Divided We Fall

The story of Third World Cinema Corporation—a fledging production house founded by Black and Latino artists in 1971—is at once inspirational and heartbreaking. An earnest “for us, by us” effort to tell stories the studios would have never picked up, the company staffed its productions with people who had been or would have been systemically kept outside studio gates. Throughout most of Hollywood’s first century, few studios had produced Black- and Latino-centric movies, claiming they were risky or not of interest to general audiences. From the silent era through the 1950s, segregated theaters created an independent market for movies by Black filmmakers for Black audiences, and later, new independent filmmaking efforts arose with the cultural upheaval of the 1960s, followed by the rise of blaxploitation, the L.A. Rebellion, and Chicano cinema. But the problem of representation persisted within the studios, and at a more fundamental level, little was done to promote talent from underrepresented backgrounds.

Then there was Third World Cinema Corporation, an unusual presence even in the much-mythologized annals of independent studios—the rare film company where the board would be led by people of color: actors Ossie Davis, Rita Moreno, Cliff Frazier, Brock Peters; and writers Piri Thomas and John O. Killens. At the height of the blaxploitation era, Black intellectuals and activists had worried that the defining narratives of their communities would center on street violence, prostitution, and drugs. Movies from Third World Cinema (TWC) were to serve as antidotes to those narratives. And Claudine was its success story.

Distributed by 20th Century Fox but produced by the Third World Cinema Corporation, Claudine follows a struggling mother (Diahann Carroll) of six as she hides her income as a domestic worker from the prying eyes of a nosy welfare worker, to make ends meet. She’s more or less given up on love until a friendly garbageman, Roop (James Earl Jones), takes an interest. The movie is remarkable not just for its heartwarming story or Carroll and Jones’s impressive performances; it also includes a pointed critique of a welfare system that seems designed to thwart the couple’s happiness.

Claudine was a preview of the kinds of movies that might have come from Third World Corporation had it survived: heartfelt stories that ditched stereotypes for complex characters. And in terms of representation off screen, fully 28 of the 37 production jobs on the film’s set had been filled by Black or Latino talent. That level of inclusivity didn’t come from a studio mandate—the push came from Third World Cinema Corporation, which set up a training program, struck deals with unions to get their students membership, and helped place many of their first alums into job opportunities once thought to be closed off to them. On its release in 1974, Claudine went on to find a sizable audience, earning $6 million at the box office, or roughly $31 million today.

Third World Cinema Corporation had been founded by Davis with Hannah Weinstein, a producer who had fled the States because of McCarthyism. Davis became the company’s President, and Frazier—an actor turned activist after the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—was appointed to be the Administrator over the training program. When Davis announced his new initiative to establish a production and training studio, the news of a “minority-run” film company with a distribution deal through a major studio earned headlines in The New York Times, The New York Post, and Variety.

Frazier, one of the last surviving board members of TWC, recalled the significance of the commercial and critical appreciation in a recent interview: “It gave us a prominence that we had never achieved before. Whites collaborating [on] a Black film and not controlling it.” Carroll earned Oscar and Golden Globe nominations for her performance; Jones also picked up a Golden Globe nomination, as did Curtis Mayfield’s song “On and On.” A handful of the first TWC training graduates worked on Claudine, like assistant cameraman Audley Simpson and assistant editors Sharon Brown and Carey Beth Cryor. (Success, however, did not guarantee a future for the rank and file. As Simpson would tell the Times in their report on his graduation from TWC’s program, he found only blank stares when he looked for union jobs: “Right now, man, it’s all glamorous,” he said, ”But what happens to me after Claudine? Will I get another job?”)

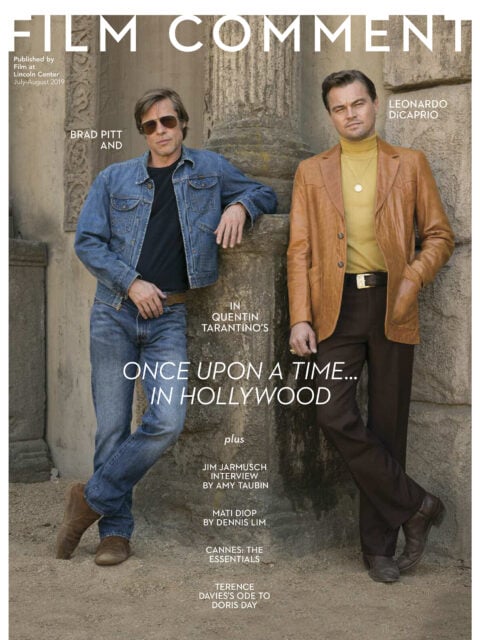

Diahann Carroll and James Earl Jones in Claudine (John Berry, 1974). Courtesy: Everett Collection

When Third World Cinema Productions was first announced, Davis said he anticipated producing five feature films in the next two years. One was to be a biopic of Billie Holiday starring Diana Sands, although the untimely death of the actress (who had also been originally cast as Claudine) and the success of the 1972 Diana Ross vehicle Lady Sings the Blues essentially nixed the idea before it went into production. The June 1972 issue of Black World anticipated the TWC screen adaptations of Puerto Rican writer Thomas’s Savior, Savior, Hold My Hand starring Rita Moreno, with Davis slated to direct, and Killens’s And Then We Heard the Thunder. A 1974 dispatch in The New York Post claimed that an adaptation of Thomas’s later book Seven Long Times would be directed by fellow Puerto Rican Jose Garcia. At one point, there was also talk of TWC purchasing the Filmways studios in Harlem.

The company’s eventual follow-up to Claudine was the biopic Greased Lighting, about one of the first Black stock car drivers in NASCAR, Wendell Scott, starring Richard Pryor and Pam Grier. But reviews were middling and the 1977 film did not earn much of a following. Weinstein produced both Claudine and Greased Lightning—but the next Pryor film she produced, Stir Crazy, was not made for TWC. In 1975, an article in the Amsterdam News was wondering if the wheels were coming off the once-promising company. Third World Cinema produced one last film in 1980, a documentary on painter Romare Bearden for PBS called Bearden Plays Bearden. James Earl Jones returned to narrate Nelson E. Breen’s film, which also involved the participation of James Baldwin, Alvin Ailey, and Ntozake Shange.

Various factors led TWC to cease production, the most popularly cited reason being that the city’s political winds had shifted, cutting off grant money and stifling union jobs. At its inception, the company received a $200,000 grant from the U.S. Manpower Career and Development Administration and a $400,000 grant from the Model Cities program, but not enough private funds came forward to keep operations going. “Money ran out,” said Frazier, who today runs the Harlem arts nonprofit Dwyer Cultural Center, much of which is dedicated to the legacy of Davis and Ruby Dee, his partner. According to Frazier, the TWC isn’t quite dead, only absorbed under the umbrella of the International Communications Association, which was established in 1986 to also include the Community Film Workshop Council and Institute of New Cinema Artists, a training organization. It has since taken decades for Hollywood to adopt or adapt TWC’s training program model, and not all of these programs guarantee work at the end of their completion. Today, most studios and major networks have some form of diversity or inclusion efforts in place, like the Universal Writers Program, HBOAccess Fellowships, or Warner Bros. Television Workshop. Guilds and agencies have also stepped up their diversity initiatives, like the DGA Director Development Initiative and CAA’s new Showrunner Mentorship Program.

Not long after the end of TWC’s run, a new wave of independent Black and Latino filmmakers arrived—Spike Lee, John Singleton, Julie Dash, Luis Valdez and Gregory Nava, to name but a few. However, by the end of the ’90s, progress once again waned until the recent push for diversity and inclusion reignited calls for Hollywood to open up its studio gates (again). Some filmmakers are taking a more active hand in mentoring or independently producing their own projects, with Lee employing NYU students on his sets and Ava DuVernay seeking out women directors on Queen Sugar. TWC’s plan to create a studio just as invested in training and empowering underrepresented filmmakers as it was in independently producing their stories may have petered out, but the core ethos of its mission has yet to fade.

This is an extended version of an article that appears in print in the July-August 2019 issue of Film Comment.

Monica Castillo is a film critic and features editor for CherryPicks. her writing has also appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, NPR, rogerebert.com, and elsewhere.