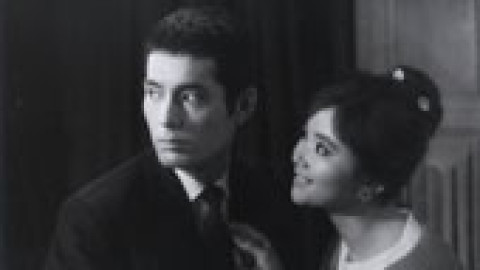

1. Cruel Story of Youth (1960)

An amped-up tear-down of the Fifties “economic miracle,” Oshima’s second feature is as lurid and full-fistedly tabloid as anything by Sam Fuller. A teenaged thug date-rapes his soon-to-be soulmate and soon the pair are running a shakedown scam on horny salarymen. (Available on video from New Yorker.)

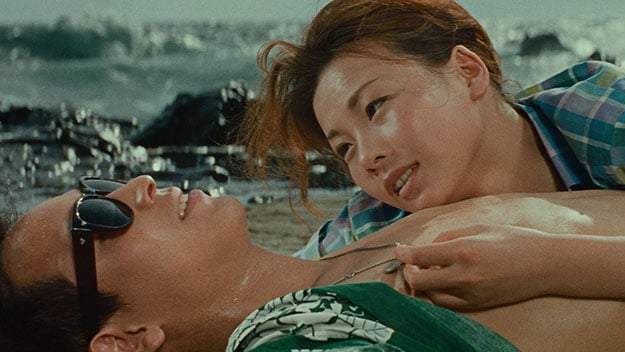

2. The Sun’s Burial (1960)

A viper-like hooker entreats desperate slum dwellers to sell their blood to a ramshackle clinic, then resells the blood to a cosmetics factory. A fresh-faced boy is beaten with a bucket of innards. Rebel Without a Cause written as a fireball of hopeless destruction. This is Oshima spitting on his national banner and partying Roger Cormanöstyle. As critic Tadao Sato once wrote, the film unfurls “like a scroll painting of Hell.” (Available on video from New Yorker.)

3. Violence at Noon (1966)

Also more toothsomely known as Floating Ghost in Broad Daylight, this portrait of rape, re-rape, and the end of a socialist farming collective is as jagged as a hacksaw. (Available on video from Kino.)

4. Death by Hanging (1968)

Based on the true story of a young Korean in Japan who raped and murdered two girls, and was sentenced to death. In Oshima’s version, the hanging fails, the Korean develops amnesia, and a trial ensues to remind him of his guilt, and hang him once again. A comedy about capital punishment the way Godard’s Weekend is a car crash flick about the ideology of trash collectors.

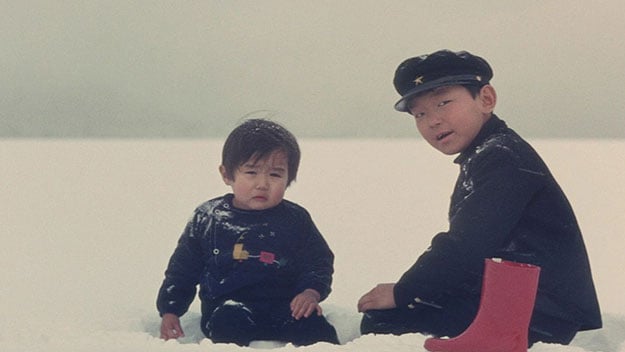

5. Boy (1969)

A war veteran and his wife force their ten-year-old son to dash in front of speeding cars, in order to collect insurance settlements. Another true story, and oddly humanist in affect, for Oshima. The quintessence of the director’s recurrent metaphor: postwar child (= modern Japan) as sacrificial lamb for post-traumatic patriarchy.

6. The Man Who Left His Will on Film (1970)

Film editing as a revolutionary act. Students document the so-called War of Tokyo (a series of street demonstrations marred by police over-reaction). One of the filmmakers may or may not have died during the shoot, and the film found in his camera consists of footage of placid street scenes. In cutting them together, another student is driven to suicide. Uncompromising and extraordinary, though tough going for the uninitiated, this is one of Oshima’s signature accomplishments.

7. Night and Fog in Japan (1960) & 8. The Ceremony (1971)

Two widescreen, candy-colored canvases, both staged as a succession of weddings and funerals, both punctuated by shrieking and nihilistic rage. The first is a Resnais-inflected palimpsest of three generations of college-campus radicals, each haunted by the failures and betrayals of the others. The second dodges the specifics of history, elliptically leapfrogging from one ceremony to the next in the lives of a single family. As gorgeous as a Vincente Minnelli fantasia, as demanding as a Robbe-Grillet rewrite of Beyond Good and Evil, the films’ objective is the expansion of the average filmgoer’s political consciousness. The result is the cracking of their skulls.

9. In the Realm of the Senses (1976)

By global consensus, a masterpiece, though some of us find this celebration of a famous case of sexual devotion as death-driven transcendence mildly interesting, but altogether inessential. The story of geisha Sada Abe and a client whose passion is pornographic and fatal: the director’s recurrent curiosity about strangulation and castration reach a hardcore pitch in this made-in-France and banned-in-Japan art-house snooze. (Available on video and dvd from Fox Lorber.)

10. Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1982)

David Bowie (in his worst performance) gives Ryuichi Sakamoto a kiss and destroys the final vestiges of the samurai mind. Tom Conti is the titular Lawrence, an English POW well-versed in most things Japanese, but it’s the baby-faced Takeshi “Beat” Kitano who speaks the title line and steals the entire show. Met with a degree of critical derision by many, the film has improved with age and cries out for a properly letterboxed DVD edition.