Cinema With a Roof Over its Head

Where are movies at today? One thing's for sure: we’ll never find out from all the critical posturing that’s been going on. The rousing enthusiasm for Todd McCarthy’s Variety blast at this year's Cannes competition was utterly breathtaking. Critics were suddenly coming on like the Red Cross, with an outpouring of concern for the tenderhearted majority. What’s up with all this sudden compassion for the common man?

In fairness to McCarthy, his piece was thoughtful and intelligently written, far more durable than most of the diagnostic / prescriptive “think pieces” that have been appearing with laughable regularity these last five years. The suggestion that world cinema desperately needs (unconsciously wants?) some kind of Hal Wallis figure to keep out-of-control directorial egos in check is absolutely, irredeemably nutty. Is it 1942 again? It’s as if we’re taking our cues from the critic who wondered how Mr. Welles could possibly ask us to care about the Ambersons when our boys were risking their lives overseas.

It seems to me that this particular drum started beating about three years ago with the appearance of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Goodbye South, Goodbye (1996), with which Hou joined the ever-growing number of filmmakers who appear to have climbed too far out on the limb of aestheticism, showing no regard whatever for their paying customers. Not that Hou is lacking for admirers around the world, but in America he seems to have become a marked man before making the transition from cult phenomenon to arthouse favorite.

Goodbye South, Goodbye (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1996)

Why would film critics—any film critic—at the end of the century consider a populist litmus test to be a valid tool of the trade, unless they were trying to pitch woo to their readership? The fact is that it’s easy to imagine a cinema of mass appeal, where the popular and the artistically ambitious merge, if you’re an American and your country’s film industry has dominated the rest of the world since before the dawn of sound. Being a non-American filmmaker is tough, since American culture in general and American movies in particular set the standards for so much: technology, philosophical outlook, narrative construction, modes of production, and, most importantly, the question of how a film should relate to its audience. Compared with a straightforward, visceral, traumatic history lesson like Saving Private Ryan, almost anything is going to look minoritarian and elitist. God forbid if your country’s history is as messy and complicated as that of Taiwan, where national identity is a permanent question mark. Trying to conjure up a form that will accommodate such fragmentation, and stay true to the odd sensation of losing what there is of your culture to mercenary capitalism, is a tall order. So even if Hou were some effete aesthete, he would deserve a little extra credit for just trying. But at a time when the film image is in real danger of succumbing to the digital image, painting Hou Hsiao-hsien as some rare bird who caters to festival directors seems suicidally wrongheaded, a little like turning away a drink of water in the desert because you don’t like the tint of the glass.

Among Hou’s trio of late “difficult” films, the one to garner the least respect is Goodbye South, Goodbye. But is there another film since Warhol with a better sense of just hanging out? It’s about how time feels as it’s passing, about the feeling of simply existing, moving through life as most people do, no big deal, caught in a state of being itchy, nervously under the gun, pressured from outside to perform, to straighten up, to make a little money. “My theory was that the readers just thought they cared about nothing but the action,” wrote Raymond Chandler. The conflict between the narrative and the nonnarrative is an old story. But in Hou’s films, the later ones in particular, the balance between the sense of a story being told and a continuum of life imparted to the camera is not just a happy coincidence—it’s precisely what Hou seeks. Every space is allowed to live as itself, and the size of the people in relation to what’s around them always sits on the border between observation and involvement, between respect and interest.

The hotel room lair of Gao, Flatty, and Pretzel in Goodbye South gets a limited number of compositions that accentuate the boxlike shape of the room. Three almost-losers, spending time together in a cramped room, out of it, their boredom itself a numbing opiate. The miscellaneous activity—tossing a ball, angrily tuning out everything else in the room and concentrating on a video game from floor level, trying to talk on the phone and sleep at the same time, a blowup that ends with Flatty disappearing out the window, Pretzel sitting on the toilet and not bothering to close the door—is perfect, stretched to just the right length. And it never boils over into overextended improvisations, or the cute aimlessness of mid-Eighties American independent films. Hou’s scenes are never “studies” in mood, and they never get into the kind of poetically tinged sociology that is the standard in third-tier French realism. There’s always a balance; every scene is specific, exacting, hitting the right story points. (Here it’s the impossibility of Gao’s situation, his running out of steam after too much scamming and hustling, Flatty and Pretzel’s relative ineptitude, the strange mix of intimacy and annoyance that colors their nomadic, unmoored life together.) But as those points are being made, a space and a mode of being register on our senses through depth, color, hypnotically repeated motion.

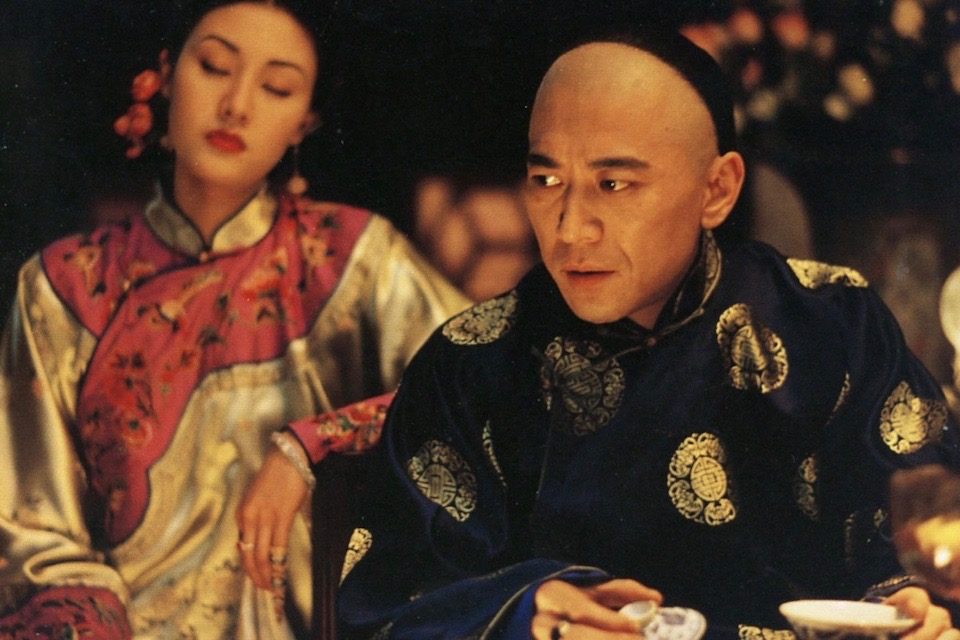

Flowers Of Shanghai (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1998)

Almost every shot Hou has ever filmed has a ravishing arrangement of light and shapes, little corners and crooks of color or darkness that the eye tunnels into, half-defined spaces. In his three latest films the concentration induces a form of delirium. In Good Men, Good Women (1995), Annie Shizuka Inoh sits in front of a mirror and puts on makeup as Jack Kao caresses and fondles her from behind, and throughout the space little semi-disclosed passageways and pools of light surround the tilted mirror, suggesting an array of passage ways into new dimensions, like the hole in the wall that led to the fourth dimension in the “Little Girl Lost” episode of “The Twilight Zone.” Almost any given space in Flowers of Shanghai (1998)—the dinners, the visits to the chambers of the various flower girls—is multi-planed, jewel-like, bewitching. The ancient Chinese aesthetic concept of liu-pai—allowing what’s visible within the frame to open out in the mind of the viewer onto the world that extends beyond its parameters—is expanded in the new films, where space at times feels as if it could spring into any direction.

Characters in Hou operate within strictly defined behavioral limits. Jack Kao’s Gao in Goodbye South, Goodbye is a leathery but amiable guy in a buzz cut, sunglasses, and loud shirts, with a nice disposition and a friendly, slouching posture, who’s watching himself lose control of his own life. Tony Leung’s Master Wang in Flowers of Shanghai is prone to melancholy and a delicately formal social manner: wanting to walk away from all the drinking games, the opium pipes, and the beautiful flower girls and spend his life thinking about the world but not looking at it, his head continually cocked to the side in a semi-smile. In Hou’s work, the question that obsesses the mind of every Western filmmaker—“What makes my characters tick?!?”—has been settled, and the sense of mystery lies elsewhere. These three movies are studded with piercing moments in which characters worn down to a permanently ruminative state are quietly overcome with the question of how they have arrived at their own particular fate, how they have come to be in this particular place at this particular time under this particular set of circumstances: Gao’s little reverie with his girlfriend, or his crying episode in the southern hotel over what a fucked-up disappointment he is; the utterly flat, desolate tone of Annie Shizuka Inoh’s crawls to her fax machine to get more pages from her diary in Good Men, Good Women; Leung’s quiet withdrawal from social interaction during the first, stunning dinner scene in Flowers.

Flowers of Shanghai (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1998)

Each of these movies is an adventure in form, and in tone, too. Goodbye South, Goodbye moves dreamily through time—and “move” is the operative word. Hou was reportedly trying to figure out a valid way to deal with contemporary life (this was his first film with a completely contemporary setting since Daughter of the Nile), and he settled on movement as the central motif. Gao, Flatty, and Pretzel are at peace only when they’re going from one place to another on trains, in cars, on mopeds, from one reverie of failure and regret to the next, from one pipe dream or bad situation to the next, everything devolving to Flatty’s offending the local gangster chieftains down south by coming to claim his share of family money from his corrupt cousin on the police force. The hard facts of the world, where everything is pressurized by time, dissolve into the floating dream of motion. Hou cuts to these flights suddenly, throughout the film, and gets a very graceful, loping form, like a wordless cowboy ballad on the subject of bad luck. The trip up into the mountains on mopeds is lush, cool, muted, an idyll. And then there’s another flight that goes skyward. Flatty (played by Lim Giong, who composed the score, and a very nice performance: lanky, in shapeless bellbottoms, he’s like a giant Ed Norton without the jokes) squats on the roof slowly eating his lunch, looking down as a passenger train stops to pick up passengers and then pulls away. And then Hou cuts with a dreamy logic to the train’s viewpoint as it chugs up into the mountains, where it gets greener and greener. And there are nice little trips down flat rural highways and city thoroughfares, sometimes filtered through the yellow tint of Flatty’s mod shades.

The density of Hou’s concentration within any given shot is apparently infinite, and there’s no such thing as an “insert” or a “cutaway” in his work. Which is why a jump in time or a sudden juxtaposition can feel immense. Starting with The Puppetmaster (1993), the logic of each film is built around the effects of these breaks and juxtapositions. In interviews, Hou often portrays himself as a chronicler, devoted to preserving the bits and pieces of his culture that are disappearing. True enough, and in a sense it’s possible to look at Good Men, Good Women as the contrast between a heroic past and an empty, sterile present, at Goodbye South, Goodbye as a tour through down-and-out modern Taiwan, and at Flowers of Shanghai as an evocation of a disreputable but breathtaking world gone by. But as I said before, Hou is not a documentarian. Once I told a friend of mine that I was reading Proust, and he just looked at me, lifted his arms in the air, and joined them over his head, as if making the sign of a house: art with a roof over its head. In most of the art we encounter, a lot of things are taken for granted: societal and cultural norms and conventions, ingrained ideas, temporary or otherwise. In Hou, as in Proust, nothing is taken for granted, and you get the whole architecture of the world in which the characters live.

The Puppetmaster (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1993)

This occurs most spectacularly in Flowers of Shanghai, which is so damned cool in its balance between individuals and the network in which they operate, between particular actions and their general context, between the ravishing beauty of what we’re watching and the utterly transitory, finite nature of it all. And the repetitions—of dinners eaten over drinking games initiated by overexcited brothel customers (“It’s going to be a great night—order some more dishes!”), of pining men hopelessly confused between love and money, addiction and obligation, of jealous courtesans giving their youthful competition a good talking-to—are in place to give you the motoring design for an entire world. By the time you get to the end of the film, the smell of that world, its texture, its pushing/pulling emotional extremes, its map of power (the men move to the outskirts of the room while the women tend to hold the center) and the precise placement of every character within it, are all so clear and present that the net effect, as in Proust, is of a luxury hotel being taken off its foundations and moved across town.

“It’s something new in cinema,” said the friend with whom I saw Flowers of Shanghai. And he’s right: there aren’t many other films outside of Dreyer’s where every move, every gesture, and every shift in perspective registers so completely. I like Kathleen Murphy’s comparison with Henry James in these pages a few issues back. Unlike Dreyer’s emptied-out images, the images of Flowers have a Jamesian feeling for the world of objects, the importance they hold for characters: as in James, it’s not so much a question of value placed on fine objects as much as a fantasy of devotion that’s projected into them.

I’ve heard that Flowers of Shanghai is difficult to follow, that there are too many characters to keep track of. In fact, what there is of the story is very simple. Most of it’s centered around Master Wang and his addiction/devotion to the idea of love, oscillating between two women, and aging courtesan Crimson and her insistence on fairness. More precisely, it’s also centered around the way that money, the thing that truly brings them together and the subject of which only comes up as a defensive tactic, becomes a bit like the phantom hovering in the room whose presence everyone feels but can’t quite describe. Everything else that happens—the intrigues between the other flower girls (which suggest warring star actresses at MGM in the Thirties), the constant bargaining, upbraiding, and counseling of Crimson’s servant, the aborted suicide pact between the young flower girl and her equally young sponsor who has pledged his undying love to a prostitute—is a deepening, a broadening and restatement of the behaviors, customs, manners, and overall worldview that informs every square inch of the narrative. We never get beyond these lushly appointed rooms (it’s Hou’s one and only studio-bound film), but we don’t need to—this might be the ultimate example of liu-pai. As in “The Beast in the Jungle” or “The Jolly Corner,” the sense of an entire culture is bound up in the precise description of its material world.

Good Men, Good Women (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1995)

Hou’s characters don’t evolve much by Western standards, but our sense of them deepens as the structure of their universe comes into ever sharper focus through the duration of the film. Perhaps the ultimate example of this form of vertical character development occurs in Good Men, Good Women, where you hardly see the actress/heroine in the film’s present-tense sequences—she’s usually crawling out from under the sheets to get another faxed page from her stolen diary. The film, which could be profitably described as Hou’s Providence, operates in three tenses: the heroine’s present, her disreputable past as a barmaid in a disco with a smalltime gangster lover (Jack Kao again, one of the finest presences in modern movies), and a conditional tense of a film about the Taiwanese dissident Chiang Bi-Yu and her husband Chung Hao-Tung, who were persecuted during the White Terror of the 1950s. These scenes, shot in black and white, are from a movie (called Good Men, Good Women) in which she’s about to play the lead, as she imagines it will be.

This may seem like way too intellectual a construct, and it must be said that Good Men, Good Women lacks the immediacy of the other two films. But tones of the various scenes are so carefully negotiated and modulated that it becomes a fairly breathtaking experience. As opposed to Flowers of Shanghai’s ever-deepening perspective from the inside, this film moves from one hallucinatory immersion in visually articulated space to another. And the connections between the different temporal milieux are exceedingly delicate. Inoh and Kao have a conversation about her getting pregnant and getting an abortion, and Hou cuts to Chiang Bi-Yu, pregnant, working in a relief camp. The transition is very movingly rendered: as always with Hou, nothing fancy or emphatic, the idea being to let the connection ease into the viewer’s consciousness. The net effect is of time, experienced from an ordinary perspective, flowing through the medium of a saddened spirit. When Inoh finally confesses to her mysterious faxer that she has not only set up Ah-wei for blood money but also that she truly loved him, Hou cuts back to Chiang Bi-yu preparing her husband’s body for burial after he’s died in the custody of Kuomintang officials. And then he achieves a remarkable effect by fading the color into the black-and-white image. It’s not just a woman’s self-actualization through confession, but the realization that the personal past and the historical past are inseparable, one in the same.

The fact is that no matter how deep an affinity Westerners develop for Eastern culture, the moment always arrives when the conceptually unfamiliar impedes the flow of pleasure, and the bridge to “universal meaning” must be crossed with intellectual effort. Sometimes the day of reckoning can be put off; sometimes, as with the Japanese masters we all revere, some fancy footwork can be done, with Western ideas and paradigms plugging in our gaps in knowledge. But does that instantly invalidate the experience? We expect a sort of generic variety of “Eastern calm” from modern Asian filmmakers, which seems patently absurd, given the convulsive state of that part of the world right now. Unfortunately for Hou, assuming that he actually cares a whole lot about what Westerners think, his early films seemed to fill the bill and his later ones do not. Hou may require a bit of brainwork from the viewer, but does that make him an ivory-tower dweller? Isn’t there room in cinema for the “semi-popular” artist, to use a term coined by the rock critic Bob Christgau? Prompting an artist of this magnitude to make his work more accessible is like asking Stockhausen to write catchier tunes, or asking John Ashbery to appeal to readers of USA Today. It doesn’t make any sense.

Because right now, it doesn’t get much better than Hou Hsiao-hsien.