Interview: Claire Denis

Just as Claire Denis has staked out a position on the fringes of cinema, so her heroes and heroines are outsiders and outcasts, consigned to displacement, marginalization, and exile, be it literal or figurative. This is a cinema of radical estrangement and obliquity, encompassing extremes of lyrical impressionism in Friday Night (01) and stark brutality in Trouble Every Day (01). From Chocolat (88) to I Can't Sleep (94) to Beau travail (99) and beyond, Denis has steered storytelling into increasingly more abstract, dreamlike, and elliptical realms. Hers has been a sustained—and, from this viewer's perspective, extremely rewarding—effort to explore the tensions between the tenuous interior states of her characters and the sensual external world that encloses and often overwhelms them.

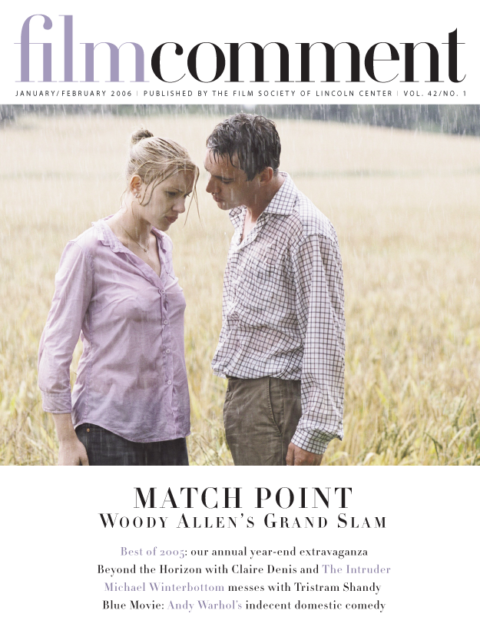

With its cryptic gaps, unpredictable shifts, and daring conjunction of minimal exposition and maximal audiovisual impact, Denis’s latest and most geographically far-flung film, The Intruder (L’Intrus), feels like the culmination of her intuitive aesthetic enterprise. All of her familiar preoccupations are present: the residues of post-colonialism, the imperatives of carnality and the yearning for sensual release, the pervasive sense of temporal suspension. The film’s ostensible narrative is simple enough: a man with a failing heart abandons his reclusive life and estranged son in rural France and arranges for a black-market transplant in Korea; after the operation he travels to Tahiti, attempting to locate another abandoned son and reinvent his life of solitude—until his actions catch up with him, fulfilling the cautionary message contained in the first line in this film of few words: “Your worst enemies are hiding inside, in the shadows hidden in your heart.” It goes without saying that the story is not the main event. The Intruder is far and away Denis’s most enigmatic film, an oneiric narrative filled with baffling, seemingly metaphoric incidents and non sequiturs—visions, encounters, and apparitions that stubbornly refuse to add up, but can only be understood, finally, as the projections of the self-mythologizing protagonist’s own psyche.

The Intruder’s impassive, self-contained main character is played by 70-year-old Michel Subor, rescued from near-obscurity by Denis for his small but indelible role as a Foreign Legion commandant in Beau travail. With his massive, weathered frame and casual, near-reptilian sensuality, Subor is like a Lucian Freud portrait come to life—indeed his commanding yet inscrutable presence is the film’s virtual raison d’être. Denis counters the eroticized topography of Subor’s physique with a poetic progression through a series of similarly eroticized landscapes: the impossibly lush yet brooding forests and hills of the French-Swiss border, the bustling modernity of Pusan in South Korea, the dazzling and humbling ocean expanses and tropical jungles of Tahiti and French Polynesia. The contrast between these dramatically opposed landscapes is simply breathtaking.

Alternately mystifying and deeply moving—and unbelievably vivid from the first frame to the last—The Intruder is cinema at its most wondrously exhilarating.

In your 30s you were an assistant director. What were you doing before that? You were 20 in May 68—what were you up to?

I was already married to a photographer. He worked for Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar in England. I met him when I was 15. He asked me to model for him, and finally we got married. He gave me a Leica and I worked as his assistant. It was a strange situation: he was my husband and he was teaching me things. It was no fun to have a private life together and to also be his apprentice. I was on the side, on my own, doing my own things, meandering, but it was leading me to cinema indirectly. He was very much a cinephile. It was great for me, really. I had not been to the movies very much when I was a kid. I decided to try to enter film school and was selected in 1971.

How many years were you there?

A couple. IDHEC almost closed. After ’68, the school had been taken over by the students. The school’s director was a French filmmaker, Louis Daquin. He was great, maybe not perfect in terms of tuition and organization, but he had a great spirit. He was a member of the Communist party and his films were very political, about things like the coal miners in the north of France. He started making films rather young, but he was well known, well respected, and very militant. And he was sort of blacklisted. He couldn’t find money to make films. He brought in people like [cinematographers] Henri Alekan and Sacha Vierny. Peter Brook would teach us about directing actors. It was very alive.

A few years ago I spotted your name in the credits of Dusan Makavejev’s Sweet Movie. Was that your first job?

First job on the payroll. I had worked as an extra on Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer. You can see me walking by the Seine in a night scene. One of my teachers was Pierre Lhomme. He was the DP and he recruited students to be extras. One day, I don’t know why, someone told Dusan Makavejev that I could speak a little English. He did not want to speak French and he wanted a go-between for him and the crew, a sort of second assistant. He told production that he didn’t want a professional assistant, he wanted someone who knew nothing about the set. I met him and he really liked my total inexperience. I was his assistant on the film but the production also hired a real first assistant, a tough guy who made all the call sheets and stuff, but who had to hide from Dusan.

The Intruder

It must have been a very unconventional production…

After two years in school working with Peter Brook and Louis Daquin, it seemed normal to me, believe it or not. All these dramatic episodes seem completely normal to me. Pierre Lhomme, who was the DP again and who hated Dusan, told me, “This isn’t how things are supposed to go, this is crazy.” I felt fine. Dusan was a little bit afraid of the Otto Mühl community. They refused to stay in a hotel, so they lived on the set, which was built in a garage. Dusan was tempted to sleep there and have a meal with them, but he was afraid, so he had me try it. It was terrifying.

Their performance in the movie is unbelievable.

But it wasn’t only in the film. They staged everything. And because I was their only audience, they did terrible things. They wanted me to shave my head, drink my blood, eat my shit, things like that. But, in a way, I was not afraid. Maybe because I was smoking pot. I was Dusan’s assistant so I had to be there and I took it seriously. Otto Mühl didn’t impress me at all. Some of the cast and crew were impressed. For me it was a great experience. What I liked was the way Dusan put people together who would probably not meet in normal life. It was like a chemical reaction. And he experienced it with great delight. That kind of fear and delight was an interesting way of making films. I never thought we were making an experimental film.

The Seventies was a time for experiences like that, I thought it was completely normal. What seemed strange to me was that people were still making films like nothing had changed. Sixty-eight was such a big change in France, like an electroshock, but it didn’t immediately affect filmmaking. The directors of the Nouvelle Vague were still young. Of course Godard made that move into militant filmmaking, but he had completely disappeared. The others were just making films. No—I’m being unfair to Jacques Rivette. When I was working with Dusan, I told someone that the only person I wanted to work with was Jacques Rivette. A week later, thanks to Louis Daquin, I was taken to the set of Out One. The DP, Pierre-William Glenn, was teaching at IDHEC. When I became a professional assistant, it didn’t seem so real to me, having worked with Jacques, Dusan-and Fernand Deligny, who I assisted on Ce Gamin là (75) a film about a guy who teaches autistic kids. (Deligny was a sort of French Bruno Bettelheim but with different ideas about how to raise children. He made a few films, he is famous in France. Truffaut secretly gave him a little money because he needed his advice for The Wild Child.)

I didn’t see filmmaking as leading me to a professional life-it became a profession for me because I could pay my rent. But it was always in my mind that if I was going to direct a film, it would not be experimental but… Making a film had to be, not a personal experience, but an experience for the crew and the actors, something we would go through together.

As a director, do you see yourself as kind of a misfit?

I fit in my idea of cinema, sometimes there are connections. I know some people like me, and they help me to produce my films or distribute them, but I never ask them what they think about me. But me, I feel unfit. I don’t like to think I am violent and sometimes bad-tempered. I hate my day when I cannot share it with the crew and the actors, and I hate a situation where I am the only one to believe in a scene. I have to convince everyone. When I cannot, I feel very bad.

Are you conscious of making films about outsiders?

But when people ask me why are they about outsiders, I cannot answer the question because it seems like a political attitude. I told you when I was working with Makavejev, I was always ready to be inside, because I never felt inside. Makavejev told me to sleep with Otto Mühl and I wasn’t afraid because I was unreachable, not because I am a pretentious person but because I have a dreamy distance with reality, which is not a really good thing.

Trouble Every Day

I think it’s very good for films.

But for life it is not.

Maybe not. I have always felt that your films were very difficult for me, maybe because I tend to be rational despite being drawn to the poetic or imaginative work. I look at a film and try to understand its mathematics. But that doesn’t work with your film.

As an audience, I do not ask any questions of the film. The film can lead me anywhere. I can go and see any film, a good or a bad one. In Saraband, when the young girl speaks for the first time about her father and there is this flash image of the father grabbing her. It’s a vision, probably not the vision of the girl, but it blew me away. I say this is the greatest thing I have seen this year. A real vision, a vision of violence, but something that doesn’t tell the exact truth, because it’s kind of hard to speak about the relations you have with your father. It feels like a kind of hidden consciousness. I am not able to do that. But I understand logic. I have been educated to be logical, so I know what logic is.

But you don’t choose it?

No, but I don’t reject it as something I don’t like. I’m the opposite: if I have a discussion with someone, I would not be very tolerant with someone who has no logic.

But when you watch a film?

I ask for nothing.

Do you feel torn between the need to tell a story and the desire to go for something more abstract? It seems anything you can do on a visual level to make the film abstract like a painting, you do.

But I do it in a very honest gesture. I think when the location is right for the story in a very logical way, it’s easy to film. If the location is beautiful but wrong, it doesn’t work. It is very painful to choose a location because it seems good-looking during pre-production then to realize it’s only good-looking. It is completely unfair to the story. Djibouti is very beautiful, but I would have never used Djibouti if it were not a territory chosen by the real Foreign Legion. It is very hot, very dry, and very spiritual place to train their guys. And I told the crew that the beauty is not the purpose for the film. You really have to forget this beauty. The work is elsewhere. When I shoot or choose a frame with Agnès, it’s never aesthetic, it’s always logical.

There is a very unusual shot in Beau travail, which must have been done with a very long lens, where you have the soldiers digging in the foreground and in the middle distance is the sea and then on the horizon there is sky and it’s all one plane. It’s like a Rothko painting.

The sound of the digging is mute because the wind blows it away. But it’s not a long lens. It’s a 50mm, but the heat and the dust makes a lot of smoke. The cliff and sea are in the distance, but with heat waves that kill the perspective.

That’s an example of what I meant about abstraction overwhelming narrative.

Well, I have to tell you, I could have made that shot last 30 minutes. For me it is the most comical shot in the movie. You see that landscape, those stones that are lava from the volcano. It’s 50 degrees [Celsius] and those 15 guys are digging solid rock. I did the film before 9/11, so at that moment I thought the Foreign Legion was of no use anymore. For me it was like Beckett. No, really. It had absolutely no aesthetic purpose. Of course when I got to the editing room, only then did I realize all the variations of blue and the mist, the waves, the heat waves, and the dust. It was staged almost.

Is abstraction in your films a device for getting us inside somebody’s head? I’m thinking of the traffic jam and driving scenes in Friday Night—it all becomes a kind of a blur and it’s there to keep us inside [Laure’s] mind.

It’s like a warning signal for her: maybe this guy is wrong for me.

And perhaps from the moment she falls asleep in the car, nothing we see really takes place. It’s all a fantasy or a dream.

Maybe, yes.

He gets out of the car, he walks away, she drives around for a while, then she sees him in a café. It’s unbelievable except in terms of dream logic.

I would say there is something, for someone who experienced the strike of ’95—Emmanuèle was inspired by those long strikes—a very strange thing happened. People meeting, falling in love, changing life. So, yes, it is the language of dream. And yet a moment like a strike creates a suspended moment. The reality suddenly changes. There was a subway strike 10 days ago in Paris. It was the end of winter and was suddenly very warm. Paris changed. People were not going to work, they were in cafés. It was something completely non-aggressive. People were smiling. But it only existed because of the strike, no subway, no buses. I was walking home and I felt something different, like something could happen. Emmanuèle was trying to convey that feeling. I play my part in it. I accentuate it even.

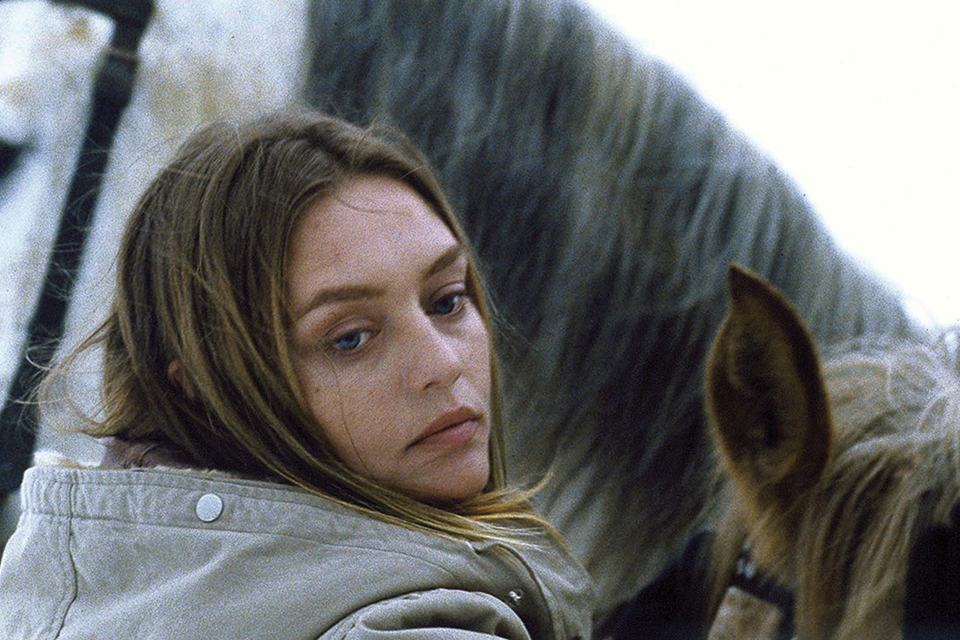

Nenette et Boni

It’s interesting that you bring up suspension because that’s a consistent quality in your films—certainly from Beau travail on. This feeling of being outside time. Where that comes from and is it something you’re conscious of?

I am conscious of it in my real life also. For me a good day is when I dictate time and a bad day is when time dictates me. Days when I have to do something according to time are not very creative and generate a lot of anxiety. But when I can check the time—oh, I still have one hour to do this—it’s always perfect. I think I kind of give that to the characters in the films. They want be free of order. Logic is like a watch. It doesn’t work so much with me. I try to free characters from that. Like the young man in Nénette et Boni works, but the dead of night belongs to him, and when Nénette intrudes on his life, the time becomes different. Because she is pregnant, she has her own time. It completely interrupts his dreamtime.

Why do you begin The Intruder with the main character’s son? Actually, not even his son, but the son’s wife?

[Originally] the first scene in the script was like a monologue of a son who was unemployed, as if he was writing to his father, complaining about his lack of love and his selfishness and pleading with him to be a father. It also explained a little bit about his father’s strange past. We had no time to shoot that scene because Grégoire had to accept another a film and was never able to come back. So it was supposed to begin with the son.

And then shift very radically to be being about the father.

And then the forest. Instead I put in the scene at the border with his wife. And in the original script, it did not end with Beatrice, it ended in the forest—with no people and no snow. As if it was the monologue of the son finishing. As if the whole film was contained in that monologue.

It must have been hard coping after your producer, Humbert Balsan, committed suicide before The Intruder was released in France.

It’d never happened to me that a producer, and a friend, hung himself in his office a month and half before a film is released. I never experienced that before, and I wish I hadn’t. The bank stopped everything. I couldn’t get any more prints made. I had to solve everything. It was an ordeal. But it’s more than that: it’s a pessimistic conclusion to all those years when Humbert surfed on the wave of difficulties. He was so brave, he liked adventure. I knew him from the time when he worked with Bresson [as an actor on Lancelot du Lac], and it was always a running joke—when are we going to work together?