In the Desert of Digital

Why, wonders the privileged critic, does the Cannes Film Festival seem so much less necessary than it once did? Is it just me? Am I too jaded and tired? Did dehydration play a part? This year, with the increased security checks, it was impossible to smuggle a bottle of water into the theaters of the Palais, and with almost all of the water coolers removed from the complex, presumably for security, one often went from screening to screening without anything to quench one’s thirst except the free coffee from the Nespresso bar, which had the opposite effect.

Of course, hydration matters. But the real culprit is digitization, from which there is no turning back. Not that many years ago, the glory of Cannes was not simply the selection, but the way the chosen films looked on the big screens of the Lumière and the Debussy. The 35mm projectors were state-of-the-art, and the projectionists were artisans in their own right. Filmmakers came to the theaters the night before their screenings to confer with them and to check the sound levels, the frame format, and the color temperature of the projector bulbs. One evening in 2000, after the final screening in the Debussy, I ran into Wong Kar Wai in the lobby, waiting to check the first reel of In the Mood for Love. The next day we would see one of the most exquisite films in cinema history, projected in the most perfect way possible.

Now every film in the Lumière and the Debussy is projected from a DCP. That’s not the festival’s fault. Almost all theatrical release films, whether they’re shot on film or digital, are digitally post-produced and exhibited on digital formats. I’m sure that Cannes has the finest digital projectors available, but that doesn’t make the image significantly more exciting than what you see on the best big screens in cities around the world, or on a professional studio monitor in your living room. Digital projection is death in motion—as if all the light in the image has been sucked into a black hole. Looking at four or five digitally projected movies a day is depressing. Yes, we’ve become acclimated to digital, and many relative newcomers to Cannes have no memory of anything else. But there is a reason that vinyl is back. People are sick of listening to their music digitally, even if it’s convenient. And overdosing on digital movies is just as sickening.

Gimme Danger

Putting this unscientific analysis of digital OD aside, the film selection was not so hot either, although the competition boasted one extraordinary film, Maren Ade’s audacious, hilarious Toni Erdmann, a screwball comedy of remarriage in which the twosome is an aging-hippy, prankster father and his corporate-ladder-climbing daughter. Ade much more than fulfills the promise she showed in her first two features, which, as I remember, weren’t funny at all. Here she pulls out all the stops, from the opening wacko masquerade to the inspired series of comedic setpieces that end the movie, leaving one poised between laughter and tears. It was disheartening—no, it was completely fucked-up—that the festival competition jury awarded no prize to Toni Erdmann, which was by far the most popular film in the competition and which did the near-impossible by uniting entertainment-oriented and art-oriented viewers. But the less attention given to this jury the better.

Toni Erdmann was one of three female-directed films in the 21-film competition, which is a marginally better proportion than last year. Of the other two, I missed Andrea Arnold’s American Honey but forced myself to sit through Nicole Garcia’s From the Land of the Moon, a ludicrous post–Marguerite Duras soap opera with an unbearably schmaltzy score—as if Marion Cotillard’s precise enactment of frustrated sexual desire needed a musical boost. If that sounds negative, Garcia’s film was far more tolerable than the competition selections by at least four lauded male directors, specifically Xavier Dolan, Bruno Dumont, Sean Penn, and Nicolas Winding Refn.

Despite the small number of films by female directors, Kering, the foundation chaired by fashion mogul François-Henri Pinault “to support women through partnerships with NGOs and social entrepreneurs,” nevertheless made it seem as if Cannes was a hotbed of feminist activity, albeit one led by gorgeous movie stars in five-figure gowns. Kering’s partnership with Variety insured its blanket promotion in a festival where reading the trades is an early-morning ritual. But Variety, well on its way to destroying its own brand, came out looking like Women’s Wear Daily. Kering’s two practical accomplishments were giving awards to three emerging Middle Eastern female directors—Leyla Bouzid, Gaya Jiji, and Ida Panahandeh—and starting a debate about whether a quota system should be applied to government funding for the arts and education (hardly relevant in the U.S. where such funding is virtually nonexistent). Honored on the 25th anniversary of Thelma & Louise, Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon acknowledged that their hope for the film to be the start of something hadn’t yet come to pass. Chloë Sevigny added her acerbic wit to the Kering events, saying that she preferred working with women to almost any of the celebrated male directors whose films she’s graced in the past two decades. Sevigny’s directorial debut, Kitty, was the standout in a Critics’ Week program of three short films by actresses. Adapted from a story by Paul Bowles, it meanders a bit at the beginning but then takes a turn that haunted my dreams for days.

Kitty

Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson rivals Toni Erdmann for the festival’s most audacious and pleasurable film. Both are comedies, but where Ade’s film sprawls and succeeds via its script and larger-than-life performances, Jarmusch’s is pared down, like a great three-chord rock song that transcends through repetitions and minute variations. The film’s title is a multi-purpose referent. It’s the name of a town in New Jersey; the title of a poem by William Carlos Williams, named for this same town where Williams lived, wrote, and practiced medicine; and it is the handle of the film’s protagonist, played by Adam Driver, who spends his workdays, uh-huh, driving a bus up and down the main drag of Paterson, his birthplace and the film’s only location. Like his idol, Williams, Paterson writes poetry that takes its inspiration from daily life on the job. But Paterson, the movie, is more contained than Paterson, the epic poem. It’s closer to Williams’s minimalist The Red Wheelbarrow—16 words, eight lines, four stanzas, constructed as a prescription for making art. “so much depends / upon / a red wheel / barrow…” writes Williams. For Jarmusch, who divides Paterson into seven stanzas, one for each day of a single week in the life of the bus driver/poet and his wife, Laura (Golshifteh Farahani), so much depends on the particular quality of the light that falls on the bed where Paterson wakes up every morning next to Laura, and also on the angle from which we see the two of them, dreaming separate dreams that are shaped by their connection to each other. Each morning is the same and different. And rapturous. Jarmusch and DP Frederick Elmes find a lyricism in digital images that’s different from what’s been achieved in film—and makes comparison beside the point.

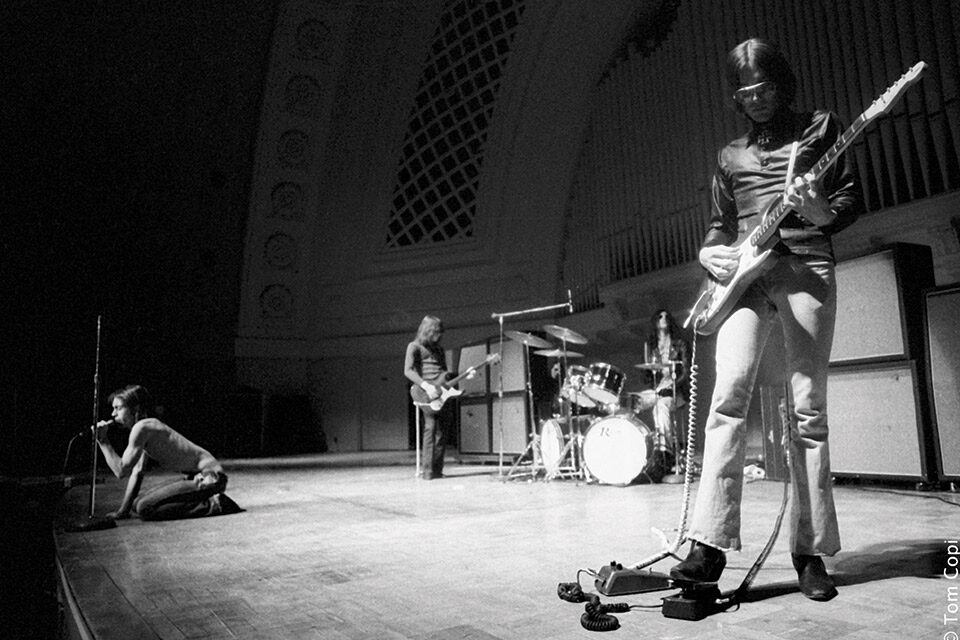

By the way, my most memorable Cannes moment was walking up the red carpet with The Stooges blaring from the speakers. It took The Stooges to make me forget my fear of tripping over my Dr. Martens–shod feet. The ticket invitation to the midnight screening of Jarmusch’s Iggy Pop documentary Gimme Danger said “appropriate dress,” which I took to mean Comme des Garçons jacket, black jeans, and combat boots. (No one asked me what I was wearing, so I’m telling you now.) Jarmusch’s tribute to The Stooges, an even bigger influence on him than Williams and the New York School poets he inspired, is as unexpectedly quiet and thoughtful as its central figure, Iggy Pop, né James Newell Osterberg Jr., although its performance clips of choice songs (“I Wanna Be Your Dog” and “I Got a Right” among many) are proof that the music is timelessly electrifying and deserved the 15-minute ovation Iggy and Jarmusch received at the end of the night.

Jarmusch went home unacknowledged by the competition jury, although Nellie, the English bulldog who played Marvin, the third party in the marriage of Paterson and Laura, received the annual Palm Dog award. Nellie’s hangdog face made her the quintessential Jarmusch actor, but she also benefited from Jarmusch’s perfectly timed editing, just as Kristen Stewart’s riveting non-performance in Personal Shopper resulted from the collaboration between the actor and the director Olivier Assayas, whose timing and shot selection is impeccable. The only deserving film to win a nod from the competition jury (Assayas shared the directing award with Cristian Mungiu, whose Graduation is solid but hardly as adventurous as his three earlier features), Personal Shopper is as ephemeral as the ghost that haunts the imagination of Maureen (Stewart), whose recently deceased twin brother had mediumistic powers. In the opening sequence, an intricate construction of sound/image relationships, Maureen, alone at night, walks through her brother’s old country house, looking and listening for traces of his presence. Later Assayas serves up a Hitchcock-worthy sequence in which Maureen is terrorized by text messages that follow her from Paris to London and back again. Personal Shopper proved surprisingly controversial; critics in their twenties scorned Assayas for his “recent discovery of smartphones.” What some of us oldsters understood is that smartphones have rendered the classical who-knows-what-and-when-do-they-know-it construction of thriller plots inoperable. In response, Assayas creates suspense, not simply by having Maureen plagued by texts from an unknown source, but by blinding her to the possibility that the sender is very much alive and dangerous because she wants to believe that the messages come from beyond the grave. In the end, Personal Shopper, whose lineage stretches backward through Chris Marker’s Level Five to Vertigo, is about existential loneliness and the failure of connection in a connected world.

Sieranevada

If Stewart’s particular screen acting gift allows her to function convincingly as a medium for narrative forces that her character neither fully understands nor controls, in Paul Verhoeven’s Elle it is Isabelle Huppert who runs the show. Verhoeven would not have a film with-out her. As adept in the comedy of sadomasochism as she has been in melodramas and tragedies along the same psychosexual spectrum, Huppert plays Michèle, who has escaped from publishing into the more lucrative field of video games. The film we are watching may or may not be analogous to the most successful game she’s produced and the ones she will produce in the future. In the opening sequence, Michèle is surprised by an intruder who rapes her. The rapist is dressed head to toe in black rubber; the rape itself involves a lot of slapping and punching. It would be just plain terrifying except that the rapist flees without pulling up his pants completely and his exposed muffin top is the tip-off that this is sex as comedy, replete with ambiguity, irony, and, eventually, consequences for the rapist. Make no mistake, the comedy is dark, but Michèle, who’s at least as damaged as everyone around her, takes control, or at least as much control as the ambivalence of her desire allows. Elle walks the sexual-politics tightrope with sophistication and wit, largely thanks to Huppert. It is, at the least, a movie worth arguing about—and seeing again.

Cristi Puiu’s Sieranevada, Mungiu’s Graduation, and Bogdan Mirica’s Dogs testify to the continuing energy of Romanian cinema. Dogs is graced by the always amazing Vlad Ivanov, who here embodies pure evil as if it were no more than a matter of fact. But the most formally audacious and emotionally compelling of the three is Sieranevada. Taking place during a memorial for the patriarch of a large family, it is almost entirely staged in a single apartment of perhaps eight rooms, half of which open off a central corridor. Puiu’s camera, the opposite of fly-on-the-wall, is in constant movement, wandering through the apartment, panning left and right, tilting up and down, making its dispassionate presence known to us, if not to the characters in the film. We’ve seen cameras move like that before—in Michael Snow’s Back and Forth, or in one scene in Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, in which the camera roams a corridor where people on the brink of disaster are playing musical beds. But to separate camera from narrative, thus distancing us from the drama without diminishing its punch, takes nerve, virtuosity, and an appreciation of how movies create and mediate emotion via movement in space. The most seductive movies in Cannes played with form so that the human comedy—the comedy of mortality—was made strange and new.

Amy Taubin is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and Artforum.