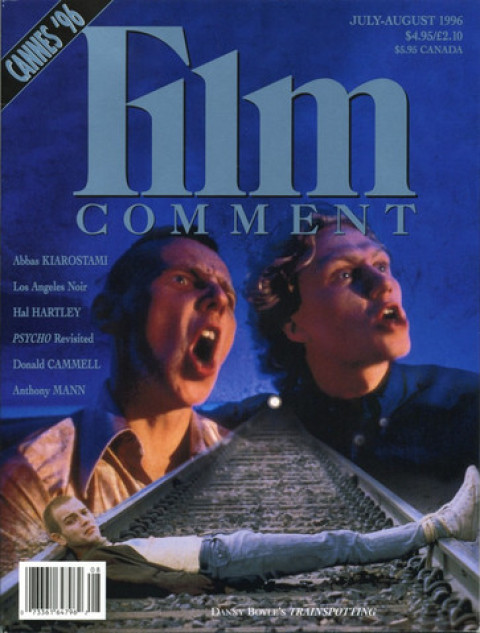

Cinema Sex Magick

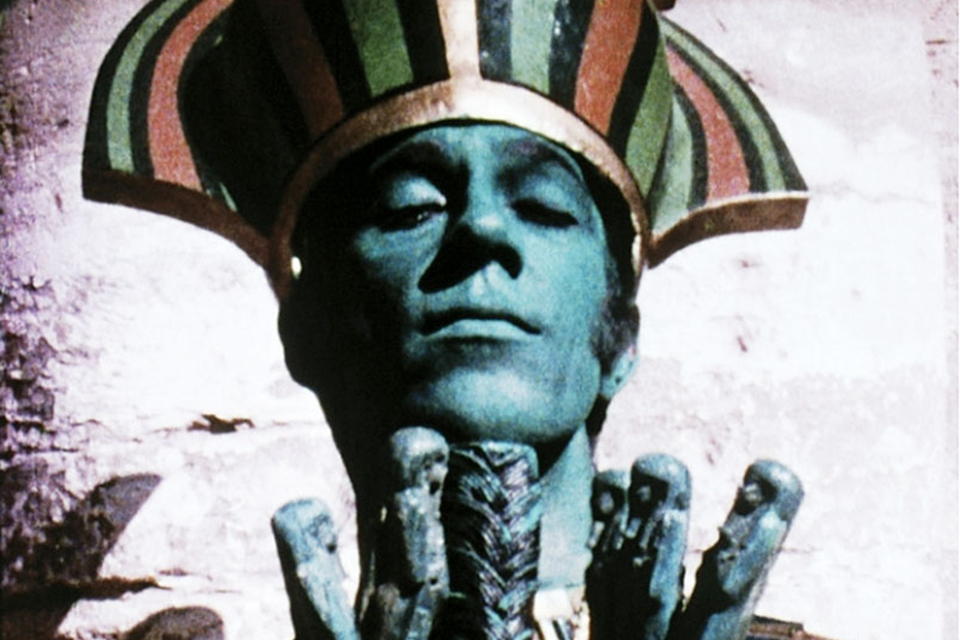

A primordial landscape burns. A molten river carves its way through a terrain in a ritual older than the words that try to name it. Isis, the holy throne-woman, raises her scepter high, an invocation to her partner Osiris (he who sits upon the throne). He raises his in reply. When their eyes connect, sparks fly, the earth trembles, and a reptile crawls forth from its egg. (You are watching a Kenneth Anger film.) In the beginning, Osiris was the Egyptian god of agriculture, but as his story spread he became God of the Dead. His body, you see, was ripped into 14 pieces by a truly demon brother (Setekh); but the loving hands of Isis reassembled him and he chose to stay on as Lord of the Underworld. When the plants along the Nile appear each spring, it is Osiris, reborn.

When Anger began shooting his second version of Lucifer Rising sometime around 1970 (the original 1966 footage had been stolen), Donald Cammell’s Performance had just been released. At the time, Anger and Cammell were exploring similar themes. Both were fascinated by the allure of iconic fame and performance. Mick Jagger had appeared briefly in and composed the score for Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother (69), and his rock-star aura propelled Cammell’s film into the underground pantheon. (It is no surprise that Anger wanted Jagger to be his Lucifer.) In an increasingly relevant turn of poetic inspiration, Anger cast Cammell as his Osiris.

On April 24, 1996, Donald Cammell committed suicide in his Hollywood home. He was 62 years old. His career as director leaves us with only four feature films, a handful of work from a career fraught with frustrations. Adding to the dismay, his first film—and easily his best—continues to be primarily thought of as a Nicolas Roeg film, Roeg having been Cammell’s co-directing cameraman. The irony cuts deep: the male leads, Mick Jagger and James Fox, exchange and merge their narrative identities until the audience is forced into a confused double take. (In the real world, Cammell and Roeg would never publicly discuss who was responsible for what. As the copy for Performance’s posters put it: “Vice. And Versa.”) Indeed, correlations between the two directors’ subsequent careers (Roeg’s being far more prolific) continue to resonate.

Donald Seton Cammell was born in Scotland and in the wink of an eye was a child prodigy. Evidently, he was in the right household for it. His father, the writer and poet Charles Richard Cammell, was the author of numerous books including Faeryland, Verses for the Centenary of Lord Byron, and Aleister Crowley: The Man: The Mage: The Poet. (It has been rumored that Cammell is Crowley’s “godson,” a technical impossibility that will nonetheless be excellent résumé material for Kenneth Anger gigs.) Showing a natural aptitude for paint, Cammell attended the Royal College of Art and went on to become a “Student of Annigoni” in Florence. Father Cammell had also written Memoirs of Annigoni, from which we glean small tidbits of director Cammell’s formative days: The parties in the Annigoni household were intoxicated revels that occasionally involved disguise, role-play, and the absolute adoration of The Beautiful (especially women). Not to mention poetry readings. Staring at a portrait of a lady friend who was possibly (one can only hope) involved in a triangle of love with young Cammell and a fellow “Student of Annigoni,” father Cammell is inspired to speak of a “symbol of the mystery of women’s beauty and of its eternal power over the destinies of men.” He was also fond of quoting Wordsworth: “The child is father of the man.”

Lucifer Rising

In 1953, Alice Mary Hadfield’s young reader’s version of King Arthur and the Round Table is published with illustrations by Cammell. The images are sheer Camelot: in one, we see Merlin and Vivien emerge from woods encrypted in expressionism. In another, Mordred lunges toward the King as they stand on a landscape of slaughtered bodies. In another, a hypnotic line drawing infused with incantatory graphic waves vibrates before our eyes. Underneath we read the words: “For three nights under the moon the wizards practiced their arts.” In London, after establishing his own studio, Cammell creates “Sheridan, the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava,” described by the London Times as “society portrait of the year.” (His work also adorned a few covers of the British men’s magazine Lilliput.) Needless to say, the art is moving away from the sphere of Annigoni and turning to the techniques and concerns of modernity, e.g., seminars with Francis Bacon at The Colony, a British School watering hole. From a review in Arts Magazine (May-June 1964): “The paintings are spare and stark and closely associated with the earth in its least fecund phases.” He will, of course, fall prey to the “eternal power over the destinies of men,” i.e., actresses and fashion models, and make his move into the cinematic medium.

His view from the inside of Swinging London provides inspiration for Cammell’s first screenplays: The Touchables and Duffy, both released in 1968. (In both cases the degree to which we can ascribe a true Cammell signature can only be guessed at.) The former has evaporated into the realm of the unseen. We know it was co-written with Cammell’s younger brother David; we know it was directed by Robert Freeman, who did the titles for Richard Lester’s Beatles movies; we know the story involves the kidnap of a rock star by four young female fans who then tantalize/torture him for his attention (sort of a Misery gone Mod). We know intuitively that we’re in the right ballpark, but that’s about it.

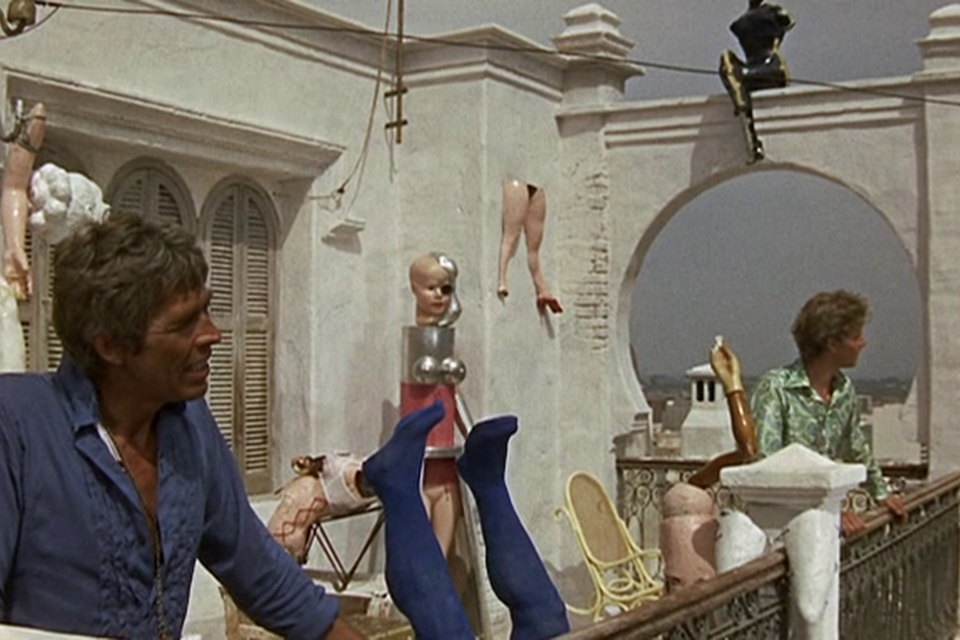

Duffy is a different story. Starring Susannah York, James Mason, James Coburn, and James Fox and directed by Robert Parrish, it tells the tale of two brothers (described by their father as “a nothing and a bad joke”) who concoct a scheme to swindle the old man out of an enormous sum of money. Planning the heist involves a trip to Tangiers (which triggers a “tangerine fields and marmalade skies” aside) and additional dialogue dementia. Coburn: “This whole thing is totally absurd, man!” Fox: “Precisely! You create beautiful absurdities; why can’t I? I want to create a fantastic amateur theatrical! A happening! Sort of like shooting an absurd movie without a camera!” Coburn: “You might have to shoot people, man. That’s not cool.” Give the cast some Mardi Gras attire for their heist at sea and throw in York for polysexuality and there you have it: proto-Cammell. And Duffy’s piracy motif would come back to haunt him; but that’s getting ahead of the story. For the completist, Duffy can actually be found somewhere in broadcast television’s eternal late afternoon. (For the obsessive-compulsive, Cammell can be seen in a 30-second cameo in La Collectioneuse, the fourth of Eric Rohmer’s six “Moral Tales,” made in 1966. Look for him mid-film, standing by his car asking for directions to the sea, clearly visible in the background.)

Duffy

The ferment of 1968 was far greater than the sum of its 366 days. It was, and remains, an endless year. For our purposes, we can bring it back to 1963 and Joseph Losey’s The Servant, an architectonic experiment in role reversal. In it, manservant wimp Hugo (Dirk Bogarde) rises through the ranks of Anglo-aristo degeneracy to dominance. Whose kingdom does he usurp? The inner sanctum of numb-snob Tony (James Fox, in his career-making role). Losey knew, firsthand, what it meant to strike out and colonize new psycho-geographies. He was a relocated American escaping a certain Senator McCarthy back in the homeland. He also had a flair for making films with characters who were practically devoured by their own domiciles. In 1968, Losey made Secret Ceremony, with Elizabeth Taylor as a waning lady of the evening and Mia Farrow as the young, oversexual inhabitant of an art nouveau nightmare. The former is missing a daughter; the latter, a mother. Can you guess what happens? Close, but I forgot to tell you about Robert Mitchum.

The two Losey films set the stage—using the device of fortress-like interior space for identity meld and transfer—for the delirium of Performance. Much has been written on the centrality of this “text” within the Great Books of Decadence. It is not so much a time capsule from the period but, rather, an elixir. To inhale its vapor is to become possessed. The two key elements contributing to its power are the formal psychosis prompted by the camera/editing style and the actual psychosis of everyone involved. Contrary to popular opinion, Cammell cut the film alone. In fact, when Roeg first saw Cammell’s cut, he didn’t like it. Ironically, it would be a few years later in Roeg’s career when he himself would return to the style and then be erroneously associated with its inception. The story traces the trajectory of a feverishly brutal mobster, Chas (James Fox, of course), who has outdone himself and needs to lie low. He seeks sanctuary by conning his way into the ever-unfolding psychedelic interior of reclusive rock superstar Turner (Jagger)’s London house. At Turner’s side are his right-hand sex goddesses (Anita Pallenberg and Michele Breton). With a play of hypnotic music, schizoid montage, and chemical liberation, the four parties are set free to pair, triangulate, and quadranglize. The geometries extend beyond the barriers of the film frame as Keith Richards, Brian Jones, and Cammell himself jockey for libidinal positions in the wings. (Perhaps it truly was Roeg who held this thing together.)

The first time you see Performance, it is a shock to the system. It attacks mercilessly with a barrage of jaggedly discontinuous images and information. The standard film device of planting bits of seemingly innocuous information and then bringing them back later for a narrative payoff has been inverted and diffused into fractal psychology: payoffs are exploding at every turn and it is only later—if ever—that we come across the “plants” that lead to them. The veil of randomness parts and reveals obvious order, which, in turn, crumbles once you’ve grasped it.

Secret Ceremony

The centerpiece—in a film that strives for the off center—is what may be the first fully realized rock video ever made. (D.A. Pennebaker and Richard Lester enthusiasts, hear me out.) Chas has been duped into eating a magic mushroom. The interior environment shifts from Turner’s bohemia back into the business office of Chas’s boss, Harry Flowers. Everything is in its proper place except Jagger—replete in the appropriate mob attire and hairdo—who now sits behind the desk. The music starts and the scene follows the actions we witnessed earlier. Meaningless gestures, repeated to music the second time around, suddenly become psycho—choreography movements impregnated with significance by virtue of formal choices of repetition. A previous scene has been turned into a song—like a jazz standard that can be used as a guide to improvise from.

Unlike the song sequences in Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night and the “Subterranean Homesick Blues” sequence in Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back, “Memo to Turner” creates a miniature world, a microcosm adhering clearly to its own internal, albeit hallucinatory, logic. We enter it when the song begins; we leave it in the end. This “film within the film” is not only a prismatic perspective into Performance as a whole, it also reflects a strategy that will be a Cammell trademark: the use of image echoes—recurrent patterns of symbols and psyches. Heightening the impact is Cammell’s direction of actors, a seemingly tightly controlled method that nonetheless achieves high degrees of freedom. And high degrees of danger: James Fox was so psychically disheveled by the process of Performance, he withdrew from acting and joined an evangelical group for most of the ensuing decade.

The only real way into what was going on would be an interrogation of an involved psychotherapist (which is illegal) or a chat with the drug attendant (who, it just so happens, has written a book). Up and Down with the Rolling Stones, by Tony Sanchez (1979), page 113 (Marianne Faithfull is coaching Jagger on his upcoming film role): “Whatever you do, don’t try to play yourself. You’re much too together, too straight, too strong. You’ve got to imagine you’re Brian: poor, freaked-out, deluded, androgynous, druggie Brian. But you also need just a bit of Keith in it: his tough, self-destructive, beautiful lawlessness. You must become a mixture of the way Brian and Keith will be when the Stones are over and they are alone in their fabulous houses with all the money in the world and nothing to spend it on.” Sanchez goes on to reveal some of the “method” in creating Fox’s role: sending him to an actual gangster’s tailor, gym training with thugs, dry-run burglary expeditions, etc. And, lest we forget, the drugs. Page 115: Sanchez is narrating: “I could see the film draining both Jagger and Fox, for they were being forced to question the very roots of their beings. James, particularly, was becoming as dangerously disoriented off screen as he was on. And Jagger, too, seemed to have become Brian; he was beginning to crack up and lose his identity. The two would smoke DMT together in their dressing room so that they could add realism to the drug scenes. But the drug has the hydrogen bomb impact of a twelve-hour acid trip crammed into the space of fifteen minutes and served to only alienate them further from the real world. Recently doctors have discovered that DMT can cause irreparable brain damage.” Sounds like the voice of authority to me.

Performance

For some reason, when Warner Bros. saw the picture, they were horrified. The ensuing two-year battle over artistic integrity was both “a necessary evil and a process which he absolutely delighted in,” says China Kong, wife and long-term collaborator with Cammell. When the film was finally released a certain superstar responded quite positively to it. His name was Marlon Brando. In 1989, indie writer-director Chris Rodley had the chance to talk to Cammell about Brando and their various hellfire collaborations. His article, “Marlon, Madness and Me,” appeared in the premiere issue of a now-defunct British publication, 20/20. It contains a maelstrom of information but, in true Cammellian style, bends chronologies into confusing configurations.

It seems that around the time Cammell begins work on the Julie Christie vehicle Demon Seed, Brando learns that Cammell is romancing the teenage daughter of one of Brando’s “long-term lovers.” As China Cammell puts it “he did not approve. He wanted to deport Donald.” Eventually, sometime after Kong and Cammell’s marriage, Brando will apologize. In any event, Brando was so impressed by Performance, he approached Cammell as a collaborator. His idea was a Twenties period piece called Fan-Tan. Evidently Brando was mulling over the idea of female pirates (remember Susannah York) and was looking for the writer-director who could bring it to life. The process was frustrating, time-consuming, and came to naught—in the cinematic sense. Toward the end, the preproduction scheme had evolved into a book that would be sold to cover the cost of filming and thereby ensure directorial control of the film. Brando would spew ideas; Cammell would write. Problem was, Brando continually refused advance offers from interested publishers. Why? Cammell: “Marlon maintained that he couldn’t read it if he hadn’t written it himself.” A minor problem coming from the mouth of the man who hires you to write a script. Needless to say, before setting sail, Fan-Tan the movie sinks. The book, however, is a different story.

To back-pedal for a moment, there’s Demon Seed (77). Easily the least Cammellian of the four films (despite the de rigueur incessant battles with the studio), it’s still significant in context. Julie Christie plays the wife of a genius, i.e. pretentious, computer scientist who is the father of Proteus—a superpsychedelic-mind machine. The husband goes off on a research excursion, leaving Christie home alone with Proteus. The mechanism quickly announces its intent to spawn and achieve the best of both worlds, i.e., pretentiousness and sensuousness. Christie’s remarkable performance, with its disturbing blend of repulsion/curiosity and its tightly mannered moments of madness, barely holds the farce together. Indeed, the film allocates what seems like well over half its Total Runtime to the act of consummation itself.

Demon Seed

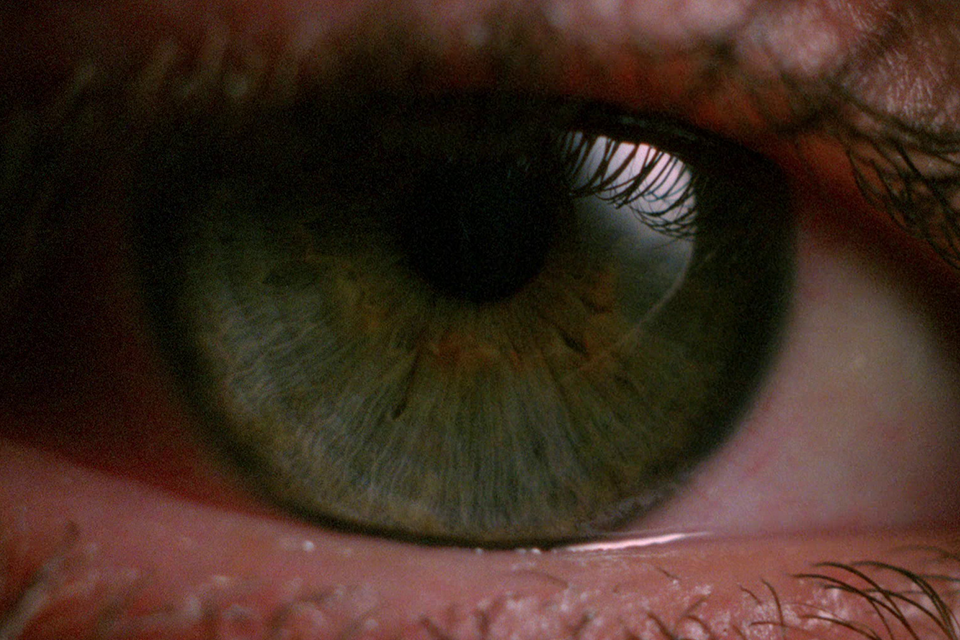

But what an act it is. Basically, you get one part Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother “ZAP/YOU’RE PREGNANT/THAT’S WITCHCRAFT” sequence mixed with one part Keir-Dullea-goes-Beyond-Infinity in Kubrick’s 2001, with Cammell providing his brand of metasexual innuendo. Although the machine is made manifest with an endless variety of elaborate prosthetic gizmos, it is the depiction of its central eye, with all the attendant schizo-montage trimmings, that anchors the image—a voyeur in search of its own body. Cammell collaborator Drew Hammond says, “Cammell planned the film as a comedy.” With the demands of seriousness placed on him by the studio, we’re left with a joke—albeit a funny one. (A few years earlier Christie took part in another indelible sex scene at a somewhat different point in the spectrum as Donald Sutherland’s wife in Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 masterpiece Don’t Look Now. And, in another footnote, the 1978 Brooke Shields flop Tilt credited Cammell as co-writer; he was going to direct, but when the producer substituted Shields for Cammell’s choice of Jodie Foster, he walked. Since Tilt is hard to find, or hard to make yourself try to find, we can only surmise/hope that the “dazzling point-of-view photography inside pinball machines;” according to Leonard Maltin, has traces of Cammell’s Demon Seed machine-eye.)

The Sixties were distilled into Sex and Mysticism for Performance. The Seventies, with Demon Seed, became Sex and Technology. The Eighties, with White of the Eye (87), became Disturbing Sex of Mythic Proportions. Set on the burnt industrial fringes of Tucson, White of the Eye tells the story of a young, desperately passionate couple who become enmeshed in the barbarous web of a serial killer. (Unfortunately for the wife, the husband has quite the collection of nasty trophies hidden in the bathroom.) As the action twists a benign homestead into a domestic nightmare, signature Cammell forms resurface—startling flash-cuts between the recent past and present creating schizoid sensations, an exaggerated emphasis on the eyeball as visual fulcrum for transitional delirium, and a soundtrack that announces invocation and possession. The film is a microcosm of psychological nuance as the seemingly attentive and harmless husband (expertly played by David Keith) slips in and out of dementia so effortlessly that the wife (Cathy Moriarty) and the audience remain suspended in indeterminacy until the very end. She could just take him back. Everything will be all right. We’ll clean up the bathroom and forget about the whole thing. But no, the film ends with a landscape explosion reminiscent of the existentialism of Antonioni. Of course, true to form, the project was riddled with problems—censorship, a bankruptcy proceeding, lack of promotion; box-office oblivion.

In any event, word was circulated and a certain someone Cammell was all too familiar with resurfaced and arranged for a private screening. Marlon Brando had another project he wanted to discuss, and, as described in the Rodley article, it was to be his Swan Song: in Jericho, Billy Harrington (Brando), a retired government assassin, is coerced back into action by evil CIA operatives (they introduce his daughter to a Colombian druglord’s son, who falls for her). Harrington, named after Brando’s psychiatrist who had died recently, embarks on an ultraviolent rescue mission. After “he kills everybody. Everybody! In the last reel,” says Cammell, he returns home to brood in suicidal angst. Cammell: “The overall image of the film is a man living with his own guilt over all the horror he’s perpetrated . . . I felt I knew [Brando] as a performer and I could help orchestrate that performance, to see him bare his soul for once.” The money, even though Brando demanded “a very high percentage of the profits,” was made available. All that was needed was the script that Brando was determined to write alone. And it’s anyone’s guess what that means.

Wild Side

The last film Cammell made, Wild Side, was, upon completion, taken away and recut by the production house, Nu Image. The company is primarily known, if at all, for low-grade exploitation films. According to Drew Hammond—collaborator on Cammell’s yet-to-be-produced last screenplay—”they [Nu Image] were trying to break into the American art film market and achieve some degree of respectability.” A side-by-side comparison of the two cuts reveals Nu Image’s conversion of an over-the-top “art film” into an arty “exploitation film” Everything from the delicacies of humor, the subtle but pivotal implication of Christopher Walken in a homosexual relationship, and the basic and unmistakable Cammellian editing strategy (i.e., the expansion of the film into heightened psychologies) has been removed. The homogeneity of the Nu Image version’s editing style smoothes out all of the danger, all of the power, all of the art. The film was sucked dry and secreted straight to cable.

Bruno (Walken) is a villainous financial racketeer who is manipulating Virginia (Joan Chen), a businesswoman who is also Bruno’s somewhat estranged wife. She meets and falls in love with a female banker, Johanna (Anne Heche). Johanna, in her other guise as a high-priced call girl, is hired by Bruno, who is so impressed by her banking acumen he decides she will become his protégée. Adding the final point to the twisted polygon is Tony (Steven Bauer), Bruno’s chauffeur. He is, of course, an undercover cop. As Virginia and Johanna twist tighter into the bonds of their newfound love and Tony grows more and more paranoid as his sting operation approaches the threshold of exposure, Walken implodes into the kind of performance that appears to damage the actual psyches of the cast, characters, and anyone else who cares to watch.

All four leads are absolutely top-notch and play off the various recombinant possibilities of the narrative with a mesmerizing urgency. The film is a psychosis of triangles within triangles, both love and hate. On the continuum sketched above—Sixties Hex Sex, Seventies Tech Sex, and Eighties Disturbo Sex—Wild Side actually allows for a glimmer of hope at the end of the tunnel, and the Nineties. True love, redemption, and a new life are alluded to. These things are possible in the fleeting conception of escape to the “third world,” an apt metaphor for where things happen—in general—in Cammell’s filmic universe. Be it London, Tucson, or Los Angeles, we are always just a flash-cut away from the point where exotica meets utopia, a place—always dangerous—that can open up and unfold images, characters, or viewers to their own inner-selves.

White of the Eye

Along with four films in four decades and the thwarted projects already mentioned, Cammell produced a steady stream of scripts and treatments whose presence out there in limboland continues to tantalize. Attempting to collate them is like assembling a surrealistic index of possibilities, a soft Rolodex that drips off the edge of the horizon line: Mick Jagger and Norman Mailer in Ishtar, “the ultimate feminist film of all time.” (That combination of names and words is what you call Advertising Copy.) An adaptation of the impossible-to-adapt Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov; the master read the treatment and sent a letter of approval to Cammell. Hammond: “Donald was very proud of that letter.” A collaboration with Kenneth Tynan on the true story of Jack the Ripper, a film that would examine him in light of the Freemasons. An epic historical treatment of Lady Emma Hamilton. A treatment of the life of Machine Gun Kelly. An offer to direct Rob Lowe in Bad Influence. A project called 3000, the amount of money necessary to buy a call girl for the night (and exactly twice the amount that Johanna from Wild Side charged) that was juggled around between studios and eventually ended up as Pretty Woman. And then there’s his last screenplay, ‘33, co-written with Kong and Hammond. In it, a journalist is sent to Istanbul—in 1933—to investigate a heroin kingpin and ends up ensnared in his lair. With Cammell gone, I asked Hammond who would be his wish-list director and he answered, without missing a beat: “Stanley Kubrick.” Not a bad choice, considering that there is an odd parallel between Cammell and Kubrick. Performance has obvious nods to Clockwork Orange, Demon Seed draws on 2001, White of the Eye follows the path of The Shining, and Wild Side is the film Kubrick hasn’t made yet. Kubrick is, of course, the perfect model for the way Cammell wanted to work, i.e., an absolute and unique personal vision stands steadfast amidst the artless tools quivering behind the facades of paranoid studio money.

To end, it is appropriate to return to the voice of Cammell himself. Somewhere within the two-year period between the completion of Performance and its release, Cammell and Jagger fired off a telegram to the president of Warner Bros. It comes to us courtesy of Tony Sanchez (you remember, Keith Richards’s chemo chronologist):

THIS FILM IS ABOUT THE PERVERTED LOVE AFFAIR BETWEEN HOMO SAPIENS AND LADY VIOLENCE. IN COMMON WITH ITS SUBJECT, IT IS NECESSARILY HORRIFYING, PARADOXICAL AND ABSURD. TO MAKE SUCH A FILM MEANS ACCEPTING THAT THE SUBJECT IS LOADED WITH EVERY TABOO IN THE BOOK.

YOU SEEM TO WANT TO EMASCULATE (1) THE MOST SAVAGE AND (2) THE MOST AFFECTIONATE SCENES IN OUR MOVIE. IF PERFORMANCE DOES NOT UPSET AUDIENCES IT IS NOTHING. IF THIS FACT UPSETS YOU, THE ALTERNATIVE IS TO SELL IT FAST AND NO MORE BULLSHIT. YOUR MISGUIDED CENSORSHIP WILL ULTIMATELY DIMINISH SAID AUDIENCES IN QUALITY AND QUANTITY.

Some things never change. Osiris is with us in the springtime.

Thanks to China Kong, Drew Hammond, and Gib from Mystic Fire Video.