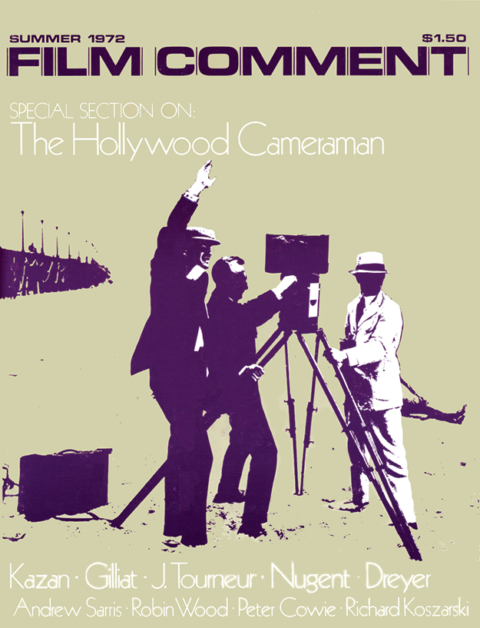

Elia Kazan’s America

The resounding critical and financial failure of The Arrangement in 1969, which elicited the most devastating press Elia Kazan had ever experienced in his quarter of a century of filmmaking, demonstrates how severely estranged he had become from the American film audience. Recently The Visitors, a meager-budgeted, non-union film-the only film Kazan has made since The Arrangement—suggested that despite that crushing disaster, he was attempting to make a totally fresh start. But the brief and pallid run of his latest film, which closed in New York after only eight days and got mostly negative reviews, confirmed once again Kazan’s loss of reputation.

This decline began to become obvious with the release of America America in 1963, but even beforehand, Kazan had lost the patronage of the mass audience he once commanded from the late ’40s through much of the ’50s. (Of the six films released between 1956 and 1969—Baby Doll, A Face in the Crowd, Wild River, Splendor in the Grass, America America, and The Arrangement—only Splendor in the Grass was commercially successful.) One basic reason for this was that he had begun to address himself to a more personal, reflective kind of filmmaking. As Kazan told me, in August 1970:

What I did in films got increasingly personal from about 1952 on. In 1952 I did Viva Zapata! Up until then I had never chosen the subjects or worked on the scripts. I had just accepted jobs. But since 1952 I have always initiated the production. I went to John Steinbeck and said I’d like to make a film of East of Eden; I bought a little book myself and made Wild River; I wrote America America; I wrote The Arrangement. That’s why I gave up the theater—because I didn’t want to continue directing the work of other men.

Kazan’s career is marked by a striking progression from films expressing a detached, liberal social consciousness towards more personal and emotional films. His career reveals a basic tension: an intellectual desire to deal with social issues—as viewed in his less satisfying urban films which utilize a broad and contemporary canvas—versus his instinctual response to the past and to the unworldly inhabitants of cohesive ethnic communities or simple, agrarian environments.

In films like Boomerang! (1947), Gentleman’s Agreement (1947), and Pinky (1949), Kazan was attacking a social problem in abstract terms—political corruption, anti-Semitism, racial prejudice. These early works, which first brought Kazan to the attention of American audiences and established him as a major directorial talent in the late ’40s, were liberal do-gooder films designed to right some evil. In contrast to such sermons and preachings, the films of the mid-’50s and ’60s were intense examinations of characters whom Kazan identified with and recognized as close to himself. In later years Kazan became more deeply involved in the psychological exploration of personal crises. While his work would continue to be marked by a concern for social problems, Kazan’s most interesting films—especially East of Eden (1955) and Wild River (1960), his richest works—combine a careful integration and balance between character development and social issues. These social concerns spring from the inner lives of the central figures themselves, rather than remaining the detached, objectified problems of crime and corruption that the heroes of Kazan’s earlier films succeed in solving.

Frank Overton, Lee Remick, and Montgomery Clift in Wild River (Elia Kazan, 1960)

In a 1947 New York Times’ article, Murray Schumach wrote of Kazan:

He dreams of making epic films that will portray America and its people; movies that will be shot, not in studios, but in fields, mines, factories. Boomerang! was the first short step in that direction. “I want to make folk movies, not folksy movies,” says Kazan. “Odets discovered the Bronx, but no one has discovered America.” Kazan hopes to become the nation’s cinematic Columbus.

Kazan has always had a strong sense of documentary realism in his film work which imbued his early films with an authentic feeling of place. But even his later lyrical evocations of the past—in which Kazan often utilized actual inhabitants of towns like Benoit, Mississippi, Pickett, Arkansas, and Charleston, Tennessee—continued this concern. Wild River’s memorable opening sequence, using actual footage from a grainy, black-and-white newsreel of the ’30s, brilliantly conveyed the urgency of the film’s investigation of rural America, as a semi-articulate farmer caught in the immediate throes of tragedy describes the loss of his family in the raging floods of the Tennessee River. This simple, spontaneous record of anguish persuades us of the authenticity of the film’s environment. The concern with authenticity was attributable in part to Kazan’s training in the “theater of realism“ in the’30s, where he was influenced primarily by the work of Clifford Odets. In 1932 Kazan joined the Group Theater, a repertory company with strong political tendencies. He worked there as an assistant stage manager and later alternated between acting and directing. His theater experience with actors, relying heavily on the Stanislavski method, also enhanced his ability to elicit performances of great believability on the screen. In addition, his early documentary work with Frontier Films in the late ’30s encouraged his interest in discovering the America of the common people.

In his later work, Kazan lived up to his desire to explore America. In moving away from metropolitan settings and into the idiosyncratic regions of America, Kazan brought to the screen fresh visions of sharply-etched worlds whose inhabitants represented the fringes of society, not the bland, conforming, middle-class urban sophisticates depicted in his earlier films. A child immigrant from Turkey, Kazan views America much as we would expect a foreigner to—with a sense of wonder and fascination at the eccentricities of this country. More and more Kazan was drawn to material involving characters from particularized areas of America, notably the South Mississippi (Baby Doll), Arkansas (A Face in the Crowd), Tennessee (Wild River)—but also embracing the small towns of Kansas (Splendor in the Grass), and the northern California communities of Salinas and Monterey (East of Eden). These isolated worlds where change is slow in coming and values remain ultimately stable reveal Kazan’s attraction to innocence and tradition.

The most stirring voice for his celebration of rural Americana and the primitive pioneer spirit is Ella Garth, the 80-year-old protagonist of Wild River. This proud, imposing matriarch, who presides over an eccentric 3,000-acre Tennessee island plantation, repudiates the progress of Roosevelt’s New Deal and the TVA which threaten to uproot her from the only land she and her family have known. In her staunch rebuttal to the building of the dam which will place her entire island home under water, Ella Garth personifies American individualism.

A moving chronicle of the Depression Thirties, Wild River reiterates Kazan’s intellectual interest in American social phenomena which altered the face of the nation. By placing its basic conflict-technological progress versus a more traditional ethic within the intimate, familial canvas of Ella Garth’s dynamic history and personal struggle against the cold, passionless edicts of the New Deal, the film achieves a remarkable depth and power. In one prolonged scene Kazan rests his camera on Mrs. Garth as she recalls her past and the arduous labor of her husband, who founded the virgin island, cleared the trees, and created their rudely-hewn estate. Cane in hand, she roams restlessly through her fields, exciting our imagination with a terse but eloquent narration that catapults us into a more primitive era of America’s past, and calls up the drama and creativity that went into the struggle for survival in untouched lands.

Wild River caught a basic contradiction in American values which the Depression Thirties seemed to accentuate: an irreconcilability between the nation’s belief in rugged individualism and the realities of social progress. This tension gives Wild River its disturbing complexity and ambiguity. The pioneer character has attractive qualities, as Kazan’s moving elegy to this magnificent heroine testifies, but the film finally reminds us that this kind of existence presupposes a rapaciousness, a greed for land in order to preserve one’s individuality.

Several of Kazan’s later films are set in the past, primarily in the Twenties and Thirties, decades of his own youth and early adulthood. This sense of nostalgia and preoccupation with the past suggest Kazan’s attempt to search for his origins through protagonists who set about similar exploration. East of Eden, his most beautiful and penetrating film, seemed to mark Kazan’s first real attempt to examine his past; and as he has admitted, the film’s painfully compelling father-son relationship was deeply personal to him.

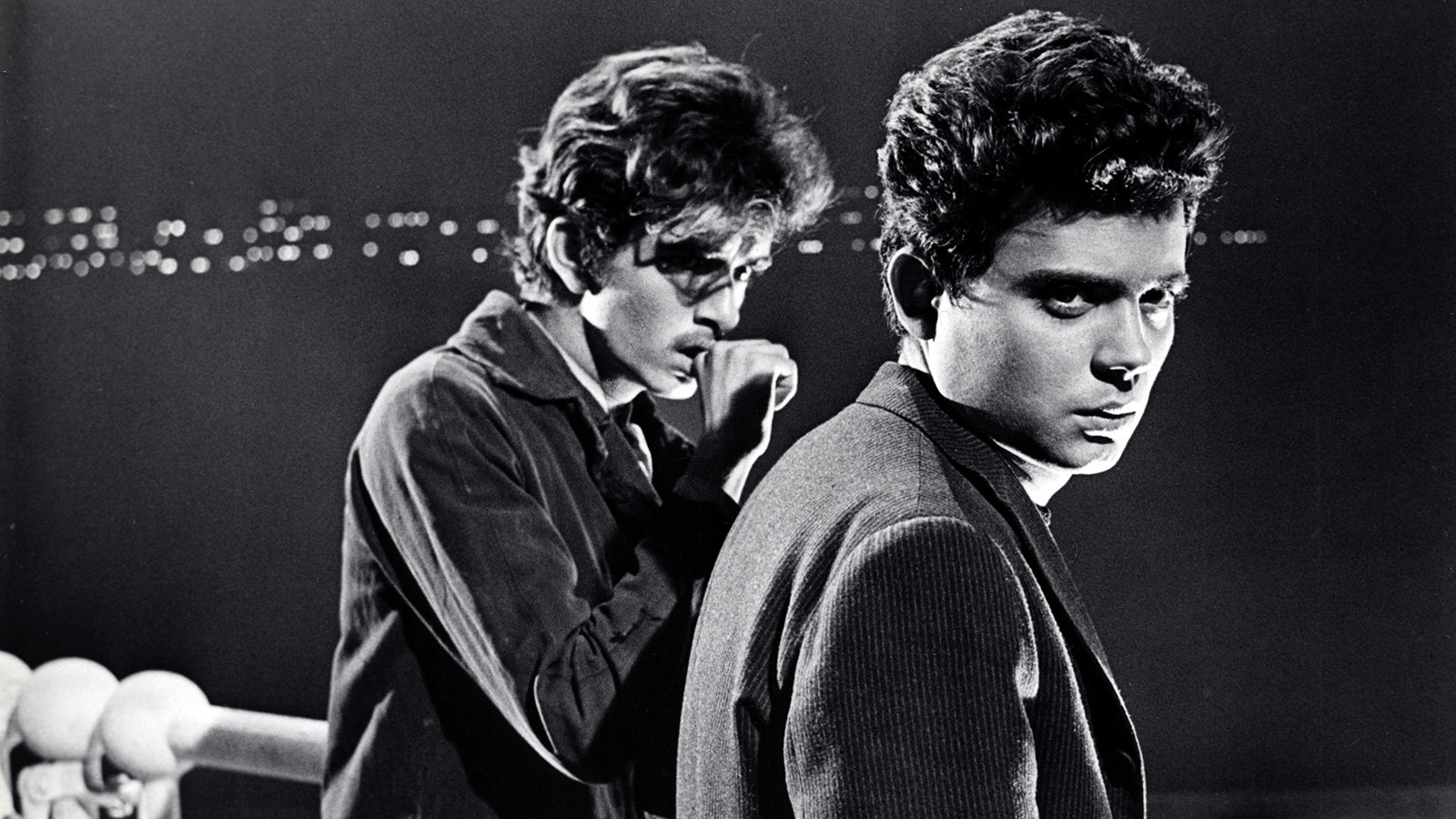

Burl Ives, James Dean, and Raymond Massey in East Of Eden (Elia Kazan, 1955)

More complex than Wild River, East of Eden which was also scripted by Paul Osborn-shares important qualities with that later film in its lyrical lament for the past and its attempt to deal with a period of national social upheaval through the conflicts of the protagonist. Set in 1917, the film evokes an age of innocence filled with romantic myths about war and patriotism which were soon shattered by the casualties of World War I. The dramatic subject of the film is Cal Trask’s increasingly intense confrontation with the harsh realities behind personal myths about his family. But while Kazan is bent on cutting through myths, his nostalgia for lost innocence (an important element in Wild River, as well) is suggested through his affectionate, slightly idealized depiction of the past.

Most of Kazan’s work up to this time had been firmly rooted in realistic detail and staging. He abandoned this in East of Eden for an audacious surrealism, a style whose own extremes appropriately met the demands of the idiosyncratic and reckless protagonist and the psychological depth of the writing. The film is composed entirely from Cal’s point of view: the bizarre camera angles, menacing shadows and images that dislocate and disorient us are the objective correlatives of the protagonist’s young, brooding, imaginative mind which views the world in nightmarish images with a mixture of fear and fascination. The boy’s changing moods are transmitted through sharply contrasting chiaroscuro images. We are immediately struck by the pale, dream-like quality of the film in its opening sequence, where Cal stalks his estranged mother through the town, determined to discover his origins.

In East of Eden Kazan comes closest to realizing the emotional power of intimate, familial relationships which give his films such intensity and are a major theme of his most personal work. The tortured relationships between father and son and between brothers (Viva Zapata!, On the Waterfront, East of Eden, Splendor in the Grass, America America, The Arrangement) represent the kind of confined and intimate arena in which Kazan works best. His most arresting protagonists, like Cal, spurned by his father, suffer from conflicts arising from their intense family ties.

Cal’s agonized gestures are the visual symbols heightening the fury and anger of all Kazan’s central figures-the alienated heroes who stand as the most distinguishing characteristic of his films. No director or recent times has given us such a gallery of magnetic, sexually dynamic men. They are usually characters without much education-outsiders, loners, but people of great energy and drive, great charisma. These heroes are deeply confused, uncertain how to express their longings and frustrations, often struggling to commit themselves, to channel their great passion for life into some socially constructive action. Kazan has captured the inarticulate, defiant protagonist in A Streetcar Named Desire, Viva Zapata!, On the Waterfront, East of Eden, A Face in the Crowd, and America America. In their undirected anger, these characters reflect the deepest form of rebellion against society. These intense figures with their semi-articulated sounds and gestures, sometimes even paralyzed by the force of their anger and frustration and their inability to understand their own confusion, are the perfect metaphor for Kazan’s concern with the individual’s search for his identity. At the same time they effectively represent a repudiation of the values of society; their anger is often a recognition of society’s moral failures-primarily its dishonesty-issues which have absorbed Kazan throughout his career. The torment of characters like Terry Malloy (On the Waterfront) and Eddie Anderson (The Arrangement) results from their recognition that they have compromised and sold out to a corrupt system. On a more personal level, their inarticulateness springs from an inability to adjust the force of their personalities to the conventional structures of society.

For Cal Trask and Terry Malloy, frustration and the struggle to express themselves in words spring from a bewilderment at the way life has dealt with them. Their sensitivity and vision of truth have immobilized them. By contrast, Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire-like Steve Railsback’s Sergeant in The Visitors—represents the more destructive potentialities of the primitive, inarticulate hero. Stanley’s brutal conquest of Blanche, triggered by his suspicion and hatred of her fragile, poetic vision of life, dramatizes a lust for power that will reaffirm his manhood. Cal in East of Eden has moments of cruelty, too, though they are scarcely comparable to Kowalski’s. Despite his occasional vindictiveness, we are attracted to Cal because he is at the same time so passionate and obsessed with feeling, and because he pleads for the truth. Terry Malloy is equally committed to the truth, and like Cal, afflicted with a vulnerability despite his tough, wise-guy exterior. Both young men nurture a deep anger toward father-figures who have betrayed them-Terry towards his older brother Charlie who should have looked out for him but abandoned him, instead, to racketeers, and Cal towards his father who denied him love and fed him lies.

Kazan’s heroes are not intellectuals. But their directness and immediacy do not make them simple figures by any means. They are complex in motivation, and surprisingly paradoxical-alienated on a personal level but often drawn towards conventional success out of their need to establish their identity. The two young men, Cal and Terry, hate themselves for what they think they are. Terry confesses that he is nothing but a bum; Cal, that he is quite simply “bad.” Ironically, they are driven back into the society they have rejected because of their desperate desire to transcend this self-image. Cal succeeds in reconciling his conflict with his dying father, accepting and forgiving him; and Terry achieves the dignity and stature he has hungered for through his dramatic triumph over the forces of evil which John Friendly embodies.

Andy Griffith in A Face In The Crowd (Elia Kazan, 1957)

In an attempt to transcend their humble origins, Lonesome Rhodes in A Face in the Crowd and Stavros Topouzoglou in America America become obsessed with their identity and with the quest for success. While they are on the road, they have integrity and prize their independence, but as success seems imminent, they abandon themselves to it. At the end of America America Stavros, winking at us and flipping a silver coin, indicates that he has learned how to play the game, how to “con” people to get ahead. By the end of A Face in the Crowd Lonesome Rhodes has succumbed to his image of success and has been destroyed by his own delusions of power.

Like Kazan’s male protagonists, the leading women characters in his films possess a striking individuality. These unusual and complex portraits are a startling departure from the majority of females depicted in American cinema. Women in American films are usually punished for exercising power, but Kazan applauds the women in his films because of their strength.

Unlike their groping, verbally paralyzed male counterparts, the women are amazingly adept at articulating their conflicts as well as those of the heroes. These women are not always worldly, but they are surprisingly insightful about defining their own desires and they serve a crucial dramatic function in clarifying for the troubled heroes their strengths and weaknesses. Abra in East of Eden forces the self-pitying Cal to stop crying and brings about the final reconciliation between Cal and his father; Carol in Wild River, who is as unsophisticated as Abra, tells the city-bred progressive thinker, Chuck Glover, what he is and why he needs her; Edie in On the Waterfront urges Terry to confront the moral implications of his destructive association with John Friendly; and Gwen in The Arrangement assaults Eddie Anderson with her fierce honesty that sees through the phony trappings of his bourgeois life and delivers mocking rejoinders to him of what he might have been. Occasionally the women are the real rebels, deriding the conventionality of the men, like the proud madam, Kate, in East of Eden who scorns the pious self-righteousness and domesticity of her dull husband; the irreverent Gwen who dares Eddie to match her audacity; and the eloquent Ella Garth in Wild River, who defies the entire United States Government.

After nearly two decades of translating the work of other writers, Kazan at last became the author of his own films. He had begun gradually to develop control over his productions when he formed his own company, newtown productions in the Fifties, and his collaborations with the writers of his later films, like Budd Schulberg, became increasingly intense. But it was not until America America (which Kazan drafted first as a screenplay, and later published as a novel), that he achieved total control as producer, director, and writer. Ironically, attaining creative control at last seemed to mean little in terms of securing an audience for America America or The Arrangement. The fact that both films were basically autobiographical must have been doubly painful to Kazan. It was a repudiation by the public of what seems closest to him : the impact of his Greek heritage on his life and career, and his private obsession with the question of success.

In The Arrangement Kazan’s conflicting goals—his desire to tell a personal story while at the same time believing he had to make it commercially viable—seemed to work to destroy the film. Part of the failure of The Arrangement was due not to the fact that Kazan had given too much of his personal life, but that he hadn’t given enough. While he had dealt with the central moral crisis of his career, his ambivalence towards success and the destructive compromises necessary to maintain it, he had provided dull, artificial contexts for this crisis—the world of advertising with which he had no immediate contact, and the sumptuous bourgeois life he has avoided in his most impressive films. It was an artificiality that smacked of the conventional urban films which first brought him attention in this country.

Faye Dunaway and Kirk Douglas in The Arrangement (Elia Kazan, 1969)

Like many of his protagonists, Kazan wants to remain true to himself. But he is also driven to win public approval, and like many of the directors of his time Kazan has suffered from the pressure of having to maintain a mass audience. One of the consequences of this tension can be seen in the dramatic resolutions of a number of his films, the need to satisfy popular tastes with something uplifting. (Perhaps one of his more apparent limitations as a director is his difficulty in offering endings that are dramatically satisfying.) Throughout much of his work Kazan has maintained an ultimate faith in the ability of the individual to overcome even the darkest obstacles of his life, and his earlier works were marked by a final patriotic affirmation of American institutions, with the hero triumphing over social evils. In this respect Kazan’s work is representative of other major American directors who similarly affirmed their faith in America with their optimistic endings. But even Kazan’s later films, which have a sense of bitterness and complexity lacking in his early work, often end with the implication that the most crucial conflicts can be resolved for the good of everyone.

East of Eden, which deals with one of the most disturbing images of adolescence we have seen and presents Cal not merely as a troubled teenager but as a tormented being, finally dispels its sense of doom in a sentimental, albeit moving, reconciliation between father and son. Splendor in the Grass presents an essentially tragic vision of youthful destruction only to resolve itself with a spiritually uplifting ending in which the heroine surmounts her tragedy and rises to dignity and maturity. In On the Waterfront one individual amazingly has the power to cleanse an entire system ; and in A Face in the Crowd, Lonesome Rhodes, the symbol of the evil seductive powers of the mass media, is finally overwhelmed by the forces of goodness and reason.

(Two of Kazan’s financial disasters, Wild River and America America, were marked throughout with a more bitter tone than Kazan’s other work, and they were without hopeful resolutions. This may explain, in part, their failure with American audiences. Unlike East of Eden, a popular success, Wild River offered no comfortable solutions to its conflict; and America America comes to a cynical conclusion about the price of survival and the realities behind the American Dream.)

Kazan seems torn by tensions. Many appear to be rather classical Hollywood conflicts that spring from the pressure to survive as a film artist in this country. One is struck, for example, by Kazan’S ambivalence towards America which emerges in much of his work. On the Waterfront and A Face in the Crowd contain an element of contempt for the ignorance and cultural vacuity of the masses of Americans. Yet much of Kazan’s work is a celebration of American ideals. Kazan has been attacked by the right as well as the left and these assaults from both directions seem to illuminate the ways in which he is torn. He counters attacks from the right by defending films like Viva Zapata! and Wild River as pro-American and democratic:

I’ve done more films about social issues in America than anybody. I don’t see what films they’ve made that say anything. Look at the films they’ve done, and what have they done? I’ve made more films that deal with America by myself than all of them put together. They despise America, or seem to. I think America is in terrible trouble and difficulty now. But I think it’s a wonderful country.

These ambivalences—the sentimentality about Americana, yet the strong strain of social criticism of American institutions and myths—really make Kazan’s films remarkably revealing of changing social attitudes over the past 25 years, and at their best, give his work a dramatic intensity that has the power to move us.

Estelle Changas, who served a fellowship year on the rating board of the MPAA, has recently completed her M.A. at UCLA’s film school and writes for various publications.