François Truffaut: Day Into Night

Now that he’s dead, no one will protect you.” So, apparently, said Anne-Marie Miéville to Jean-Luc Godard when François Truffaut died in 1984 at the age of only 52, her words sounding like a sibylline prophecy of how this one death might portend the destruction of a whole house. The warning is recorded in Two in the Wave, a 2009 documentary directed by Emmanuel Laurent and written by Antoine de Baecque, about Truffaut, Godard, and the birth of the Nouvelle Vague. This might be the house in question, though according to Laurent’s documentary it had already brought about its own destruction—as if in a classic Attic tragedy—when Truffaut and Godard had a falling out in the early Seventies. At this moment, “French cinema, at least the New Wave, is shattered,” concludes Two in the Wave.

We also hear Godard’s take on what Miéville had meant: that Truffaut had managed to be “accepted by and tried, in a way, to join the establishment.” This is less apocalyptic, and more or less sums up what had become a common verdict on later Truffaut, that the critic who had once been the terror of old-guard French filmmakers had turned into the modern version of this kind of entertainer.

We can even say that Truffaut’s “protection,” in its most ethereal sense, stretched back to the very beginning, to the bonhomie, romanticism, and larky experimentation of his early films. “Once the Prince Charming of the French cinema,” per Time Out, or “the most accessible and engaging crest to the New Wave,” as David Thomson put it, Truffaut was always the goodwill ambassador of the Nouvelle Vague where Godard was its gnomically provocative spokesman. It’s possible, though, that the pair weren’t quite yin and yang—that they were more complexly nested within one another. It’s possible that Truffaut was more like Godard, or that he was in many ways unlike the “Truffaut” that the above constructions suggest.

Jules and Jim

1. PLANES, TRAINS, AUTOMOBILES & JUMP CUTS

A case in point might be Une histoire d’eau (58), a narrative short that took off from a real event, the flooding of the countryside south of Paris in February 1958. Truffaut shot the original footage but then put it aside, and Godard later took it up to edit and add a breezily divergent commentary. The result is “a strange mixed beast,” according to Two in the Wave, although Truffaut’s “rapid shooting style” and Godard’s idiosyncratic organization seem synchronous enough, batting about the story—and the original news event—like irreverent tennis players (the pair are usually credited as the film’s co-directors).

A final flippant touch—though it’s the real mark of synchrony—is that the film is dedicated to Mack Sennett. Slapstick is a mode of thought in Godard, another way of exploring possibility; in Truffaut, it’s more like a structural principle and a closed system of limited alternatives, both comic and bleak. This is reflected in its own yin and yang duos. Laurel and Hardy might be Truffaut’s favorites: they turn up in Halloween-type children’s masks in Stolen Kisses (69), and even when Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) dubs his wife’s breasts, which he declares aren’t the same size, Laurel and Hardy in Bed and Board (70). Doubles abound in Truffaut, but as matched sets, not in the usually dynamic form of doppelgängers.

The way James Monaco interprets Truffaut’s pairings (in his contribution to Richard Roud’s Cinema: A Critical Dictionary) is in line with a view of Truffaut’s expansive humanism: “these bifurcated personalities offer Truffaut a chance to investigate the dynamics of human relationships, their micropolitics.” But the doubles are really a bit of cinematic magic, a Méliès-eque sleight of hand. Julie Christie’s two characters in Fahrenheit 451 (66)—a long-haired brunette and a cropped blonde, one a duped and doped zombie of the system and the other a free-spirited rebel—might be the fat one and the thin one.

In Shoot the Piano Player (60), Truffaut’s second film after his autobiographical slice of life, The 400 Blows (59), the slapstick schematics really come to the fore: in place of a duo there are four brothers (one called Chico; are they Marxists?); the bashful hero (Charles Aznavour) and Lena (Marie Dubois), the girl he shyly courts, make a nice pair in pale trenchcoats; and the hero himself is two, with a prior life as a concert pianist named Edouard, and his life now as Charlie, playing dance music in a bar. With the slapstick types goes a slapstick speed: have any otherwise conventional narrative films ever moved faster than Truffaut’s, with a pell-mell delivery of dialogue to boot? (Internal commentary, with letter- and diary-writing, also steps up the pace.) His films almost always open with someone on the move, including a long drive with an incidental character at the start of Mississippi Mermaid (69).

There’s a concentrated montage of plane, train, and hovercraft later in the same film, along with a graphic line that travels across a map—a trope that gets more extended, old-fashioned treatment in The Story of Adèle H. (75). Even more old-fashioned, of course, is Truffaut’s liking for such optical effects as the iris-in and iris-out (plus joke cameo inserts in Shoot the Piano Player). The freeze frame that ends The 400 Blows is his most famous technical flourish, but brief freeze frames are the corollary to speed within many of his films. He has said he reduced their duration from 30 to 35 frames in Jules and Jim (61) to 7 or 8 frames by the time of The Soft Skin (64): “I’m interested in invisible effects now.” A suite of quick freezes of a grimacing Jeanne Moreau in Jules and Jim is intended as a “little joke” on Moreau’s roles in films like La Notte and Moderato Cantabile, “where she was always a bit grim.”

Most startling, and piercing, of all Truffaut’s early films is The Soft Skin, because it applies the narrative speed to bourgeois tragicomedy—a middle-aged man’s pursuit of a younger love—wherein the freeze-frame effect becomes taunting. As the hero dashes about, trying to fit his lover into the interstices of his life, Truffaut’s “rapid shooting style” and editing become frantic in their turn. In addition, Truffaut jump-cuts like Godard but in his own idiosyncratic fashion. There are hiccups in what are otherwise lengthy one-shot sequences of domestic wrangles in Shoot the Piano Player (which lead to the suicide of Charlie’s first wife), between the unruly pupil and Truffaut playing his teacher in The Wild Child (69), and between fleeing lovers in Mississippi Mermaid. Godard’s equivalent might be the even longer domestic wrangle in Contempt, cut conventionally but with the eccentric decor of an unfinished apartment as punctuation. The door without a pane of glass that can be opened, stepped through, or both at once almost takes us back to Sennett origins.

The Soft Skin

2. ONCE UPON A TIME

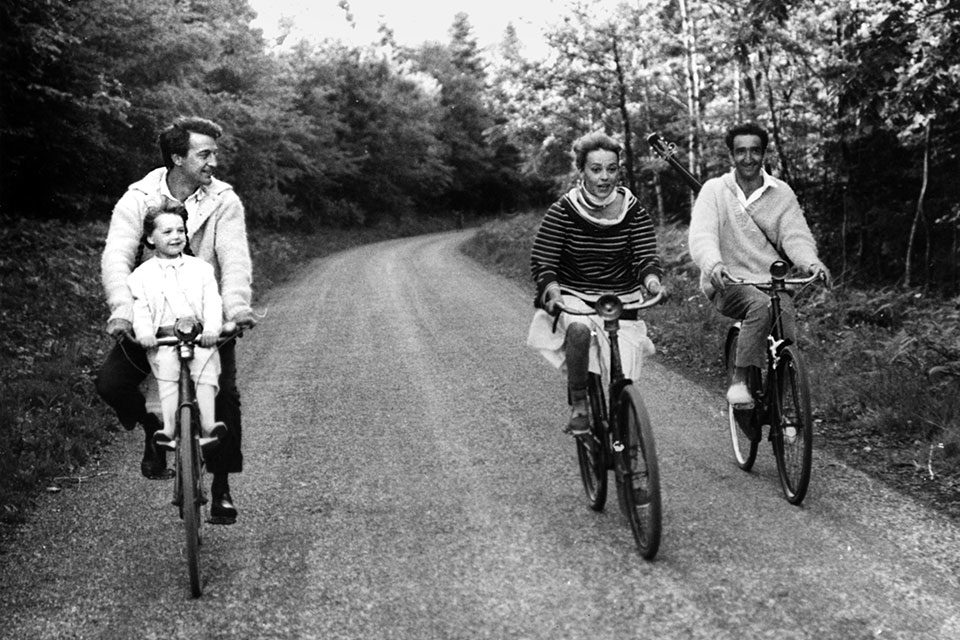

If doubles in Truffaut are more matched duos than true doppelgängers, then other things follow. One is that these figures have a peculiar lack of interior life, even, it has to be said, in Jules and Jim, which for many people remains the exemplary Truffaut in its treatment of romantic entanglement. Jules (Oskar Werner) and Jim (Henri Serre), a German and a Frenchman, seem to become friends in Paris at the moment the film begins, and the inception or content of their friendship is a mystery covered—as often in Truffaut—by busy commentary and the writing done by the characters themselves, the business of cultural production. They “teach each other their language and literature,” and Jim writes an autobiographical novel called Jacques and Julien, in which Julien is a writer (this is complex nesting).

Jules and Jim become doubles when they appear, in identical white outfits, for their visit to an Adriatic island where they find the carved stone head that becomes the image for their mutual inamorata, Catherine (Jeanne Moreau). When Jules and Jim were a pair, “people even thought they were a bit queer,” but with Catherine they find their true public persona as “The Mad Trio.” In fact, Truffaut’s films are full of inception situations—the moments when these sketchy and/or fabulous personae come into being. “He is coming awake,” as the wild child’s caretakers say when their instruction begins to take hold; “You started from scratch,” as Lena narrates the story of Edouard becoming Charlie in Shoot the Piano Player.

There are two narrative forms the subsequent histories of these “just born” characters can take. One is through a kind of anthropology, most academically exact in the way Dr. Itard (Truffaut) in The Wild Child overcomes his doubt about plucking a subject from nature, from his own world, and remaking him: “I had elevated the savage man to the stature of moral being.” But it’s there too in the mock-gangster tale of Shoot the Piano Player, when Charlie ponders how he emerged from the same pool as his three brothers, a family of “savages,” of petty criminals. “Now you’re like us,” says Chico when they force him back to the family farm, and Charlie remembers, with forlorn poetry, his first departure, when he was taken away (plucked from nature) as a musical prodigy and his brothers threw stones at the car. “It was like you speaking. You were saying I couldn’t go.”

The other form, not surprisingly, is the fairy tale. “Once upon a time,” begins Lena, recalling Charlie to his previous self; and in Fahrenheit 451, Montag (Oskar Werner) is asked whether it’s true that “a long time ago” firemen used to put out fires, not start them. Fahrenheit 451 may be Truffaut’s truest fairy tale, a suppositional world rather than science fiction, a dream of shiny red fire engines gliding through a green and pleasant land. The repressive society of the future is barely described: the gray concrete of the firehouse; some scrubby countryside around a monorail. Inside this fragile shell, Montag comes to life: “I am born” are the first words to appear on screen, the first chapter of Dickens’s David Copperfield. The lack of interior life here becomes part of the poetry of movement and design (Hitchcockian patterns of subjective and objective tracking shots), the numbed “what if” world the film proposes. Book-burning is not really the subject, it’s more like the MacGuffin.

Mississippi Mermaid

3. “THE ELDERLY ANGEL, HEURTEBISE, WOULD WHISPER THE PASSWORDS”

And these fairy tales of coming-to-life must inevitably entail its end. Truffaut said (in a foreword to André Bazin’s book on Welles) that Welles made two kinds of films, those in which there was snow and those in which there were gunshots. The snow conjures a sadder, grander kind of fatality, and a little of that touches the death of Lena, gunned down in the snow near the end of Shoot the Piano Player. Elsewhere, the sketchy and the fabulous play a part in these endings: Louis Mahé (Jean-Paul Belmondo) in Mississippi Mermaid “reads” his own murder in a Snow White comic strip, then heads off into the snow with Julie/Marion (Catherine Deneuve), his lethal bifurcated lover; the “book people” in Fahrenheit 451 are objectifying themselves as the snow falls. Conversely, few endings are more shocking—“I run to death, and death meets me as fast”—than the gunshot slaying of The Soft Skin.

People make this run throughout Truffaut. Thérèse (Nicole Berger), wife of Edouard/Charlie in Shoot the Piano Player, confronts him with how she prostituted herself for his career, then—“You can’t stop the night. It’s dark, and getting darker”—leaps from a window. Julie Kohler (Jeanne Moreau) is stopped from doing the same at the start of The Bride Wore Black (68), then sets off on a killing spree. Most fabulous is Louis Mahé, who abandons his paradisiacal island in search of Julie/Marion, winds up with a fever in the Clinique Heurtebise—named after Cocteau’s Angel of Death in Orphée—and thereafter travels (at speed, of course) in company with his death.

Truffaut’s sepulchral testament and most unforgivingly bleak film is The Green Room (78), whose hero—an obituary writer at a moribund newspaper—has devoted himself to the memory of his dead, keeping a chapel ablaze with a candle for each of them. He is played by Truffaut as a brisk rationalist, such as the director always plays, but one who has given himself up to a death cult. His own candle must be added to seal the harmony that the Dead, apparently, demand.

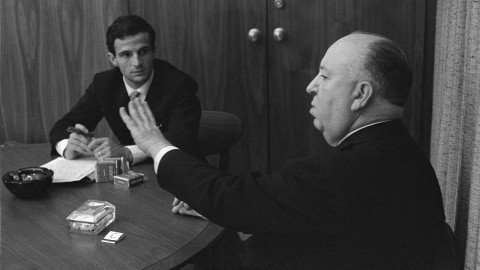

How did Truffaut and Godard fall out, thus shattering the New Wave? Two in the Wave tells how Godard, then in his materialist phase, was driven out of a screening of Day for Night (73) by its romantic take on the movie business: the idea that “movies go along like trains in the night.” An angry, not to say vitriolic, exchange of letters followed. The two never met again, says Two in the Wave—which may be true, but it wasn’t the end of communication. Godard wrote the foreword to the 1988 collection of Truffaut’s letters, in which he evokes “a good time to be alive,” the triumph of The 400 Blows at Cannes in 1959, and Truffaut and Léaud being shepherded along by Cocteau himself (“The elderly angel, Heurtebise, would whisper the passwords . . . Smile at the newspapers, smile at the newscasters!”). Their quarrel was “something stupid. Infantile.” And now, “François is perhaps dead. I am perhaps alive. But then, is there a difference?”