Do You Hear What I Hear?

In Sergei Loznitsa’s State Funeral, Soviet citizens congregate throughout the country in March 1953 to honor the passing of the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin. Entirely archival, the footage for the film derives from a movie called The Great Farewell, which draws on dozens of filmmakers who captured the four days of public mourning that followed Stalin’s death. That early film had been shelved and was scarcely seen until the ’90s, whereas Loznitsa’s premiered in September in Venice before coming to North America for the Toronto and New York film festivals.

State Funeral gathers that raw material, shot on both black-and-white and color film stock, into an effectively linear synchronicity of disparate shoots all witnessing a similar procession of reverence and solemnity: from workers emerging out of an oil rig hoisting Stalin’s portrait—presented as if it were a religious icon—to the actual funeral procession into Moscow’s Red Square. Feet shuffle. Flags flap in the wind. Mournful horns echo in the square. Comrades murmur. What you see is an astonishingly well-preserved record of those four days in 1953. What you hear, however, is fabricated.

Sound design in nonfiction can involve all manner of modulation, mixing, approximation, overdubs, and enhancements. Often these manipulations are inconspicuous, affecting the experience of the film without your really noticing. In a few new documentary works—State Funeral and another archival film, Manfred Kirchheimer’s Free Time, as well as Feras Fayyad’s largely observational The Cave—post-production sound plays a more central and detectable role. In these films, there’s meaning, feeling, and even commentary in sound’s presence, absence, and variable volume.

For the most part, sound complements or supports the images in State Funeral, such that (historical-technological impossibilities aside) you could mistake the fabricated sound cues for real ones. There’s a hush that presides over the film, commensurate with images of mass performances of mourning. Yet there are choices that, in the context of a minimalist soundscape, function as directives to the eyes. The sound of a man coughing nudges us to notice the figure lifting hand to mouth within the frame. The sound of a woman crying guides us to a distraught face, watery eyes. Loznitsa’s most overt interventions come in the form of archival audio recordings of honorific speeches commemorating Stalin’s magnificence, presented as if they were playing over loudspeakers, which makes them ingratiate like near-subliminal benedictions.

Or rather, the sound treatment implies they’re playing over loudspeakers, thanks to a tinny, echoey mix that situates the broadcast within the reality of the scene. These recordings may have been commonly broadcast in that manner, but here they’re audial inserts: an effect, and a meaningful one. Loznitsa is coupling spoken-word lionizations of Stalin with images of a populace that had been terrorized and subjugated by him. The spectacle of thousands upon thousands of these comrades trudging through the cold to mourn their tormentor plays not as irony but as unspoken, unacknowledged perversity. Everyone in and everything about State Funeral is straight-faced. It’s in the quiet that a critique can be heard—in the things not said, the exhales of relief we might imagine mixing with the sobs of mourning, the dispassionate officiousness with which the ceremonies, and, finally in the last reel, synced eulogies from Stalin’s colleagues play out.

State Funeral (Sergei Loznitsa, 2019)

Like The Great Farewell, Free Time was filmed before portable sync sound became available. But unlike Loznitsa, the 88-year-old Kirchheimer is revisiting black-and-white footage he himself shot with collaborator Walter Hess 60 years prior. Regardless of the original intent, the intervention of time makes the material archival. And now, as then, a lack of sync sound isn’t a deficiency for Kirchheimer but rather essential to his preferred practice. Though he’s also made video-based sync-sound films along the way, Kirchheimer’s most celebrated work (Stations of the Elevated, 1981; Claw, 1968) has been made in accordance with the methodology in which he was originally trained: adding all sound during the edit as needed, and for effect.

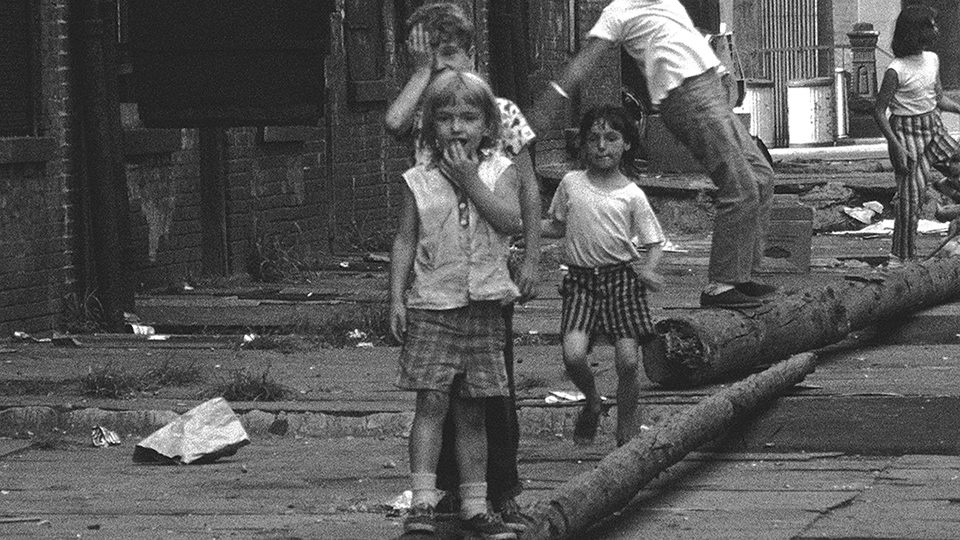

Throughout Free Time—a film that forgoes traditional characters and story for a jazzy montage of exquisitely lensed Manhattan street scenes—musical passages from the likes of Bach and Basie share a soundtrack with select cues: the clatter of a stickball bat dropping to the pavement, an overpacked shopping cart whining down the street, the clanging of a construction site. The mix is minimal, and selective to the point of abstraction. We hear only what’s most relevant to or evocative of what we’re seeing, like an audial iris shot. There are scarce errant sounds, and no cacophonous urban texture. We hear what Kirchheimer wants us to really hear—to accept it as information rather than as noisy persuasion of reality. The director was so deliberate about the meditative, elective audibility of his film that after its world premiere at the New York Film Festival he publicly reflected that he’d wished the sound had been quieter in the theater. In Free Time, you don’t hear noise, you hear notes.

Free Time (Manfred Kirchheimer, 2019)

There’s a different equation and intent in The Cave, Fayyad’s follow-up to his Academy Award–nominated Last Men in Aleppo. As the Syrian city of Ghouta crumbles amidst the ongoing civil war, many citizens retreat underground to a series of tunnels connecting them to comparatively safer spaces, including a hospital managed by Dr. Amani Ballor, a young pediatrician fighting desperately to save lives, often in spite of patriarchal resistance. Visually, The Cave is a raw document. Considering the elements in play, it couldn’t be otherwise, and you wouldn’t dare expect as much. How is anyone here still living—let alone sacrificing their own safety to keep others going amidst the endless horror, let alone making a painstakingly constructed observational film about it? What Fayyad, and in turn the audience, encounters in The Cave is truly, precisely horrific. We see wounded, terrified, dying people, many of them children—which is hard to accept, but also essential to witness.

What’s not raw, what’s resoundingly unsubtle in The Cave, is the sound design, which complements the on-the-fly observational footage with high-end theatrical audio production. Like another very, very different 2019 feature—the high-frame-rate, experimentally structured, water-born thrill ride Aquarela—Fayyad’s delicately intimate documentary portrait is presented in Dolby Atmos. What this apparatus affords, above all, is bracing, jolting, you-are-there volume. Whenever a bomb strikes out of frame—visually signaled by Ballor or another hospital colleague suddenly looking to the ceiling with trepidation—the Dolby Atmos slams in, providing furious, chest-rattling thunder.

The Cave (Feras Fayyad, 2019)

The implication is that this is what it feels like. Sound transports us into the scene, and into the very bodies of the people we’re watching. Sound closes the distance, compelling us to feel the conditions people are living through, to feel the anxiety and dread that pervades and defines their days. And dear lord, do we feel it. Matthew Herbert’s very present score ensures further feelings, all of which left me wondering what qualities of sound engender what kinds of emotions. Do I need enhanced bomb sounds to feel or understand what it’s like for Ballor to hear them? Do others? To be honest, I bristled at times while watching The Cave, not because I was resisting the extremity of what I was experiencing, but because the sonic mix felt insistent where no insistence was necessary. No music is needed to make me feel for people choking back the effects of chemical warfare, no Atmos is needed to sell the trauma of living underground while the world collapses above. Amplifying horror can run the risk of obscuring it, of distracting from the experience rather than deepening it.

But just because I don’t need it doesn’t mean it can’t help. Just because Kirchheimer wants the volume turned down doesn’t mean Fayyad and others don’t need the volume turned way, way up, sonically and morally. And it’s not like Fayyad doesn’t know the power of quiet, which defines the moment in The Cave that affected me the most. After a nightmarish, seemingly endless sequence of triage in which they’re overmatched by the breadth and severity of life-threatening and life-taking injuries, Ballor and her colleague, Dr. Salim, retreat to their small, cramped office, utterly exhausted and, for the moment, utterly defeated, where they softly weep. After the noise of action, we’re left with the quiet of reflection. The shots aren’t perfect—thinking back I couldn’t tell you how they were framed, or if they were even in focus. But I was inside of it with them, sharing a devastating silence.

Eric Hynes is a journalist and critic, and curator of film at Museum of the Moving Image in New York.