Clear as Sunshine

To get something of the measure of the emotional investment that Doris Day was capable of as a screen actress, just look at one particular scene she plays in a Marrakech hotel room in The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956). Her character’s husband, a physician played by James Stewart, is preparing to break the news of their young son’s kidnapping to her, but only after he has administered, without asking her permission, a knockout dose of sedative. It’s a wrenching exchange, with Day first holding out against taking the pills before giving into Stewart’s paternalistic browbeating, then fighting with every ounce of her willpower against sleep once he’s broken the news, before finally sinking into an unquiet unconsciousness. No “Que Será, Será” complacency here—Day’s character is established as having surrendered a promising stage career in order to play housewife in Indianapolis, and so to lose her son is to lose what little she has left of herself. That she later shows at least as much competence as Stewart in accomplishing the boy’s recovery is Hitchcock’s sly joke, a goof on the film’s title.

Day, who died in Carmel Valley, California, in May at age 97, was famous for her beaming, cloudless cheer and bounding energy, but she had also an immense capacity for exasperation, embarrassment, and even, yes, despair. Though she was often discussed as an icon of wide-eyed all-American innocence, a key component of her persona was in fact circumspection, self-preservation. She was only too happy to do low, even cornpone comedy, as she had no mystique of the eternal feminine to uphold, but even when playing a woman named Calamity, she wasn’t reckless, exactly. Her women kept an eye on themselves because they could be hurt terribly, and because furthermore themselves was all they had.

She had been born in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1922 as Doris Mary Kappelhoff, her family part of that city’s then-vast ethnically German middle class. She went to movies with her mother at the RKO Albee downtown, took ballet and tap at Hessler’s Dance Studios where a fellow student was future On the Town (1949) star Vera-Ellen, and aspired to be a dancer, forming a duo with one Jerry Doherty that performed around town. That dream shattered along with her right leg in a 1937 car accident that left her laid up in bed with little to do but sing along to the radio, imitating the clean, nuanced phrasing of Ella Fitzgerald, and to discover her backup plan. At this time Cincinnati was a recording and broadcasting center, home to the country’s only 500,000-watt radio station, the superpower WLW, which broke acts like the Clooney Sisters, the Mills Brothers, and Day. Her regular appearances on the amateur program Carlin’s Carnival brought her to the attention of bandleader Barney Rapp, who began her on a career as a big-band vocalist.

Her first #1, recorded with Les Brown and His Band of Renown, was 1945’s smooth-riding “Sentimental Journey,” and many more followed. The leap into pictures came when she impressed Sammy Cahn and Jule Styne, who’d written the score for a project at Warner Brothers titled Romance on the High Seas (1948), and who convinced her to audition for the role of gum-smacking honky-tonk singer Georgia Garrett for the picture’s director, Michael Curtiz. He was impressed enough to proclaim Day “the most everything dame I have ever seen,” and once she’d signed a Warner contract went on to direct her in My Dream Is Yours (1949), Young Man with a Horn (1950), and I’ll See You in My Dreams (1951). The highlight of Day’s Warner years, which ended with 1954’s Young at Heart opposite Frank Sinatra, is the riotous Calamity Jane (1953), a gender-bending Wild West musical which gives Day free rein to practice her knack for knockabout laffs as the tall-tale-telling frontier scout Martha Jane Canary.

Her best roles came through Hitchcock and in George Abbott and Stanley Donen’s film of the Broadway hit The Pajama Game (1957), in which Day joined most of the original cast, taking over from Janis Paige the spitfire role of union leader “Babe” Williams, her revved-up energy matched to the dynamo pace of the film’s factory-floor setting. The peak of Day’s celebrity came in a series of romantic comedies variously produced by Stanley Shapiro, Ross Hunter, and her husband Martin Melcher, among them the Rock Hudson trilogy of Pillow Talk (1959), Lover Come Back (1961), and Send Me No Flowers (1964). Her box-office dominance was as complete as that of any actress in the history of American pictures, but didn’t live out the ’60s. Day fit not at all into the emerging counterculture youthquake with her sculpted pop-art bob and official air of guarded propriety—official I say, for she was once a touring musician, of whom Oscar Levant quipped, “I knew Doris Day before she was a virgin.” She might’ve pivoted to serve the new, “adult” Hollywood by taking the proffered Mrs. Robinson part in The Graduate (1967), but didn’t budge to the times, and so would be pegged a cultural reactionary. Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro (2016) can be found employing clips of Day to embody white obliviousness, following James Baldwin’s characterization of the actress’s image as one “of the most grotesque appeals to innocence the world has ever seen.”

As so often was the case, it was left to Molly Haskell to redeem this favorite of female viewers, as she did in the pages of 1974’s From Reverence to Rape, noting that the “comic obstacle course of Doris Day’s life, her lack of instinctive knowledge about ‘being a woman,’ and the concomitant drive, ambition, and energy” spoke more to a lived American reality than did the postures projected by many a critical favorite. Haskell’s analysis, and a dossier published in 1980 by the British Film Institute, Move Over Misconceptions: Doris Day Reappraised, helped budge critical consensus, while Day’s popularity among her faithful never really faded, and today she looks less anachronistic than most of her hip critics. If Day’s persona in her comedies doesn’t read as contemporary exactly, it is by no means the punch line it was regarded to be by the late ’60s. She repeatedly plays a deliberately childless, career-obsessed woman past the ingénue age but still cautiously interested in romance, desire vying with wariness over what a commitment could mean to her autonomy—which is to say, a figure familiar to many women today.

If Day’s heroines have seemed unduly anxious about men, Day’s personal life suggests such anxieties about the opposite sex were not unfounded. Her parents separated over her father’s infidelity. Her first husband, trombonist Al Jorden, was a violent schizophrenic, and his abuse sent her running back to Cincinnati. Her second, the saxophonist George Weidler, was jealous of her fame; her fourth, maître d’hôtel Barry Comden, jealous of her pets. Her third, Martin Melcher, burned through her earnings and left her holding the bag when he died in 1968. She balanced the ledgers by fulfilling the television commitments he’d signed her into without her acquiescence—the man who thinks he knows too much, again—playing in saccharine sitcom The Doris Day Show (1968-73) and then settling into the occupation that would be the focus of much of the long life still remaining to her, rescuing and looking after animals. One likes to imagine this a more or less happy ending, like her widow’s life in Frank Tashlin’s The Glass Bottom Boat (1966), with a household menagerie of mynah birds and tropical fish.

This was one of Day’s two films with Tashlin, whose broad-stroke, socko comic sensibility meshes nicely here with her own. She worked once only with Hitchcock and Donen, and this paucity of worthy collaborators is to be lamented. As the greatest female star in Hollywood in a period that was not Hollywood’s greatest—something like the heavyweight reign of Floyd Patterson—there’s still a temptation to asterisk her accomplishment, but even in negligible works she’s a dead-game, leave-it-all-on-the-field comedienne, often offering vocal performances that sometimes suggest depths of feeling and knowledge beyond anything evident in the films themselves. The recording career is still another story, with 1962’s Duets with the André Previn trio exemplifying her enormous talent.

For her final five decades Day was gone but not forgotten. George Michael name-checked her in Wham!’s sugar-high 1984 “Wake Me Up before You Go-Go,” singing “You make the sun shine brighter than Doris Day!”—a tribute from one icon of effervescent pop to another. Day was beloved for her shine, but she was no more naïve in her happiness than was Michael in his “CHOOSE LIFE” T-shirt; it was precisely her gift to make the optimism that marked her characters understood as a choice, one of the many choices with which they negotiated the rocky shoals of a woman’s existence. That this can ring deeper and truer than blasé postures of sophistication is something that Day’s fans have always known, and that new ones will continue to discover.

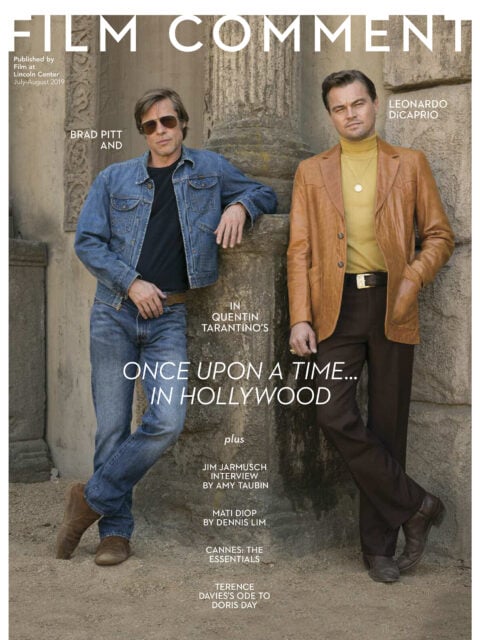

This is a longer version of an article that appeared in the July-August 2019 issue of Film Comment.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.