Cracking the Code: Corneliu Porumboiu

The Whistlers follows a police investigator (Vlad Ivanov) who ships out to the Canary Islands and gets embroiled in dirty business—which happens to involve a long-distance language consisting entirely of whistles. I talked with soft-spoken filmmaker Corneliu Porumboiu (Police, Adjective; Infinite Football) in Cannes, where his feature was appearing for the first time in Competition.

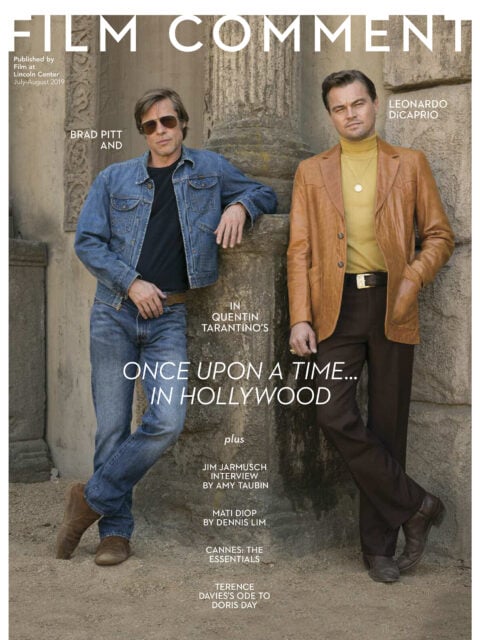

A shorter, edited version of this interview appears in the July-August 2019 issue of Film Comment.

I understand that the idea for The Whistlers came to you from a television show you saw shortly after completing Police, Adjective (2009). What kept you from pursuing the subject for a movie until now, and can you talk about how the film relates to Police, Adjective?

Yes. Right away I was attracted by the language. I tried to read some things about it, and I even wrote a draft of the script, but I didn’t like it, so I did When Evening Falls on Bucharest or Metabolism (2013), I wrote another draft or two, before The Treasure (2015), and I came back to it after that. There were more realistic [versions]—the situation was more like in my previous films. But I had this idea to center on this character from Police, Adjective ten years later—this guy who is very sure about everything in life, but afterward is in a mess.

Was there any thought as you were beginning the project to approach the subject as a nonfiction film? One of the things I like about the movie is that I could see you making a film about this same subject in the style of, say, Infinite Football (2018).

No, it was too powerful and, in a way, too exotic. In fact, the whole time I was hoping that the subject wouldn’t look like just another anecdote from one of my movies. I wanted to make a movie about a guy that is learning this language for a specific reason and it turns against him and becomes a necessity.

What was the process for you as far learning about the language? Did you go to the island and research?

Yes, I spoke with people on the island. They teach the language in schools—they teach it to teachers who are coming to the mainland. So I got in contact with the head of the department of this whistling language in La Gomera, and I observed the classes. But before that I also read a book about the language. There aren’t many studies about it. I found a book on the internet in Spanish, and had someone translate it. It’s about the phonetics of the language, and how you whistle. Now when they teach the language they try to streamline it, and make it more rational. But in fact the whistling can be coded around any Indo-European language.

Did you learn how to do it?

I tried to! We had the teacher come in for two weeks, to give lessons to the actors. But at that same time I was working on the finances for the film. So I had to say, “Ok, I need the money more!” [Laughs] After that I was so lazy. So I know the technique, but I have to practice.

The Whistlers (Corneliu Porumboiu, 2019)

I imagine because of the scale of the production this film was more difficult to finance?

Yes, it was more difficult that the others. I think it was like all my movies combined.

You mean as far as the budget? How much bigger was the budget than normal?

Two-and-half times, I think. Around there. It took some work, mainly because we were shooting abroad.

The scope of the film is definitely larger than anything you’ve previously done. Did you like working at that scale?

It’s another way of working, but at the end of it all, yeah. At some moments we had to find solutions to problems—problems that can’t always be solved with something on set. But as a director I’m used to adapting to situations.

What was the writing process like? After you had the subject and decided to revisit this character from Police, Adjective, how did you go about finding the film’s chapter-based structure?

I wanted to make a movie about a guy who is learning this language for a specific reason, and it turns against him and becomes a necessity. Once I decided to base the script around this character coming to the island, I knew we would need to go back and discover some things about him—like how he ends up there. So, when I added all this up in my mind, I decided to do flashbacks. You want the structure to play upon this process, you know, the learning. I wrote seven or eight drafts [in all]. And even in the editing, I took out about a half hour. I had other scenes that I constructed in the editing room.

So the script must have been quite a bit longer than what we’re seeing in the finished film?

Yes, I took out many scenes—maybe six. There was some comic dialogue and some more comic scenes. They were good—very elaborate. But at the same time, if I used them, I lose some tension.

The dialogue feels very tightly scripted. How was it working with the actors on such precise wording and comedic scenarios?

I think I did a lot of casting through the dialogue, which took a long time. I think a year and a half, character by character. I had Vlad, but I auditioned maybe ten Gilda’s [Catrinel Marlon], for example. It was that type of casting process. What’s in film is quite scripted, because we didn’t have a lot of time for improvisation, like in some of my other films, where you have a lot of dialogue written but you could allow for, say, two or three more lines. This film is meant to be very precise and sharp. But at the same time there were instances on the set when I’d say, “Ok, bring me this scene how it was in the third version [of the script].” So sometimes there were maybe one or two more lines than what was written in the final script, things we brought back.

So some of the actors had read multiple versions of the script?

I think just Vlad. Actually, it was Vlad and Catrinel and Sabin [Tambrea]. Because it was such a long casting process, I was able to speak a lot with Vlad about his part, about his reactions. So the story was built step-by-step. We didn’t talk about superficial aspects of the character, or even about little biographical things about the other characters. We just played the situation.

This is your first full-blown genre film. What’s been your relationship with genre cinema, growing up with it, and what drew you back to it now?

It’s really interesting because I saw noir films in the ’90s, on TV, and after that, I saw them when I was in school. And now when I decided to do this, I said, “These characters [in my film], they’re always role playing, double-crossing… I will watch them again…” I watched The Big Sleep (1946), Double Indemnity (1944), The Maltese Falcon (1941), all the noirs, Notorious (1946). I took a lot of pleasure in that. There was something very childish about it, like when you play with toys when you are a kid. And I said, OK, the next step is they have to play roles, and at the same time, to get this distance—to do it through mise-en-scene, not to be realistic.

The Whistlers (Corneliu Porumboiu, 2019)

What was it like shooting your first real action scenes? Did you run into any technical or logistical problems as you were shooting these sequences?

We prepared very well. The only sequence I was afraid of was the kind of western shootout scene—mainly because of the sound, which I wanted to be more like it was done in old westerns, where hear the gun shots, not the impact. You don’t even see blood. I didn’t want to do it like a contemporary film. And by highlighting the construction of the scene in this way, I wanted to make that moment when then action moves indoors to be a surprise. So that was hard scene to balance. We shot it over three days. I felt like I could barely come up for air. So yeah, maybe that scene made me a little afraid.

Did you go back and look at certain movies for ideas for this sequence?

I watched some shootout scenes from some ’70s films. And I also re-watched The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) and No Country For Old Men (2007). I watched a few neo-noirs and westerns. But that scene was tough because there were many technical things where you have to take care of the actors while making it look real. [Gestures toward his chest.]

You mean with squibs?

Right, with the squibs.

Did shooting in multiple countries pose similar problems?

Well, the first problem was the language, and the island. I scouted the island for good locations. I spent a lot of time there. The sequences on the island are supposed to have a touristic touch in the beginning—it’s beautiful, like a paradise, but after that it begins to develop and reveal different things, you know? And for the garden, I was looking for something to contrast with Cristi’s mother, who tends to her garden.

You’re talking about the final sequence, right, at the Gardens by the Bay in Singapore?

Yeah, in Singapore. I happened to this find this strange, futuristic paradise. [Laughs]

So that location came to you while writing, or were you always planning to use it?

No, I think it was while I was writing the script. I wanted a certain image—something distinct, something new or modern, maybe something from Shanghai.

But you knew wanted some kind of modern architecture?

Yes, but with gardens as well. A garden was important for me. The one we found in Singapore is exactly what I was looking for.

You credit Arantxa Porumboiu as artistic director on the film. Can you tell us a little about her?

Yes! My wife. She’s a painter, and we also worked together on The Treasure. She coordinates the costumes and the set design. Artistic director is a certain type of position that coordinates the costumes and the scenography—the set design. She started a scenography and costumes school in Strasburg. So she’s very good in those areas. She came up with this idea, inspired by all the different color lights in the garden, that each chapter would mark a character in another color, because at the end of the day it’s a journey of the main character. She helped me a lot with the DP, coming up with types of contrasts and helping with this type of coordination. With the dresses, too. Anyway, Arantxa is much better in image culture than me.

So she’s on set with you, then?

Yes, yes. On The Treasure, too. I think it’s more in France where they have this type of concept, the artistic director. It’s someone that is really talking with the director about the film from its conception. [Alain] Guiraudie, I know he works like this. In the American system I guess it’s more like a producer, or production designer. But with me and her, we’re talking every day, and she has a good handle on the scenes. Sometimes she’ll make a comment and I’ll be like, “What, I did that, oh no!” [Laughs]

Is this film a new way forward for you? With Metabolism, you poked fun at your own style, and other Romanian filmmakers, and this is not in that style at all.

I don’t know, because this [style] comes with the subject. Maybe I’ll make a musical! I wanted to make one for a long time, after Police, Adjective, but I never got there. Next time!

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles.