler, the newspaper magnate ran guest editorials by leading Nazis Hermann Göring and Alfred Rosenberg and expressed a desire for a “system of government of the date of the airplane.” One wonders how he appreciated the fascist dynamo that was Triumph of the Will.

Gabriel Over the White House may have been, as Variety put it, “voluptuously patriotic,” but for all its insane hero worship, fevered nationalism, and incantatory ressentiment, it was scarcely the last word in cinematic fascism—or, Pendie’s passion notwithstanding, even an appeal to the collective libido. For that, Hearst would have had to drop “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and, taking a lesson from Warner Bros.’s contemporary “New Deal in Entertainment,” hire Busby Berkeley to choreograph a goose-stepping mass tap-dance of the unemployed.

*Although it is clear from the outset that Hammond and Pendie are lovers, the U.S. print omits the fade-out kiss that, placed at the end of their first scene together, makes the relationship absolutely unambiguous.