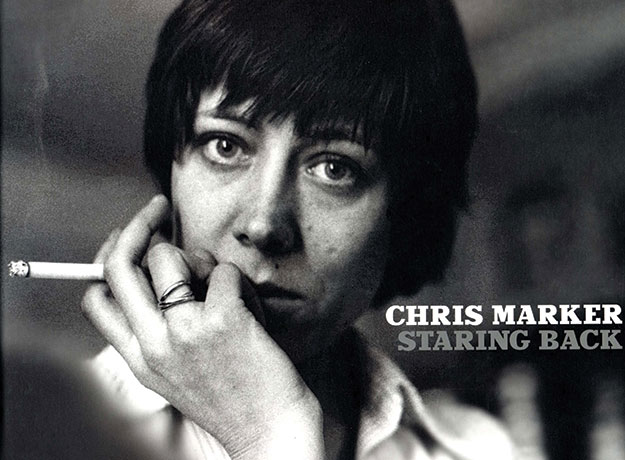

Because Chris Marker is one of the most important filmmakers in the history of cinema (the central figure and innovator of the essay-film genre), and one of the most elusive (refusing to allow himself to be photographed, suppressing showings of his earlier films, given to cryptic poetic statements), any publication that takes us closer to his mind and soul will be welcomed and cherished. Especially by his fans.

In recent years, the octogenarian Marker has been involved in making museum installations, CD-ROMs, and publications drawn from a lifelong archive of images taken around the world. The book Staring Back began as a museum exhibition for the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio. The catalogue for that show, published by the Wexner and distributed by MIT Press, consists of some 200 images and accompanying texts, divided into four sections: 1) shots of left-wing political demonstrations from 1961 to the present, in which the utopian hope of collective action is contrasted with “the everlasting face of solitude” (Marker); 2) portraits, mostly head shots, of people, a few famous, most of them unknown, who stare back at Marker, engage the photographer for a brief moment or two, in dignity (“and me like a fast pickpocket running away with my bounty . . . And now all of ’em are aligned on this wall like they’re waiting for the firing squad or the final Examiner as they will be on Judgment Day . . . ”); 3) fugitive portraits of people whom Marker stared at but who did not make eye contact with him, either because they were rushing past, or their eyes were closed in sleep or death; and 4) portraits of animals, some in the zoo, others running free, who represent for the photographer “the truest of humanity.”

A word of praise for Bill Horrigan, the indefatigable curator who coaxed this cornucopia of images out of Marker, and whose excellent essay tells us as much as we are likely ever to know about the artist’s methods of selection, pairing, and sequencing. He writes: “Punctuating the entirety of Staring Back are images one recalls from Marker’s film, video, and book projects, and from Immemory, here regrouped by their creator for this occasion: an elegant reshuffle of the deck, portraits reclaimed from the printed page, from the trove of moving images, from the ever-morphing digital vault. Staring Back is, at that, an image archipelago, dispersed over continents horizontally and demolishing time vertically . . . ” Horrigan and fellow essayist Molly Nesbit clearly speak Marker’s language.

That can be a problem. With all due reverence, I—to be honest—sometimes wonder whether there is not something coy and self-indulgent in the private mythology Marker has been spinning over the years: his grinning cats, his owls, Guillaume-en-Egypte, his female assistants . . . And the somewhat loose hermetic nature of his pronouncements frustrate the essayist in me, who would prefer that he grapple with what he seems to mean and wrest as much clear understanding as can be had. It strikes me as peculiar that our greatest essay-filmmaker should traffic so willingly in the enigmatic, the borderline-sentimental, and the faux-naïve.

What also disturbs me is that those who have personal access to the Master, through e-mail correspondence and personal visits, have set up such a fond protection wall around him against critical judgment, accepting everything that emanates from him as a kind of indivisible pre-posthumous miracle, that it inhibits the making of distinctions about his stronger and weaker expressions. On the other hand, maybe I should just calm down and accept whatever is given me from Marker’s reshuffling of archives in the proper spirit of gratitude.

The tendency for some readers (I know it was mine) will be to try to step back from the Marker mystique and ask: are these good photographs, looked at from the standpoint of art photography? Some are, yes, extraordinarily well-composed and effective, some are muzzy and have little more than a family-album-snapshot appeal. But then, even in his films, Marker has never adhered to Antonioni-esque standards of the beautiful shot. Many of his images are perfectly serviceable, adequate conveyers of information about, say, a Japanese toy or a passing face, designed to be merely a sign in a mosaic of signs. Also, since most of the images here originated as moving-picture frames, they often lack the crisp background information or all-over intentionality of a well-made still photograph. What they do demonstrate abundantly is Marker’s endless curiosity about human (and animal) physiognomy, and the shy, seductive promise of what Buber called the I-Thou encounter.