Encore: Demon Lover Diary and Seventeen

Class-topping graduates of Sundance High in their respective years, American Movie (99) and American Teen (08) met with very different fates in the real world—the former grossing more for Sony Pictures Classics than its horror-filmmaker subject Mark Borchardt could ever hope to see from his Coven, the latter making less for the now-defunct Paramount Vantage than its kids’ parents will likely shell out for a year of college. We could blame the Bush years for the economic downturn of quintessentially American youth docs, but there’s more to gain simply by noting that the alarmingly uncertain lives of Midwestern schlockmeisters and high-schoolers were captured much earlier—and better—by a little-known pair of MIT Film Section alums.

In 1975, Joel DeMott and her boyfriend Jeff Kreines road-tripped from Cambridge to suburban Michigan, toting the one-person synch-shooting rig they had designed in school, to capture the farkakt making of the low-budget horror flick The Demon Lover (released in 1977), on which Kreines had been hired as cameraman. DeMott’s proto–American Movie, the hilarious and harrowing Demon Lover Diary, made its debut in 1980, whereupon she and Kreines moved to Muncie, Indiana, and started work on their proto–American Teen—a documentary about the life and times of a cross section of high-school kids. Hilarious and harrowing itself, the resulting film, Seventeen, was slated to air on PBS. Why it didn’t is a long story—25 pages long as typed (single-spaced) by Kreines and DeMott in 1983, and amounting now to one more invaluable document of an earlier doc boom gone bust.

If these pioneering students of Ed Pincus and Ricky Leacock have been shut out of the American documentary canon, it’s for lack of exposure, not acclaim. When Seventeen premiered at New York’s Film Forum only days before The Breakfast Club began dishing it out to the class of ’85, the critics lined up to give out As. In The New York Times, Vincent Canby called Seventeen “one of the best and most scarifying reports on American life to be seen on a theater screen since the Maysles brothers’ Salesman and Gimme Shelter.” Dave Kehr saw an “emotional” counterpoint to Frederick Wiseman’s institutionalism, while Armond White, in these very pages, praised its “moral” riposte to Steven Spielberg’s “sad inanity” (that was then).

Demon Lover Diary

“Unless society changes,” DeMott told White of Seventeen’s working-class Muncie kids, “they’ll still be doing what they were doing when we filmed: floating back and forth between two different worlds—worlds of boys and girls, worlds of black and white.” The segregation of said camps appeared no less stark for the co-directors’ decision to shoot separately—Kreines hanging with the homeboys, and DeMott with the girls. The resulting trust—furthered by the filmmakers’ 18-month stay in Muncie, and by the cameras’ close proximity to the subjects—can be felt at virtually every moment in the two-hour movie, to the benefit of its authenticity and, in turn, the discomfort of authority figures fingered in the 25-page postmortem: the network (PBS), the corporate funder (Xerox), the executive producer (Peter Davis, director of Hearts and Minds), and “the press” (including The Nation and American Film).

Seems like yesterday, as Bob Seger would say, but it was long ago—and what the movie needs far more than notoriety or cultish nostalgia is exhibition. As DeMott told me recently by e-mail: “I care almost feverishly that Seventeen be the movie it is, no longer skinned with its past . . . The fact it was once upon a time covered (or hidden) in shit needn’t be its written fate.”

In that spirit, I’ll offer this: both Seventeen and Demon Lover Diary are positively crucial to documentary film history. That’s in no small part for what these two pioneering films share: a raw, pungent sense that the Seventies killed the Sixties, that law and order would be here to stay (Seventeen’s first words are a home-ec teacher’s orders to “be quiet and sit down”), that the kids who manage to survive will, like the two films, be sent to detention (and won’t go quietly).

Seventeen

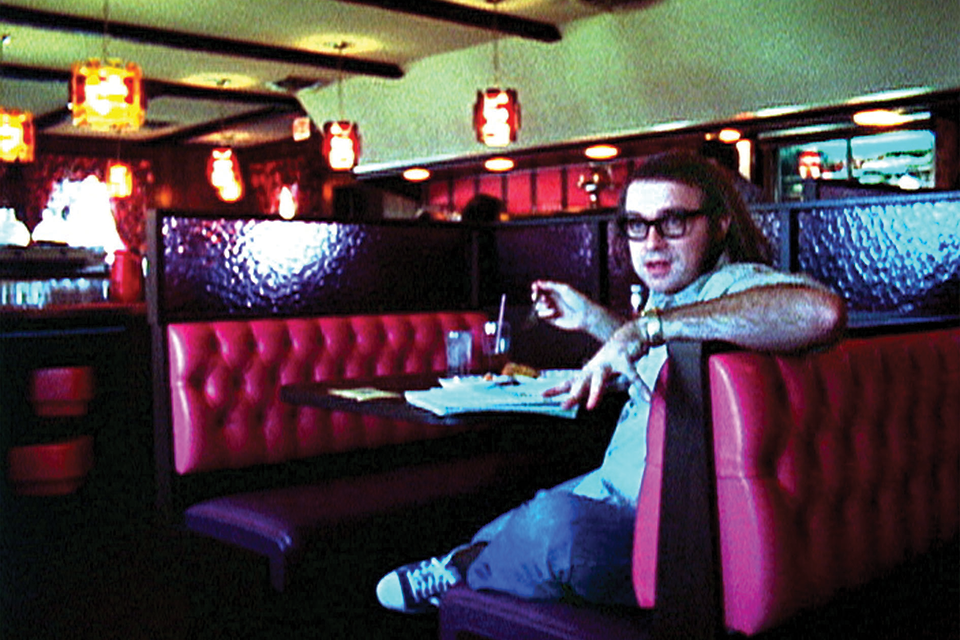

Seventeen is loaded with tap beer, pot smoke, feathered hair, wood paneling, F-bombs, and copious amounts of classic rock, including a radio DJ’s spin of Seger’s ageless “Against the Wind,” requested at kegger’s end by a drunken youth in dedication to a buddy who died just hours earlier in a car crash. Albeit claustrophobic, befitting the subjects’ sideways mobility, Seventeen is somehow funny, in part for how defiantly its editing bucks the old-school rules of vérité in its search for one darkly comic juxtaposition after another. Funnier still, Demon Lover Diary has the hair (much of it facial) and the tunes (“Money” and “Chain of Fools,” to name a well-matched pair), plus DeMott’s sober if snarky voice of reason, whispered playfully into the mic in post-production. Preceding Seventeen by a good half-dozen years, DeMott’s Diary takes the tenets of Direct Cinema more blatantly to task, justly editorializing on the horror production’s utter lack of professionalism, not to mention casting the whole Demon Lover adventure in some doubt from scene one by introducing boyfriend Kreines in full-on slacker mode—shaggy head hardly in the work-for-nothing game.

Is this not DeMott’s distaff diary of how men will be boys? As if Donald G. Jackson and Jerry Younkins’s satanic screenplay isn’t absurdly violent enough, the filmmakers get hard-rockin’ guitar god Ted Nugent—can’t make this shit up, can ya?—to lend his vast arsenal of weapons, which feature prominently in Demon Lover Diary’s suitably cut-rate climax. An odd but hardly incidental scene of prepubescent boys mercilessly mutilating some poor kid’s cardboard fort seems a preview of the destructive American teens (and movies) to come.

And where are they now? Kreines, inventor of the Kinetta Archival Scanner, (used by the Library of Congress for film preservation) lives and works with DeMott in Coosada, Alabama, where they continue to make movies, distribute their golden oldies in 16mm, and prep DVDs for release next year. Jackson—further proving that life, per Seventeen’s sociology teacher, is a combination of hard work and luck—has made several Roller Blade Warriors epics, among a dozen or so other entertainments. And the kids of Seventeen? Older now and still runnin’, most likely, against the wind.