On writing and movies

3:10 to Yuma

To what extent do you think your writing was influenced by movies, even before you began selling stories to Hollywood?

Probably more than I thought. When I started writing, I wanted to make money right away and I chose Westerns because of the market. You could aim for Saturday Evening Post, Colliers, Esquire, Argosy, Adventure, and a number of pulp magazines, like Dime Western, that were still in business. I liked Western movies and they were big in the Fifties.

So when you were writing a story, you were thinking of it, from the outset, as a possible movie?

That was my hope.

Was it just accidental that the stories you were writing, with so much dialogue, almost resembled scripts?

It happened that my style did lend itself—the way I learned to write in scenes, with a lot of dialogue. I think initially I learned as much as I could from Hemingway, and then the style I developed seemed to apply itself to movies: scenes leading to scenes, character development, but always enough action, too.

On the first story he sold to the movies: 3:10 to Yuma

The Tall T

How did that get sold? What was the process whereby you were “discovered”?

The story was in Dime Western, 4500 words; I got ninety dollars for it. The editor insisted I rewrite one of the scenes and do two revisions on my description of the train. He said, “You can do it better. You're not using all your senses. It's not just a walk by the locomotive. What's the train doing? How does it smell? Is there steam?” He made me work for my ninety bucks, which was good. It was in the magazine, and then within a year a producer saw it and bought it.

How about The Tall T (57)?

That was a novella in Argosy, which sold to Hollywood fairly quickly. I found out later that Batjac, John Wayne's company, had bought it originally, and then something happened and he passed it on to Randolph Scott and [producer] Harry Joe Brown. They also added about twenty minutes onto the front end, which I thought gave it an awfully slow opening.

And you had nothing to do with the people in Hollywood who made the movie?

No. I saw that one in a screening room with Detroit newspaper critics. I remember the film coming to the part where Randolph Scott has Maureen O'Sullivan lure Skip Homeier into the cave. Randolph Scott comes in and faces Skip Homeier, who has a sawed-off shot-gun in his hand. One of the critics said, “Here comes the obligatory fistfight.” But Randolph Scott grabs the shotgun, sticks it under Skip Homeier's chin, pulls the trigger, and the screen goes red. They didn't say anything after that.

You might say that was a “defining Elmore Leonard moment.” You have become known for surprising, brutal violence in your stories. How did you come by that penchant?

I wasn't writing for Range Romance, I was writing action stories, six-guns going off, violence a natural part of it, the reason for reading a Western. But never, in 30 short stories and eight novels, did I stage a fast-draw shootout in the street, the way practically every Western movie ends. Later I developed ways of having the violence happen more unexpectedly and low-key. “And he shot him.”

Case Study: The Moonshine War

The Moonshine War

When is the first time you actually went to Hollywood to work on a screenplay?

In '68 or '69, with The Moonshine War. […] I'd go out to Hollywood, stay all week, and go home weekends. I spent at least three weeks out there before Ransohoff fired me from the picture. He said, “You're too close to the forest to see the trees.”

Was he right?

No, not then. Now, when I think of adapting my own stuff, I think there's truth in that. Definitely. But it's not so much that you're too close to it. It's just that all of your enthusiasm went into the original, so how do you get it back up to write the screenplay? To me, if the writing process isn't enormously satisfying, it isn't worth doing. I love writing books. I wrote movies for money.

What did you do for those three weeks?

Met with [director] Dick Quine. I'd go to his house every day and we would sit around and talk about what we were going to do; and then Chris Mankiewicz would come over—he was the liaison between Ransohoff and us—and talk in broad, general terms, never specific, about what should be in the picture. I thought we just wasted an awful lot of time, until finally I wrote the script and then I was fired.

They had another writer for maybe a week and then I was hired back on. Quine liked me and got me back. Ransohoff also had a phonetically written script done by a professor at the University of Kentucky, I think, indicating what the dialogue would sound like with that kind of a rural Southern accent. I kept thinking, Why in the hell don’t they just get good actors who can fake it, or actors born in the South?

Then they ended up shooting the picture in California, not far from Stockton, in the only clump of trees in a rather barren landscape of dun-colored hills. The picture was also miscast. Let’s face it, Dick Quine was not the guy to direct a picture about people who live in “hollers” and talk funny. He had done mainly comedies that were hip at that time: How to Murder Your Wife, Paris When It Sizzles. The Moonshine War didn’t stand a chance.

Did anybody ask your advice about casting?

They always ask, but they don't pay any attention to the writer. Richard Widmark I thought was all wrong for the part of the [bootlegger]—I had pictured someone like Burl Ives with a little 16-year-old girl sitting on his knee. I did visit the set for a couple of days. After a number of takes of one scene, Patrick McGoohan came off the set, walked up to me, and said, “What's it like to stand there and hear your lines all fucked up·?”

Do you feel that what went wrong there was not the script, but everything else—the casting, the locations, the director… ?

There were things about the story I had been obliged to change. In all of my screenplays, I've always gone against my better judgment in listening to the director or the producer, doing what they want so I can get the money and go home and write a book. Or thinking, Well, they know what they're doing—even though something is telling me, Nah, that's not gonna work.

On working with Clint Eastwood and John Sturges on Joe Kidd (72)

Joe Kidd

How much did Clint have to do with the script?

Eastwood and Sturges would come into my office at the end of the day and read the scenes I had written. Eastwood is the easiest guy in the world to get along with. I don't recall him changing that much. He would just agree and pass the pages on to Sturges. The only time I can recall him saying anything was for the scene where Joe Kidd is confronted by an armed faction, near the end of the second act. Eastwood said, “Shouldn't I have my gun out when I say that?” I said, “No, I don't think you need to have your gun out.” Eastwood said, “But my character has not been presented as a gunfighter.” He turned to Sturges, “Don't you think I need my gun out?” Sturges said, “No, you don't need your gun out.” Eastwood said, “Why not?” Sturges said, “Because the audience knows who you are—they've seen all your pictures.” But when the picture was made, Eastwood did have his gun out.

Resurgence: Get Shorty and Jackie Brown

Get Shorty

Was Get Shorty (95) a totally positive experience?

All the way. I must admit I was surprised to see the film had become a comedy. I told [director] Barry Sonnenfeld after I saw it, “I don't write comedy.” He said, “No, but it's a funny book.” Barry and [screenwriter] Scott Frank were conscientious about sticking to the plot and using as much of the dialogue as they could. The lines were delivered the way they were written, seriously, the way I'd heard the characters when I was writing their lines. Gene Hackman was delivering his lines one day in rehearsal, and Barry said, “Gene, that was really funny,” and Hackman said, “Well, I wasn't trying to be.” Barry said, “That's the whole idea.”

I do think my books were getting a little funnier as I loosened up, toward the mid-Seventies. I had become a little freer and easier in the way I was writing—not trying so hard to write—and funny things began to happen to the characters.

Going back to The Big Bounce in '68, however, I've been working pretty much with the same characters: ordinary people who seem a bit quirky, non-heroes, spending as much time with the bad guys—who usually aren't too bright—as I do with the more sympathetic characters. I have an affection for all of them, so I treat them as human beings with much the same desires and hangups we all have. Plot is secondary, not that important to me. Once I know my characters I’m confident a plot will come out of them. I make it up as I go along, not knowing what’s going to happen, never knowing how the book will end.

“Not knowing what is going to happen” is part of the comedy, it seems to me. Part of the Elmore Leonard experience. There are always amazing plot twists in your stories.

What's amazing to me, when I think about it, is that while Hollywood in general prefers plot driven stories—they ask, “What's it about?”—33 of my 35 books, all character-driven and talky, have either been optioned or bought outright for film. I write a book not knowing what's going to happen, so I won't be bored, so I can entertain myself making it up as I go along, establishing characters in the first act I hope to be able to use later on, for a set-piece or two if not turns in the plot. If a plot twist is amazing, as you suggest, it must be at the same time believable. So I write each scene from a character's point of view, with the character's “sound” providing the rhythm of the prose and the believability of what's taking place in the scene. The reader accepts it because the character is there. It might not be acceptable from my point of view, were I an omniscient author who thinks he knows everything. Their “sound” is much more entertaining than mine, so I try to keep my nose out of it. I don't want the reader ever to be aware of me writing. And if the prose sounds like it was written, I rewrite it.

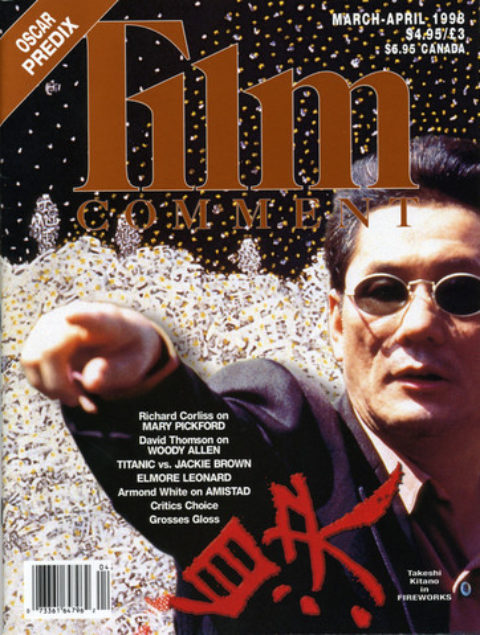

Jackie Brown

On Jackie Brown, did you read Quentin Tarantino's script?

Yeah. It's pretty much the book, with a lot of Tarantino, of course, a lot of additional dialogue.

Did you give Tarantino any input?

I questioned a couple of things, asked why scenes we both liked were left out. But I only spoke to him twice on the phone. The first time was a couple of years ago, when he was just beginning and told me he was going to do Rum Punch instead of Killshot. That was all I heard from him for about a year and a half, until just before he started shooting, in early June ['96], when he called again. He said, “I've been afraid to call you for the last year.” I said, “Why? Because you've changed the title and you're starring a black woman in the lead?” He said, “Yeah.” I said, “Do what you want. You're the filmmaker, you're going to do what you want anyway.”

I was on the set twice, and both times it looked like he was enjoying himself. I met Sam Jackson and Pam Grier, who looked terrific, and I could see why Quentin wanted her. Bridget Fonda I'd met before, doing publicity for Touch, and I was happy to see her in the picture. I trusted Quentin and felt certain the film would work; though I suppose there will be a few smartass critics waiting to take a shot at him.

So, all of a sudden, you're “hot.”

It doesn't seem that long ago I had hopes of being the hot kid, selling my first story in '51 when I was 25. I got on the cover of Newsweek in April 1985, and was seen as an overnight success after little more than thirty years. Now I'm 72 and still at it, writing a sequel to Get Shorty that puts Chili Palmer in the music business, where, with his mob-connected background, he should feel right at home. In doing the research, learning about the record industry, the success of Get Shorty has opened all the doors. We've even had Aerosmith over to the house to drink non-alcoholic beer and play tennis. MGM, Jersey Films, and John Travolta all seem optimistic that it will happen. I am, too, but I have to finish writing the book before we'll know if is any good. Or even what it's about.