Camera Man

Jane Pincus isn’t yet sure how she feels about all this... exposure. By now, hundreds of people have watched her take showers, undergo gynecological examinations, argue bitterly with her husband, curse and whine. Soon, I think, thousands will. Already, people recognize her on the streets of Cambridge, Mass., people who know what she looks like with no clothes on, people who know the history of her adulteries and her conflicts with her father. Naturally, it’s a little disquieting. Jane isn’t a movie star, exactly; she’s a movie character—the main character in an extraordinary new documentary by her husband, Ed.

I must warn you: Ed’s film is three hours and twenty minutes long. Worse still, it’s called Diaries (1971-1976). I know, I know: the whole idea makes me yawn, too. Who hasn’t suffered through many a cinéma-vérité “study” of somebody’s uncle’s funeral or somebody’s cousin’s wedding or somebody’s meditative walks down sundry rural lanes? Such movies may shed new light on American rituals; they may force us to examine the hitherto unexamined corners of our lives; but most of them are pretty damned boring.

Not Diaries. In fact, that’s what’s most mysterious and fascinating about it. Its hold on our interest raises all sorts of questions about how movies and narrative and characterizations work. In filming, as best he could, five years of his life, and then editing twenty-seven hours of footage into an evening’s viewing, Ed Pincus has created a comic melodrama of family life in the Seventies that’s as engrossing, saddening, maddening, and haunting as any fiction. He has taken a magical leap, vaulting over the heads of cinéma-vérité and cinematic storytelling into a dazzling new realm.

Not that Diaries ever leaves the realm of the ordinary. The first thing one must deal with in this film is the question: Why look at this stuff? Who cares about Ed Pincus’s life, or yours or mine, for that matter? Even though it is faith in the ordinary that has sustained so much contemporary domestic melodrama—and so much cinéma-vérité—no one really wants to watch someone else’s home movies. Nor is Ed Pincus’s life exactly brimful of incident. A 42-year-old resident of Cambridge and rural Vermont, Pincus is the author of Guide to Filmmaking (1968), probably the best-selling film-technique manual; and in 1969, he created the Film Section at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Currently a Visiting Lecturer at Harvard, he has made six other films, chief among them Black Natchez (1965), a study of impecunious blacks in a Mississippi town; Panola (1970), a fierce and startling portrait of the Natchez town drunk; One Step Away (1967), a vérité look at a sleazy, struggling Haight-Ashbury commune; and Life and Other Anxieties (1979), a potpourri of footage shot after Diaries but edited before it. Life and Other Anxieties, incidentally, possesses none of Diaries’ magnetism; in fact, although the other films have their virtues, they would scarcely rate Pincus a footnote in the history of the documentary. No, Pincus is best regarded as a sort of Seventies Samuel Pepys, a diarist who gets at the decade of navel-watching and narcissism of his own tiny life.

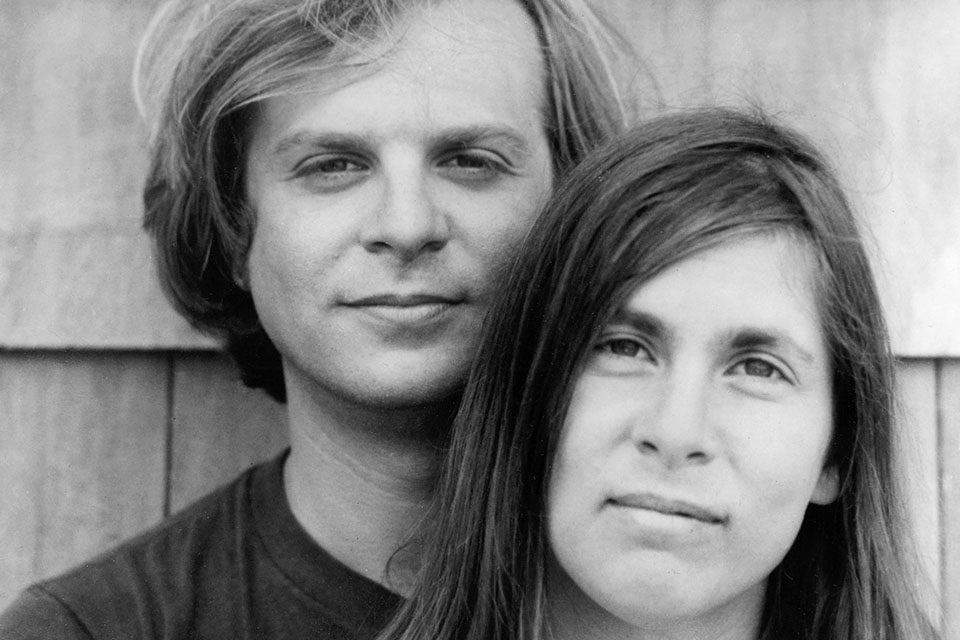

We meet Ed’s wife, Jane, who is 34 as the film opens, their six-year-old daughter, Sami, and their two-year-old son, Ben. Their world looks cozy and funky and sweet (“The happy family,” proclaims Jane, by way of introduction). Very quickly, we realize it is falling apart. The sudden intrusion of the camera may have something to do with that. Like the unwanted guest in a Pinter play, it’s always around when things are getting dicey, and though people try for a while to be polite in front of it, camera manners are soon thrown to the winds.

It seems Ed is having affairs, and Jane, a feminist and a batik artist (and also the co-author of the successful book Our Bodies, Our Selves), is miserable about it. Upstairs lives Ann, a provocative, flirtatious woman who appears to be the object of Ed’s ardor (we later discover that she and Ed have never managed to consummate their little adultery). The tension mounts—soars. Ed and Jane take a trip to California, where Jane weeps by a river and Ed, with unwitting cruelty, tells her she should see Godard’s Contempt. She returns to Massachusetts and Ed takes a frightful mescaline trip, which he doesn’t film (though some of his spaced-out musings find their way onto tape). Back in Cambridge, Jane decides to get a tubal ligation, changes her mind, gets pregnant, and has an abortion. There is a peaceful anti-Vietnam demonstration and shortly thereafter a violent one.

Relations between Ed and Jane deteriorate. He moves into a loft in his MIT office, and returns. There are horrendous, hilarious discussions, the sort of discussions that intellectuals everywhere had in the early Seventies: intricate dissections of what men should be and what women should be, of how relationships should work, of constrictions and, especially, “space.” Not the least of Diaries’ virtues is that it’s a documentary of ethics, a record of the queasy moral soul-searching that for many years turned every sexual act, every flirtation and peccadillo into a socio-political statement. Typically, Jane analyzes—analyzes everything: her body, her reactions, Ed’s sexuality, even the reasons she sneezes. And typically, Ed tries to hide behind his camera, behind manly ratiocination and manly shrugs. Meanwhile, the children play and grow, and so does a dog named Tapper.

Ed and Jane rent a home in Vermont and decide to move there, and when Ann visits them, they attempt a ménage à trois. In one funny, squirmy scene, Ann and Jane sit across from each other like opposing queens, analyzing Ed’s sexual performance of the night before (not, of course, on the basis of its skill; rather on the basis of its political implications); meanwhile, Ed sits on the floor, the third point in this uncomfortable little triangle, and accuses his wife of being “incredibly critical.” Before long, Ed and Jane are seeing a woefully inept marriage counselor, and Jane has an affair with a fellow named Bob. Not to be outdone, Ed takes up with a lissome filmmaker named Christina. As for Ann—well, she disappears from the film altogether, and with her a good deal of strife. We see more of Vermont, of contentment, of children. Jane and Ed look better together. They like each other more—you can see it. The endless, earnest discussions give way to a winking playfulness; the camera often seems to be caressing Jane. And life and the stories it generates plod on. A friend of Ed’s goes mad. Another dies of cancer. The dog grows.

It all sounds desultory and rather vague. Yet, watching Diaries, one is struck by two interdependent sensations: that Pincus’s film is at once exactly like home movies and much, much more exciting than home movies; and that Ed’s life on-screen is limited in a way that real lives seldom are. No one has as few friends and acquaintances as the Ed we see on-screen, nor as little professional life. In fact, only fictional heroes do, because coherent fiction is more easily achieved when the cast of characters is limited and the amount of workaday detail minimized. This, then, is a diary that’s compressed like a fiction: it gives us five years in one sitting.

Ed Pincus and his wife, Jane

In stretching so little material over such a wide expanse, Pincus has made the skin of his film feel taut and resilient. Jumping from one half-sketched incident to another, the viewer begins to fill in the gaps, and the feeling that imparts is rather like suspense. It’s as though Diaries were eliciting some unconscious narrative impulse—a blurring, connecting power not unlike the persistence of vision that turns still photos into moving film when they are flashed twenty-four times a second. Refreshingly, Diaries doesn’t insist on its narrative. The story simply forms, coalesces, as mysteriously as frost on a windowpane. What’s astonishing is that there is a story, that when looked at in pieces like this, life does yield narrative, replete with its own motifs and twists and sequences of suspense. You can see it happen.

One is reminded, of course, of the Louds, that ruddy-cheeked American clan who, on the PBS cinéma-vérité series An American Family, crumbled before the camera’s eyes. But this is different. The difference is that Ed is the camera and the camera Ed. And so the camera—or rather a new creature one might call the camera man—becomes the film’s main character.

This, of course, breaks all the rules of cinéma-vérité. Ever since Jean Rouch’s first experiments in the late Fifties, vérité has held as its holy of holies the dictum that cinema, in Pincus’s words, “must capture the flow of reality independently of presence of the camera.” One needn’t invoke the Heisenberg uncertainty principle to demonstrate that the cinéma-vérité attempt, so defined, is well-nigh impossible, and that the more one hews to it, the more one is creating a dishonest cinema and passing it off as the truth. Far better that the camera not pretend to be invisible, that it admit to its own rather smug personality and presence.

I’ve been talking lately with people whom I think of as techno-determinists—who like to believe that, say, Star Wars was caused by the development of computerized special-effects techniques, or that film noir resulted from new portable equipment that made it possible to shoot amid the gloom and claustrophobia of real city streets. I sympathize with that viewpoint—it’s always seemed to me that the completion of the Empire State Building in 1931 somehow made King Kong not only feasible but inevitable in 1933—but I can’t buy it completely. Admittedly, the Diaries would not have been possible without the development, in 1971, of the miniaturized Nagra tape recorder that could fit into a pocket, allowing one person to shoot footage with synchronous sound, yet achieve easy mobility and relative intimacy. One could say, with Christopher Isherwood, “I am a camera”—except that Isherwood, a diarist himself, goes on to talk about being “quite passive, recording, not thinking.” And that is something no man can hope to be or do.

Fortunately or not, any portrait we make is a double portrait: of the subject and of its observer. The existentialists have known this, and have understood man as ontologically distinct that way: he is, and simultaneously he’s aware of it. Moviemakers too have long comprehended their roles as observed observers; witness the work of Hitchcock, Welles, Bergman, Michael Powell, Brian De Palma, et al. But these gentlemen have been forced to express that awareness through their representatives on-screen—through the characters. Fiction is restrictive in that way. Characters can stand for a filmmaker’s self-consciousness, can even discuss it, but they can’t convey it in all its complexity, because they’re made up. They’re filtered through the filmmaker’s artistry.

In 1970, Pincus decided that “the synch-sound filming of people directly from life had come to a dead end. The style had been established over the previous decade and it seemed to portray people as static in time, with a peculiar distance between filmmaker and subject. It all seemed to me to be a betrayal of what I thought people were really all about.” Diaries had been attempted before, by Miriam Weinstein, Joyce Chopra, Jonas Mekas, and Stan Brakhage, but never in a way that seemed a useful analogue of the literary diary, never in a way that acknowledged both the events as they happen and the personality of the diarist. Weinstein, for instance, interviews people in her life. Chopra hires a cinematographer, a device which honors the recording of events but not the subjectivity of the diarist experiencing them. Mekas and Brakhage work without synch sound, so that their records of life are very remote from the way events actually feel; moreover, Brakhage pretends that life and memory are a series of still, uninflected visions, visions that never seem to have touched human consciousness.

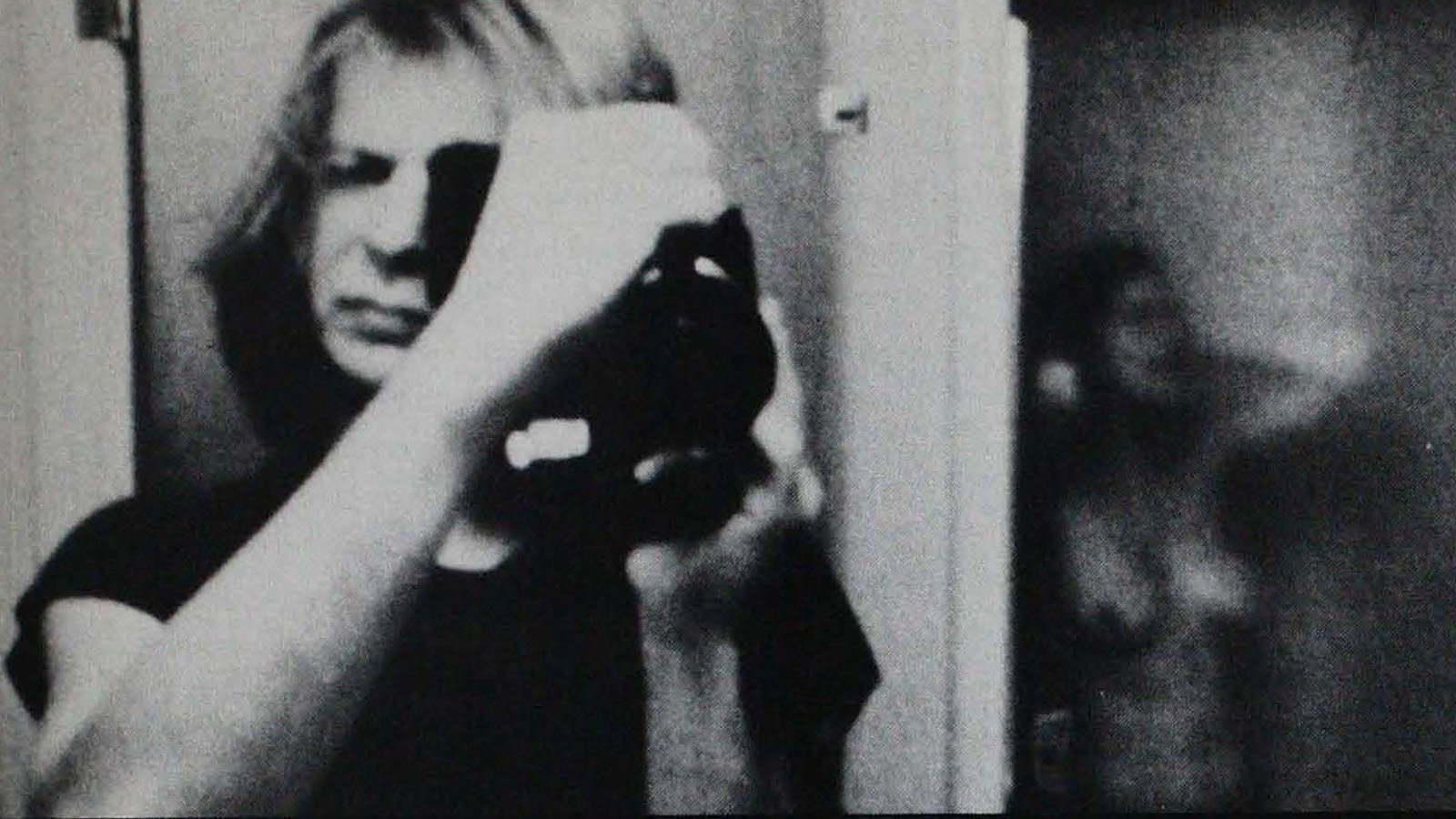

Why, after all, do we read a diary? Not for a simple record of events, or an acknowledgment of time’s passage, or mere interpretation, either. We want both, the record and the sensibility. But if a literary diarist sits down at the end of a day and records and interprets what has happened, a cinematic diarist has many options. I emphasize this because I think Pincus has chosen the best. If he is truly to record, truly to capture life’s flow, the cinematic diarist must turn on the camera before he knows what it is going to see; no interviews or planned scenes will do. And if he is truly to interpret, he can do so only in the editing room. Ed Pincus may be the first filmmaker brave enough to have seen that to create a rewarding cinematic diary you must not only bring the camera into your life—you must, at times, become the camera, let the camera live your life with you, and for you.

With a Nagra in his pocket and a 16mm camera on his shoulder, Ed Pincus shows us his world—the observed—and, advertently or not, he shows us who he is as well. There are those who have seen the film and accused Ed of leaving himself out of it, of being evasive, of letting himself off various moral hooks. But this is to look only at Ed the character, not at Ed the camera. Standing behind his Eclair, being yelled at by his wife, being taunted by his mistress, being delighted by his kids, and replying or laughing or agonizing in a voice that begins to sound as though it’s coming from the back of our own heads, Pincus becomes an astonishingly full-bodied presence. His life and soul are on display as those of Hitchcock and Welles, or even such baldly autobiographical filmmakers as Fellini and Woody Allen, never are. To be sure, the life and soul of Ed Pincus may not be as rich or as fascinating as theirs. But what surprises me is how thrilling it is to see so deeply into anybody, even into such an ordinary, mixed-up man. Watching Diaries, one encounters a new astonishment at the art of cinema itself, at its world-redeeming power—an astonishment that must be rather like what the viewers of the Lumière films felt, looking in awe at a picture of trees in which they could actually see the leaves move. In the Diaries, you can see relationships move, and psychologies; you can see the dance of time itself.

How do we discover Ed Pincus through his film? The answer lies partly in that gap between the act of recording and the act of editing. The Ed who records is a different man from the Ed who edits, and the latter has the luxury of time and distance. That time and distance lend the film its moral authority; Pincus the filmmaker can judge and even condemn Pincus the character. The situation resembles the one in fiction, where we judge characters as their creator does. But Diaries offers a freedom that good fiction doesn’t: the freedom to disagree.

When Gary Cooper tells Jean Arthur she’s beautiful, who will not concur? The director has seen to it that the make-up artist and the backlighting and the focus and the position of her face make Jean Arthur as beautiful as she can be—and casting her in the first place ensures our agreement. But at the beginning of Diaries, when Ed tries to reassure his nervous wife that being on camera is OK, he tells her she’s very beautiful, and though Jane is certainly attractive enough, I am struck by the sensation that I can disagree, that in recording his life through his own subjectivity, Pincus has abdicated the filmmaker’s traditional control over our perceptions. The scene goes on. Jane admits to feeling judged. From behind the lens, Ed tells her she’s not being judged—and somewhere in that statement, we feel a lie. When we do, and when we refuse to agree that Jane is beautiful, we are also judging the filmmaker; we are discovering who Ed Pincus is in how his views and perceptions differ from our own.

Another example. There is a boisterous, funny short story within the film called “South by Southwest,” a twenty-minute segment during which Ed visits his pal David Neuman (who co-directed Black Natchez, Panola, and One Step Away), and the two of them drive from Los Angeles to the Grand Canyon to Santa Fe to Las Vegas. Neuman is a raffish, antic, hippie-ish sort, and a crafty manipulator of the camera. Joking and mugging and telling tall tales about his sexual exploits, he turns himself into a great comic character, one the viewer realizes is a composite of lies, postures, and distortions. I love this sequence, partly because I find David engaging and partly because Pincus has allowed his friend to become something of an alter-ego. David reflects a side of Ed that can’t come through in the earnest Cantabridgian discussions with his wife and other liberated women: the nasty, boyish, jubilantly macho side. David plays off the filmmaker, squeezes delighted giggles from the voice behind the camera, even cleverly draws Ed into the film by suddenly treating the camera as though it were a man instead of a recording machine. “South by Southwest” is one of the brightest, most ebullient sections of the film, and much of that brightness is in the way the camera moves, in its choice of what to look at, in its mood.

The first-person cinema is nothing new, of course; one recalls a moment in Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera when the camera itself comes to seem a man taunted by ladies in a taxi. And there is that mammoth folly, Robert Montgomery’s Lady in the Lake, in which we are supposedly observing everything through the eyes of the detective hero (seen only in mirrors), who is subjected to a wide array of onrushing fists and faces and puckered lips. The silliness in Montgomery’s experiment, and in all the subjective-camera work in such recent horror pictures as Halloween, lies in the fact that the camera doesn’t act like a person, doesn’t see like one or move like one. Pincus’s camera can’t help moving like a person and seeing like one; it practically is one.

The late phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty believed that a man expresses the whole of his being not just in what he says and does but in the minutiae of his movements, in the way he gestures, the way he travels through the space of a room, even the way he throws his glance upon a distant object. The movements of Pincus’s camera convey who he is as surely as any intentional action, and by watching them, we discover him as an auteur in a way that we never could discover Hitchcock or Welles or Ophüls. This is a mysterious process, but it needn’t seem so obscure. Pincus’s skill at frame composition, for instance, fluctuates throughout the film, depending not only on his subject (it’s harder to compose a violent fight with your wife than a portrait of her taking a shower) but also on his state of mind. The calmer and more confident Pincus is, the prettier his shots. The film ranges from raw, jagged footage, shot mostly in raw, jagged Cambridge, to the careful, painterly, contemplative views he gives us of his Vermont home. As he and Jane mature, as their troubles subside, the cinematic style grows more precise and even picturesque. (Also a bit duller, though audiences seem more relieved than bored.)

In one scene, Ed’s son, Ben, tries to use the Vermont outhouse on a particularly chilly day. “It’s cold, Dad,” he complains to the camera, and we hear Ed adjuring him to sit on it anyway. In the midst of this scene, a fascinating thing happens. Ben becomes distracted by something; he keeps looking up beyond the upper right-hand corner of the frame. Very quickly, we become curious about what it is he sees there—we’re conditioned, no doubt, by the traditional three-shot syntax: the shot of the character’s looking at something, the shot of that something, and then the shot of the character’s reacting to what we’ve seen. Here, any fiction filmmaker would immediately cut to the object of Ben’s interest. But the camera stays on Ben, because the camera is not a story-telling device, it’s Ed—and Ed, at that moment, is feeling tough and paternal and refusing to be taken in by his son’s cute evasions. Finally, Ed relents, and the camera pans to show us what Ben’s been looking at, anticlimactic though it is: a little bird perch. Then quickly, almost sternly, it whips back to Ben, the boy who won’t go to the bathroom. That little sequence says more about fatherhood than all of Kramer vs. Kramer.

Ben Pincus in Diaries (1971-1976)

In fact, there’s a lot that the makers of fiction could learn from Diaries. They should note, for instance, the way the characters behave perfectly plausibly, yet without that time-honored device known as motivation—that motivations are never as present or as clear in real life as they are in fiction. They should also note the way moral questions are worked out through the characterizations; in this, Diaries is as skillful as any Western or gangster film.

Actors ought to see the film too, to examine the subtle gestures and shifts of tone by which Jane manipulates Ed or makes herself attractive to him or defuses her children’s anger and rambunctiousness. They ought to study the portrait of an erotic feminist concocted by Ann, and they ought to see the funky New York chic of Christina. (Pincus manages to bring a real glamour and allure to each of his women. He may be the Von Sternberg of the documentary—or at least the Charles Vidor) Bruce Dern, Anthony Perkins, and other actors accustomed to playing psychotics ought to take a gander at Dennis Sweeney, whose appearance in Diaries summons a chill that deepens as the film progresses. Sweeney had been a Civil Rights organizer who appeared in Pincus’s Black Natchez, and when he shows up in Ed’s kitchen in 1972, talking quietly about the dreadful voices he hears in his teeth, I recognized him at once from newspaper stories: this is the man who would later, in 1980, kill Allard Lowenstein. Nothing I know of in fiction or documentary feels the way that moment feels; no foreboding is so palpable.

Of course, a certain amount of narrative structure seems born in the editing room. The film begins when Ed is about to attend his uncle’s funeral; it nearly ends with the death by cancer of his friend, filmmaker David Hancock; in between there are several contemplations of death. Indeed, almost everything in this movie begins to comment on everything else. A game of freeze tag among the kids becomes a metaphor for being caught in the cinematic frame; a scene in which Christina eavesdrops on her neighbors’ marital strife becomes a metaphor for the film’s eavesdropping on Ed’s; Ben, who cuts his finger shortly after his father does, comes to seem a metaphor for Ed, reflecting his fears and hesitations and depressions. And so on.

What is exhilarating in Diaries is not the way it creates such felicities but the way it finds them. There is an argument between Ed and Jane in a car on a drizzly day; the windshield wipers flap back and forth, intruding on the sound, deadening the atmosphere (an apposite alienating device). Jane is very upset, and the conversation bursts with that anger-cum-analysis so redolent of the Seventies. “You’re sitting placidly on your defenses,” Jane says. “You run away from intimacy.” Then, surprisingly, she launches into an explanation of why she sometimes sneezes during their discussions. It comes from “absolutely not being able to say I need you… I’m being hostile in some way and at that point, I sneeze.” The insight is accepted and forgotten. But several scenes later, Jane is sitting naked and blithely telling Ed about her new lover, and suddenly she sneezes. That sneeze is motivic, fiction-like but real; it shatters the barriers between story-telling and life.

I make great claims for Diaries, and yet I rather wish that others wouldn’t try to imitate it. Ed Pincus has created a marvelous film, and I hope it’s an influential one—but not as the spearhead of a new genre. That genre would only repeat itself, would quickly overrun and settle the lush border country between truth and fiction, posture and persona. And it would surely erode the force of its progenitor. Better that Diaries be seen, and seen widely, that it be taught and studied and cherished—and then let go, like the past it so perfectly evokes.