Remembrance of Things to Come

“If a man has learned to think,” wrote André Breton, “it hardly matters what he is thinking. At bottom, he is always thinking about his own death.” Breton is a recurring presence in Chris Marker’s new video, Remembrance of Things to Come (Souvenir d’un avenir) though the filmmaker himself—an extremely agile thinker at 81—sidesteps, or at least suppressed, direct contemplation of his own mortality while searching out historic ghosts, clues, and portents of tragedy in the work of departed colleague Denise Bellon, French photojournalist and world traveler in the Thirties, a time “when post-war was becoming pre-war.”

Throughout the Thirties and Forties, Bellon photographed Paris streets and World’s Fair exhibits, made portraits of Breton and other surrealists, and chronicled the childhood of her two adorable daughters, one of whom, Yannick Bellon, shares a directing credit on this film. Also, as a member of the Alliance Photo agency (precursor to Magnum), the photographer managed to get out of the house a good deal, documenting Africa under French colonial rule, Legionnaires in Magreb, prostitutes in Morocco, military preparations in Finland. Being Jewish (née Hulmann), she waited out the war in Lyon—“capital of the underground,” Marker informs us—but by 1944 she was at large in the Pyrenées, recording an “insane” and all but forgotten Republican attempt to reconquer Franco’s Spain.

Remembrance of Things to Come is a lovingly opaque tribute to Bellon, a virtual rummage sale of her life’s work, but the film’s full power and reach have everything to do with Marker’s ability to see impending doom in nearly every image in the photographer’s archive—to conjure connections between Bellon’s subjects and the currents of feeling and through that would carry the world into war. It’s unclear to what extent Marker has learned on his collaborator, since the film’s explicit voice—the flow of narrated commentary—is uniquely, familiarly Marker’s. The mode is discursive, descriptive, quick-witted, dense. The tone is at once tender and stoic. A certain tough-guy nostalgia is somehow enhanced by the fact that Marker’s narrator is a woman (Alexandra Stewart) with a calm, lucid voice. As if emboldened by an air of feminine/feline amusement, intimate asides telescope into riffs of wide-ranging speculation. And, clothed in this voice, Marker’s stern aphorisms become seductive.

Remembrance of Things to Come

On Bellon’s vocation: “Being a photographer means not only to look but to sustain the gaze of others.” On Marcel Duchamp: “He wanted to reveal the vanity of art. One day he’ll be used to vindicate the art of vanity.” On the pomp of World’s Fairs in the Thirties: “It seems that nations on the verge of war make a point of parading their wealth.” On one of Bellon’s last surrealist group portraits: “The history of the century’s end will be that of its masks.”

That said, there’s an engaging, amateurish simplicity to the movie. The filmmakers pan and zoom their way through the photos, with an occasional overlay of film footage—stock shots of wwii aerial combat, a clip from Feuillade’s Les Vampires—and now and then a jarring video cutaway, in color, showing hands flipping through a magazine or a book. A plaintive synth score enforces a mounting sense of dread.

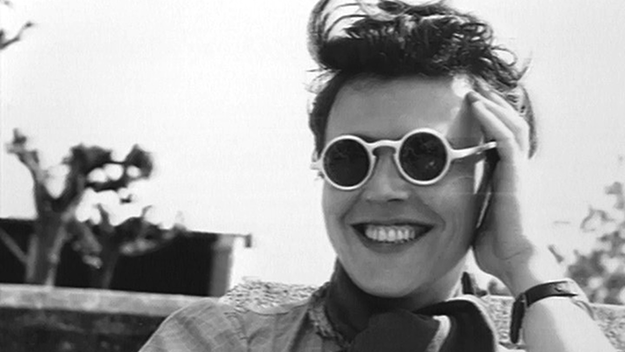

The film serves up a few images of Denise Bellon herself, glamorously young, with a wide, bright smile in every shot. But her eagerness, optimism, and sense of adventure are attributed to the spirit of the time she was documenting; her personal story is implied, or buried, in her pictures. (A perfunctory Google search reveals that she raised her daughters with a second husband, later married a third, and died at 97 in 1999. The filmmakers leave out even these bare biographical facts.)

Remembrance of Things to Come

A more awkward omission, and a significant measure of Marker’s mastery as a conjurer, involves the blunt truth that Bellon as not a particularly remarkable photographer. Her pictures of Dali’s 1938 World’s Fair show do not compare favorable with the lush and loopy photos by Eric Schaal recently collected in Salvador Dali’s Dream of Venus, documenting the artist’s 1939 exhibition in New York. In the massive Modern History of the Surrealism Movement, just issued by Chicago University Press, totaling some 750 pages, Bellon’s work is neither cited nor seen. Unlike, say, Lee Miller, one of the era’s truly gifted camera-carrying icons, Marker’s muse did not possess an extraordinary eye. Perhaps this makes Marker’s project more interesting. Bellon was, simply and mysteriously, a solid witness, a reliable observer in remote locations, a photojournalist whose pictures become revelatory only when re-captioned, nearly 70 years later, by a poet.

All the same, there’s cause to concede that Remembrance of Things to Come register as a retreat from Marker’s essay/portraits concerning fellow filmmakers Medvedkin (The Last Bolshevik) and Tarkovsky (One Day in the Life of Andei Arsenevich). You could take these earlier films, like the new one, as brilliant, unorthodox slide lectures, but they also work as poignant posthumous extensions of the friendships they recount and the careers they review. They’re probingly personal, searching, playful, even quarrelsome. They make their points with riskier cinematic conceits and feature more direct evidence of Marker’s affection and sense of loss, making this current project seem tame by comparison. To what extent did Marker know Bellon—or Breton, Duchamp, Henri Langlois, or any of the other figures appearing in this film? He’s self-effacing enough to steer clear of personal admissions.

But a tame Marker film is wild by any other standard, and invaluable under any circumstance. And this latest happens to weigh in with heightened relevance. Depicted as a recording angel, a sidekick to Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History blown backward into the future, Denise Bellon provides a portrait of a world under the cloud of unseen and inevitable war. You don’t have to look too closely for dire parallels with the current era, or to feel, with Marker, an implicit ache and awe shadowing the spectacle of people and things that no longer exist.

Remembrance of Things to Come

I happened to be in the audience when Marker presented The Last Bolshevik at the San Francisco International Film Festival in 1993. I knew of his identification with cats and owls—evasive, predatory creatures—and his aversion to being photographed (the man can be glimpsed in a sake bar, hiding behind a napkin, in Wim Wenders’s Tokyo Ga). A surprise to see Chris Marker in the flesh, an impish figure, unaffected and even comical, with a quick stammering voice and a giddy air of agitation—a Gallic Woody Allen. I hovered in the small crown gathered around him after the screening. As if his shyness protected him from close scrutiny, I remember his hands better than his face. He was clutching his video camera, one of the earliest compact models, which he confessed to love and take with him everywhere, like a cherished pet. At one point he set it on a table (his knobby knuckles never far away) and, grinning, compared the camera to a cat. I wondered then—and still wonder, up to a point—why he chose to entrust the narration of his films to people with calm, neutral voices. The films would be so different if he narrated them himself! But maybe he considers his work already brimful with his own personality. Maybe he has a dream of himself as an objective, lucid, level-headed observer. Maybe he simply prefers to hear his words spoken by Alexandra Stewart. In any case, plainly enough Marker is intent on rejecting the false authority of routine documentary voiceover, trading standard (masculine) assurance for something quieter, deeper, more questioning, and, not incidentally, more poetic.

While we’re somewhere near the subject, I find it curious that Marker, in this new movie, salutes Breton as a connoisseur of visual images (“He had a perfect eye, as some have perfect pitch”) and quotes him at length, but never gets around to confessing an appreciation of Breton as a conscience for his generation, a voice combining moral imagination with lyrical impulses, a poet pushing the boundaries of everything he undertook. Who other than Chris Marker, on his own idiosyncratic terms has carried this voice into filmmaking and into the current, perilous century? Taking in even his simplest movie—crammed with inklings, warnings, and recognitions—it’s impossible not to feel a rush of gratitude.