Cannes ’94: The Cowboy and the Lady

Just up the Côte d’Azur from Cannes, nestled in a pocket of southern France but legally distinct from it, is the principality of Monaco. In this Ruritanian resort, the moneyed elite convene to play baccarat, race cars, and bask in the remembered radiance of a princess aptly named Grace. Cynics saw Grace Kelly’s marriage to Prince Rainier as a brilliant promotional device—a Hollywood star imported to Monte Carlo as a human tourist attraction on permanent display. In fact, it seemed a successful union of two people. But it was also a perfect metaphorical match. It wed two countries, two complementary styles, two forms of 20th century aristocracy American glamour and French hauteur. For those who followed the Rainiers through 25 years of tabloid ups and downs, the marriage was a widescreen romantic epic, Franco-American style.

The Princess died in 1981, and Her Grace has been deeply missed. But in a happy inspiration for this year’s 47th edition of the Cannes Film Festival, general delegate Gilles Jacob conjured up another French-American wedding. He persuaded Clint Eastwood to preside over the 10-member festival jury, and Catherine Deneuve to serve as vice president. Hollywood grit consorted with Parisian delicacy on the shores of the Riviera. The cowboy and the lady would help sort out which film has received what citations, but their more important function was to serve as complementary icons, emblems of the two dominant picture-making modes: the tough and the tender, the kinetic and the cerebral, the movie with hair on its chest and the film with a brain in its head.

During this balmy fortnight, which ended two weeks before the 50th anniversary of D-Day, the stormy symbiosis of America and France was everywhere visible. Movie people from both countries were still riled up about last year’s GATT conference, when the French insisted on retaining a tax on foreign (read: American) movies as a subsidy for French film production. The wounds had not healed from that fracas, or from the comment that Unifrance’s Daniel Toscan du Plantier had made, perhaps ironically, that January’s Los Angeles earthquake was God’s punishment of Hollywood for wrangling over the tax. Some thought the world’s dominant movie industry was retaliating by sending fewer of the films and stars that give the festival its celebrity oomph. There was a simpler explanation: Hollywood’s big summer movies weren’t ready, and its little winter movies weren’t very good. Studio bosses will always send their product and their performers to Cannes if they think they can profit from the exposure; they will skip the trip if there’s no money, promotion, or prestige to be gained from it. Strictly business, mes amis. No hard feelings. No big trade-war deal.

Certainly the closing-night prize-giving was fraught with geopolitical symbolism: France and America locked in uneasy embrace. For most of the televised hour, Eastwood was mute as Deneuve and mistress of ceremonies Jeanne Moreau introduced guests and winners and coped valiantly but vainly with the technical glitches and gaffes of taste that unaccountably plague this annual TV show. (Why is it that the French—the world’s suavest hosts and most glamorous people—are clueless when it comes to throwing parties on the first and final nights of their own huge festival?) Then Clint stood up and announced that Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction had won the Palme d’Or. The general reaction was of astonishment and anguish, primarily from the many French critics who had favored Nikita Mikhalkov’s overblown, entirely too exuberant Russian film Burned by the Sun or a French-language film, Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Trois Couleurs: Rouge.

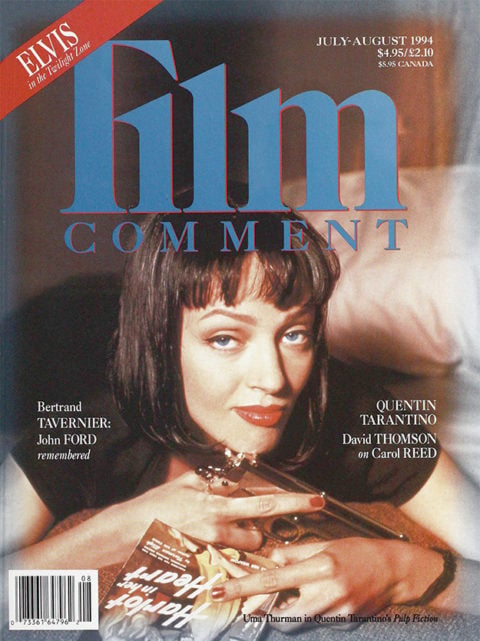

Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994)

Rouge, capstone to Kielowski’s Blue-White-Red trilogy, is an impeccably made minor work, superior to a few of the winning films, and Jean-Louis Trintignant, looking heroically haggard, gives a pristine performance as a retired judge who now passes judgment on his neighbors while listening to their bugged phone conversations. But it is not as if the French were ignored. Until the climactic moment, no American film or star had won a scroll, while a pair of French films had received two awards each. Conspiracy theorists noted that one of these films featured a cameo by Gilles Jacob, and that the jury was stacked with three French representatives—a producer and a critic, in addition to Deneuve. The theorists might have added that the two French films that did win were deplorable.

Produced by Claude Berri, the country’s most powerful movie mogul, Queen Margot took the Jury Prize. (“It must have been the Menendez jury,” said one American critic.) Set during the Medici family’s rapacious war against the French Huguenots, the story has the makings of splendid melodrama: Romeo and Juliet meet The Godfather. But director Patrice Chéreau gets stranded down those dimly lighted Louvre corridors; his film is a dank hodgepodge of palace intrigue, wandering aimlessly, endlessly for two and a half hours. Isabelle Adjani is a wan mannequin as Margot, Daniel Auteuil looks scruffy as her unloved husband, and in the role of Margot’s rabble-rousing lover, Vincent Perez is sexy but empty as a rebel without his clothes. Only Virna Lisi, who won Cannes’s Best Actress prize for her turn as the scheming Catherine de Medici, seems alive. She is foul-mouthed, ill-mannered, old-fashioned Wicked, Witch fun.

Grosse Fatigue (Dead Tired), which won Jury awards for screenplay and technical achievement, is the second feature directed by Michel Blanc, a gifted and engaging actor who goes crazily wrong here. A cautionary fable about movie fame, with Blanc playing a movie star named Michel Blanc, Grosse Fatigue bubbles with comic promise in its first few minutes: A con man who is Blanc’s exact physical double capitalizes on the similarity by appearing at supermarket openings, strip joints, and the Cannes Film Festival. But when the con man’s raping of Blanc’s actress friend Josiane Balasko is taken as just another plot contrivance, the viewer suspects that the writer-director has lost his moral moorings. Things keep getting grosser, and more fatiguing, with only lovely Carole Bouquet around for eye appeal. And she has no unique personality here: she is just the hero’s sounding board, just shop-window dressing—just The Girl.

The Girl as a story prop is a depressing tendency in Hollywood movies, where guys get to blow up the world, or save it, and women are mostly victims or vixens. Happily, the few American movies shown in the official selection featured strong roles for women: for Kathleen Turner in John Waters’s Serial Mom, and Jennifer Jason Leigh in Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (Alan Rudolph’s fussy biography of Dorothy Parker) and The Hudsucker Proxy (the Coen Brothers’ enthralling tribute to ’30s decor, ’40s Hollywood comedy, and ’50s corporate thick-wittedness). But more encouraging were the festival’s indications that, in the far corners of the Third World, directors are making women’s films—in the best sense.

Grosse Fatigue (Michel Blanc, 1994)

One such was Rice People, Rithy Panh’s Cambodian film. Five years ago Panh made the documentary Site 2, about refugees from Cambodian rehabilitation camps. Freedom, one refugee woman told him, is the ability to choose what to grow on your own plot of land. Children, when asked where rice comes from, innocently replied, “From the UN trucks.” From these comments, Panh was inspired to make Rice People, a story of a Cambodian couple and their seven daughters, a poor family who are devoted to, or enslaved by, the cultivation of rice. The film is potent but languid, savoring each joy and enduring each calamity with equanimity. Women cannot weep, the film suggests, precisely because they have so much to weep over. They keep their feelings inside, and let them bloom there.

Panh, who escaped from Cambodia in 1977, learned his craft at IDHEC, the Paris film school. So did Moufida Tlatli, a Tunisian woman whose lush drama The Silences of the Palace was the sweet surprise of this year’s festival. The film is told in flashbacks as Alia, a 25-year-old singer in Tunisia in the early ’60s, recalls her youth as a servant’s daughter in a palace before the war for independence. Perhaps her father was a prince, but her strong, passionate mother won’t say; she declares herself both mother and father to the girl. “Is a father a name?” her mother asks. “No. It is pain, sweat, love. It is caring, every day.” Alia’s ticket out of this palatial prison is her voice; the prince and his court love to hear her sing about music’s magical powers.

With powerful subtlety, and mixing elements of Upstairs Downstairs and Stella Dallas into a stew of North African sights and sounds, The Silences of the Palace portrays the life of women in an imperial land—“the colonized of the colonized,” as Tlatli calls them. The director is properly critical of the imperial past, but also rhapsodic about the emotional drama played out within its luxurious walls. Life before the revolution, no doubt, was decadent for the upper class, demeaning for the servants, appalling for the mass of the poor outside. But any film set in those dead days has to ravish the eye with splendor, for the rich were careful to surround themselves with exquisite objects: the furnishings, the food, the music, the women who made the Prince’s bed and, at his lordly whim, lay in it. Few sights are more spectacular than the smile of Hend Sabri, the beautiful young actress who plays 11-year-old Alia. It is a smile to warm a sultan’s libido and touch a moviegoer’s heart.

The pursuit of art is one way to escape sexual colonization. A more direct route is armed revolt. Bandit Queen, written by Mala Sen and directed by Shakhar Kapur, tells the true story of Phoolan Devi (Seema Biswas), a low-caste girl in 1960s India, when the common wisdom was that “animals, drums, low castes, and women are worthy of being beaten.” Phoolan was sold as a man’s bride when she was 11, discarded, raped, and publicly shamed by the man’s village, then abducted and abused by bandits. She eventually became a bandit’s lover and cohort. Achieving the legendary status of Amazon warrior, she terrorized the upper class and, in an act of sexual revenge, led the massacre of 30 men. Phoolan Devi surrendered to the government on her own terms in 1983, and was only recently released from prison. She plans a career in politics.

Kapur, who shuttles between England and India as an actor, director, and television presenter, has painted a stark backdrop to Phoolan Devi’s sufferings and crimes. The arid ravines around the River Chambal allow no prettifying of the story. Kapur does not stint in dramatizing the sexual atrocities to which Phoolan Devi was forced to submit. Bandit Queen, an astonishingly bold assault on the timid conventions of Indian cinema, has been banned at home. Kapur came to the festival in the hope that, if India will not attend his tale, the rest of the world will.

Bandit Queen was not the only film without a country; the habit of socially conservative or politically repressive governments to ban their best artists is, alas, widespread. Each May, Cannes becomes a very chic refugee camp for unwanted films and filmmakers. One member of this year’s jury was South Korean director Shin Sang-ok, who in 1978 was kidnapped by the North Koreans and, he says, compelled to make films for Kim Il-sung’s fledgling movie industry until he escaped in 1986.

One Chinese director, Yin Li, was explicitly warned to stay home; if he were to present his film, The Story of Xinghua, he would suffer the same fate as Tian Zhuangzhuang (The Blue Kite) and six other directors who this spring were forbidden to make films in China. China’s preeminent director, Zhang Yimou, thought it wise not to accompany his To Live to Cannes; he feared that, if he came, his film might be held up for years in the limbo of the censors’ silence. So To Live was escorted by its male lead Ge You (who won the Best Actor award) and Gong Li, star of all six of Zhang’s films. Like The Blue Kite and Farewell My Concubine, To Live dramatizes multi-generational life under Mao: the imposed idiocies and betrayals and, amid all these convulsions, the personal bonds of love and trust. Because it spans 30 years in one family’s life, the new film denies itself the impact of Zhang’s Raise the Red Lantern. It is a national tragedy played in a minor key, a sonata for soldiering on.

Bandit Queen (Shekhar Kapur, 1994)

However suppressive of free speech the government position may be, the Chinese film renaissance continues to flourish, on the Mainland and elsewhere. He Ping’s Red Firecracker, Green Firecracker is a seductive, sumptuously realized story about the volcanic affair between a young woman (the beautiful Ning Jing) who has been bequeathed the family business of making firecrackers and a moody artist in her employ. Huang Janxin had two provocative films in Cannes: The Wooden Man’s Bride, a kind of Eastern Western about a man, forlornly in love with the lady of the house, who becomes a bandit and returns to claim her, and Back to Back, Face to Face, a gentle but pointed comedy about a master gamesplayer in the Chinese bureaucratic maze. And for pure narrative pizzazz, no film at Cannes could match Ronny Yu’s Hong Kong action extravaganza The Bride with White Hair, starring Leslie Cheung of Farewell My Concubine and the gorgeous Brigitte Lin. Strutting through her troubles and twirling magically in the air, Lin was the strongest, most appealing woman on screen in Cannes.

Rules of fair play required that the festival have a few token films about men. Giuseppe Tornatore’s A Pure Formality appeared to fill that bill, but that was one of the film’s many deceptions, for Tornarore’s subject is not so much men as it is man’s fate. This is a chamber play, both figuratively (since it takes place in one room, a detention chamber) and literally (since it begins with a gun’s chamber emptying its bullet into an unidentified body). Gérard Depardieu is staggering zombie-like toward a prison that looks like a castle. His interrogator, Roman Polanski, seems pleased to recognize him as the distinguished writer Onoff and to quote from memory extracts from the author’s work and life. This is not a whodunit but a whoizzit, and maybe a where-are-we. The film plays like a Kafka-esque blend of No Exit and The Devil and Daniel Webster, and fiddles with memory and fantasy, talent and reputation, life and death, as easily as if they were a light switch on-off.

A Pure Formality was one of three Cannes pictures with the same premise: a man honestly can’t remember if he committed a horrible act. The other two were American independent films, Suture (an entertainingly pretentious melodrama already in U.S. release) and Hal Hartley’s Amateur, a deadpan delight. Isabelle Huppert, just out of the convent, is a virgin nymphomaniac, and Martin Donovan the wounded man she hopefully rescues. Probably he is a vicious gangster who abused his porn-queen wife; possibly, to an ex-nun desperate for someone to need her, it doesn’t matter. Inside these thriller trappings lurks Hartley’s best film, with smartly off-kilter characters and an off-Broadway tone that is smartly realized by Huppert, Donovan, and the damply charismatic Elina Löwensohn as the ex-wife. In this sly meditation on friendship and identity, the message is that you can never count on either one—but you might as well try.

Cinema, a two-way mirror into bigger-than-life behavior, takes naturally to stories of erotic and emotional extremes. And, as in life, the oddest stories have the deepest roots. The fascinating Exotica, from Canadian writer-director Atom Egoyan, brings together a band of tortured folks in an elaborate nightclub where the women disrobe and talk intimately to the customers. The club seems weird, but it’s really a place where a man can try to create a surrogate family life—where he can be father, lover, and friend, for a few moments, for a few dollars. Complex in its time-warp structure, profound in its revelation of family ties and dark desires, Exotica is about people seeking a fantasy world as an alternative to the real one, over which they have little control, from which they see no escape. As one character says ruefully,“Not all of us have the luxury of deciding what to do with our lives.”

And that may be Hollywood’s great contribution to the world’s fantasy life. Nearly all its screen creatures, good or evil, get to decide what to do with their lives, and then get to play out their dream scenario. That is the subtext of Pulp Fiction, in which Tarantino takes some of the oldest conventions of the hard-boiled genre—the gangster (John Travolta) on a date with his boss’s wife (Uma Thurman), the aging boxer (Bruce Willis) who refuses to throw a fight, the problem of disposing of a corpse—and twists them till they scream like new, while making sure that every character gets dignity and satisfaction.

In stunning fashion, Tarantino fulfills the promise of Reservoir Dogs. The film looks great and moves at a gallop—no small achievement considering that the wide screen is usually filled with two people talking. But it’s the voluptuous, convoluted, obscene talk, the talk of violent men who want to be philosophers and prophets, that Tarantino loves. “When you scamps get together,” says Thurman of a couple of gangsters, “you’re worse than a sewing circle.” They talk about fast food (“Hamburgers. The cornerstone of any nutritious breakfast”), about the conundrum of beautiful women (“It’s a shame that what is pleasing to the touch and pleasing to the eye are rarely the same”). All the actors do justice to the script. Travolta, Thurman, and Willis redeem their careers, and as a vicious thug “in a transitional phase,” Samuel L. Jackson commandeers the film with his steely presence. What a pleasure it must have been to speak those lines, be those characters. It would be delightful to see a making-of documentary on Pulp Fiction.

Exotica (Atom Egoyan, 1994)

One of Cannes’s breakthrough films was a fictionalized making-of movie. Abbas Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees purports to be a behind-the-scenes look at the production of the Iranian director’s previous film, And Life Goes On. In fact, it is a sweet, microscopic story about Hossein (Hossein Rezai), a young bricklayer with a bit part in the movie, and Farkonde (Farhad Kheradmand), the uppity girl he loves. Kiarostami takes his time laying the bricks of this film, but the ultimate edifice is beautiful, with a four-minute final shot that is funny, touching, and breathlessly suspenseful. “Dreaming may be the most necessary thing in life,” Kiarostami has said. “If someone tells me one day, ‘You have to choose between dreaming and seeing,’ I will probably choose dreaming.” Hossein can’t see straight—the girl he’s crazy about keeps rejecting his troths—but he can dream, can’t he? And in the final shot, his dream can come true. Perhaps.

Movies give their maker the power to realize nightmares as well as daydreams. In the first two of the three episodes in Nanni Moretti’s modest, magnificent Dear Diary, the Italian actor-director daydreams on film. His offhand movie diary includes a ride on his Vespa through the streets of Rome, trips to the islands where L’Avventura and Stromboli were made, and a melancholy ride to the site where Pasolini was murdered. He stops American actress Jennifer Beals to tell her how Flashdance changed his life. He describes his new film project, a musical about a Trotskyite baker in ’50s Rome. Appalled by Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, he imagines torturing the critic who reviewed it favorably by forcing the fellow to listen to excerpts from his silly essays. In one priceless sequence, dozens of adults try phoning their friends but are intercepted by the friends’ tyrannical kids. It is a hilarious commentary on the plague of the pampered child.

Then, in the final episode, we are forced to confront issues of life, death, and an incompetent medical establishment. “Nothing in this chapter was invented,” Moretti tells us as we see him fit for a chemotherapy cold cap. The director had a nagging itch all over his body; when he consulted doctors they diagnosed a hundred different ailments and prescribed a thousand useless pills. One medic declared, “I will bet one of my testicles that it’s cancer of the lung.” Moretti finally discovered he had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, from which he says he was cured. In the last shot, he says that his treatment now is to drink a glass of water with his morning coffee.

To face these issues with such deadpan equanimity, like Buster Keaton staring down a plague, shows great strength. To make a beautiful film from his travail shows the hand of a great artist. And an innocent one. “Children dream with open eyes,” he says, “as when they were told heroic tales.” Dear Diary is a heroic tale, told with a child’s wide-eyed wonder. May it have a happy ending.

By a poignant coincidence, Dear Diary was screened in Cannes on the day Jacqueline Onassis died in New York, thus linking two profoundly moving case histories of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The world had lost a glittering celebrity, and grieved for her as it had seen her grieve 30 years ago. News of her death—which was covered as widely in French newspapers and television programs as it was in the States—inevitably summoned old images of a young woman who had brought to Camelot a movie-star elegance and a love of all things French. One recalled that, in the White House screening room, Jack Kennedy would want to watch Hollywood action pictures, while Jackie preferred Jules and Jim. Mr. and Mme. President were a movie-star couple, a handsome amalgam of American and French tastes, no less than Clint and Catherine, or Rainier and his Grace.