Corridors of Powerlessness

In Bowling for Columbine, there is spectral footage, recorded on a surveillance camera, of the massacre in progress, the chaos of kids running for cover, smoke, confusion. It’s accompanied by a plaintive guitar score—“the sad waste of neglected youth lost in the haze of our rapacious gun culture” is the cliché behind that particular piece of Moore’s overcrowded mosaic. Eventually, even the cliché gets lost.

Who were Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold? Who were all these kids who, throughout the late Nineties, in suburbs across the country, armed themselves to the teeth and walked into school on missions of destruction? We’ve been told that they were friendless loners, taunted by their classmates, that they were fans of death metal and video games, that they had disturbingly easy access to firearms, that many of them were therapized and medicated, and that some of them, like Harris and Klebold, or like Kip Kinkel, the lonely boy from Oregon, were Shakespeare devotees.

But why did they choose to leave their mark on the world in this particular fashion?

More to the point, how did they come to understand this world as the kind of place on which such a mark should be left? An unsolvable enigma. We’ll never know. All possible explanations or combinations thereof—alienation, the longing for notoriety in an oversaturated media culture, the sterility of suburban life, benign parental neglect—seem instantly paltry and insufficient.

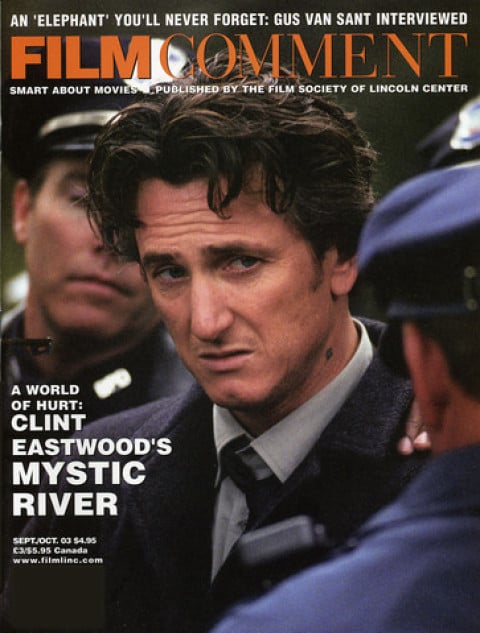

Gus Van Sant knows that the dilemma is unsolvable. And his Elephant is structured around the yearning to know more, to know everything. Nothing comes together in this movie—on purpose. Scenes keep doubling back on the same action, caught from different points of view. Long, breathable stretches of disconnected time are keyed to purely sensual details—a beautiful boy (is there any other kind in Van Sant?) with the blondest blond hair, positioned against the bright bright yellow leaves of a maple tree in autumn; a girl running spastically across a football field in mid-practice and going into some kind of slow-motion ecstasy to the echoes of “Moonlight Sonata”; the odd sensation of following a couple through what seems like the entire length of a high school interior, corridor after corridor. Details are never seized upon, behaviors aren’t tracked or even captured; they’re revealed within the larger unit of unfolding time and space that is the scene. Harris Savides’s camera is in almost constant gliding motion, wandering without apparent purpose or ambition. We’re not so much observing the students as hovering in their midst, and the unfurling action starts to feel like a brilliantly colored flag whipping in the breeze. Van Sant gels a very interesting side effect here. Elephant seems like a study in how much faces don’t give away about people, how much can’t be gleaned from studying them. The film is perfectly built around behavior as the containment of emotions rather than their revelation—in other words, adolescence.

No one has ever done better work with teenagers than Van Sant—put them more at ease, been more respectful of their dilemmas, had a keener understanding of their horizons.

But Elephant is more than just an unobtrusive portrait of youth. The key scene involves that same goofy girl who has the spaz attack on the football field. After gym class, she sits on a locker room bench and changes into her regular clothes. Someone is talking, around the corner, and it’s just barely audible. Right before the scene comes to a halt, the word “loser” floats over the action like a gray cloud.

Here, Beethoven replaces pop music as the soundtrack of teenage life, along with sounds on the threshold of audibility—birdsong, scrambled voices, odd notes, wind, snatches of music. Sounds uttered and whispered, echoing down those long, linoleum-floored corridors under fluorescent lights, banked by picture windows and neutrally colored walls. You walk these uninviting spaces as if your life depended on it, hyperaware of every echo, each one a possible insult and a challenge to your identity.

High school.

And, since the late Nineties, something else has echoed down those corridors. Armageddon, delivered by taciturn boys—always boys—young Travis Bickles fighting to assert their own identities and nothing else. Van Sant and his nonactors make it seem sadly plausible that someone would literally arm himself against the potential ridicule, gossip, and humiliation lurking around every comer.

Van Sant can claim that he wasn’t making a movie about Columbine, but he’s just being cagey. The problem with his movie is that the absences—of motivation, surface emotions, connective tissue—are much more compelling and provocative than the stabs at explanation. The gaggle of girls doing a group bulimic purge in the bathroom may be based on fact, but Van Sant can’t resist shooting it like an expertly timed blackout sketch. More troubling is the behavior of the two boys themselves. The relaxed tone seems utterly wrong, as does the banal conversation on the drive to school, and the instruction from one boy to the other: “Most importantly, have fun, man.” The air of relaxation that informs Van Sant’s presentation often colors his thinking. It’s a bad miscalculation to turn these boys, who take themselves seriously enough to become figures of infamy, into casual killers—their uptight, self-important, world-historical impulse is about a million miles from the innocence of Bonnie and Clyde or the young couple in Badlands.

As usual, Van Sant hedges his bets a little. Right on schedule, the achronological structure gives way to linearity, just in time to turn on the juice for the final massacre—it’s HBO after all. Except … except … for Benny, the beautiful black boy who wanders through the conflagration with an otherworldly calm and self-possession before he’s gunned down, as if he’s seen it all before, way too many times. Benny throws Elephant into a provocative tailspin. HBO got theirs, but in the end, so did Van Sant. Bresson was probably the only director who could have made a great movie about Columbine, but Gus Van Sant, the prince of calculated disaffection, has done justice and then some to the saddest spectacle in recent American history.