Suffer the Children

The strongest Cannes Film Festival in recent memory—at least in the nine years I’ve been attending—concluded with an unusually satisfying distribution of prizes by the Robert De Niro–led jury (which also counted Uma Thurman, Jude Law, Johnnie To, and Olivier Assayas among its members). Even the third-place Jury Prize awarded to French actress/director/hot mess Maïwenn’s ensemble drama Polisse was made bearable by the spectacle of its bewildered creator, tangles of unkempt brown hair falling wildly about her—and a bright red dress valiantly struggling to stay attached to her body—taking to the stage, personally embracing every member of the jury, then panting her way through an acceptance speech that might still be going on if the band hadn’t finally played her off.

Following the exploits of the Paris police department’s “child protection unit,” Polisse (which screened early on) helped to establish this year’s Croisette-spanning theme of children in peril, which could be found to varying extents in fellow Competition entries Michael (kidnapping and pedophilia), Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin (teenage sociopathy), Aki Kaurismäki’s universally admired Le Havre (illegal immigration), and the Dardenne Brothers’ Grand Jury Prize co-winner The Kid with a Bike (child abandonment); in the Directors’ Fortnight entry Play (bullying); and in just about every film at the 50th-anniversary edition of the Critics’ Week, from French actress-director Valérie Donzelli’s opening-night Declaration of War (pediatric cancer) to Israeli actress-director Hagar Ben Asher’s The Slut (pedophilia again), the fact-based 17 Girls (teen pregnancy), and the profoundly disturbing Snowtown, which recalled Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer in its verité sketch of Australian serial killer John Bunting, who lured local youths into aiding and abetting his violent crimes throughout the Nineties.

Meanwhile, back to Polisse: for over two hours, Maïwenn’s third feature film assails us with such unpleasantries as a father accused of raping his own daughter (when he tires of sodomizing his wife) and a gymnastics coach who gets a little too close for comfort with one of his young athletes. But for all its ripped-from-the-headlines urgency, Polisse plays out as something close to a histrionic farce, with endless scenes of the detectives themselves verbally and/or physically abusing suspects and colleagues, railing against Sarkozy, and holding forth about their personal lives in the company of a photojournalist (played by the director) assigned to document the unit for a government-sponsored book. An orgy of screechingly over-the-top performances that only an actor-director could orchestrate, so haphazardly shot and cut that you’d think Maïwenn hadn’t so much as seen a movie before (let alone made two), Polisse may have been selected for the Cannes Competition for any number of reasons having to do with its maker’s undeniable je ne sais quoi, but artistic merit certainly wasn’t among them. By the time one character decides to one-up the rest of this hysterical bunch by hurling herself from a top-floor window, most of my more sensible colleagues had themselves long ago bolted for the exits.

Tree of Life

If the Palme d’Or win for Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life struck some in the international press corps as a foregone conclusion, it didn’t stop a few of them, gathered to watch the live simulcast of the Cannes Palmarès in the Théâtre Claude Debussy, from booing as loudly as they had at the film’s official press screening a few days earlier. In discussing Malick’s film—the festival’s hottest topic after l’affaire von Trier—with others before, during, and after the fact, I found many of the film’s detractors clinging to the notion that Malick had, in the interval between The New World and this film, become a born-again Christian. That may well be the case, but, to these eyes, The Tree of Life remains an open, porous, searching work, unmistakably rooted in the tradition of religious art, and yet unbound by any one particular dogma. To which I would add that there seemed to be far less objection when, only last year, the Palme d’Or went to another meditative film about nature, death, and possible afterlives—Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives—perhaps because there is no right-wing Buddhist conspiracy suspected of plotting to undermine Western democracy as we know it.

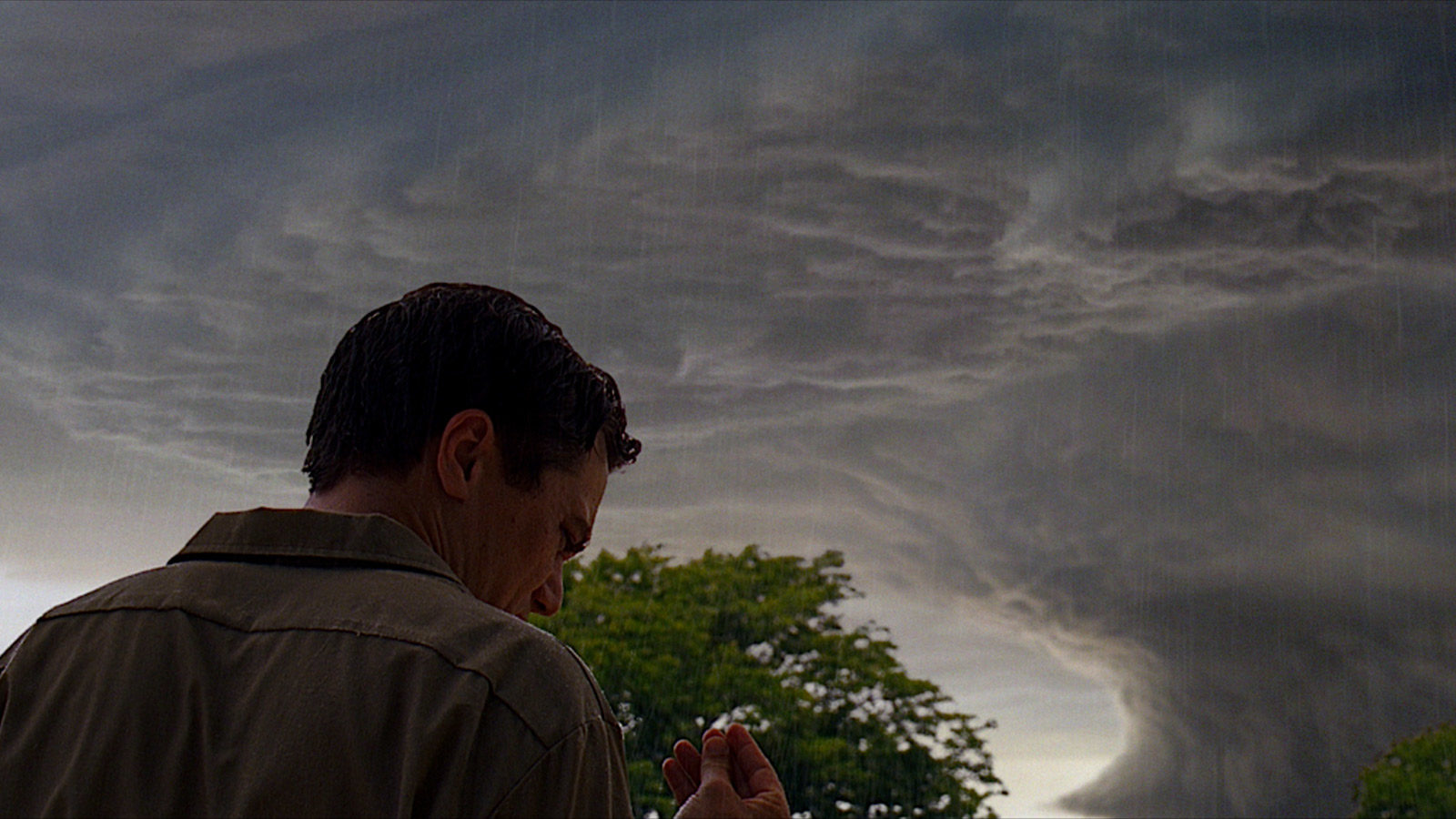

While Malick was busy pondering the very beginnings of life on this planet, two other films set about envisioning the end. At the Critics’ Week—where, in the interest of full disclosure, I served on a competition jury comprised of three other critics and the South Korean director Lee Chang-dong—the highlight of an unusually strong lineup was Take Shelter, the second feature by Shotgun Stories director Jeff Nichols, an acknowledged Malick acolyte whose new film shares a producer with The Tree of Life as well as a leading lady, Jessica Chastain (reportedly at Malick’s personal recommendation). At once genre movie and psychodrama, Nichols’s film unfolds in a stretch of rural Ohio where a blue-collar husband and father (brilliantly played by Michael Shannon) finds himself suddenly plagued by visions of the rapture: strange clouds darkening the sky, acid rain sheeting down from the heavens, flocks of birds in panicked flight. Gradually, Shannon’s nightmares spill over into his waking hours and he begins to question his own sanity, while Nichols builds to an extraordinary climax that, depending on how you interpret it, says either that paranoiacs are sometimes right or that we are all living in a collective delusion.

Nichols has said that Take Shelter was born from a desire to capture an anxiety he felt in the air in the first years of the 21st century, and a certain intangible dread permeates the film—a feeling of Old Testament hellfire and brimstone marbled with the realities of life in today’s America: a moribund economy, healthcare woes, lives surrendered to credit. In the film, Shannon’s character undertakes the construction of a large underground storm shelter—a tip of the hat, perhaps, to The Wizard of Oz, but here, when the violent storm has come and gone, we’re still very much on this side of the rainbow.

Melancholia

Proffering its own end-times vision, the title of Lars von Trier’s Melancholia refers to both a feeling and a planet, the latter on track to collide with Earth, but not before a tony wedding reception has run its course at a palatial seaside estate with a Marienbad garden. In the arresting pre-title sequence, von Trier cuts between this elite enclave (seen in a series of slo-mo tableaux) and the outer reaches of the galaxy, immediately positing Melancholia as a nihilist’s response to The Tree of Life—all physics, no meta. Of course, if his films are any evidence, von Trier has been orbiting Planet Melancholia for a while now, even before his widely reported battle with clinical depression, and so it’s little surprise that the main characters in Melancholia enter the stage with an existential weight on their shoulders that has little, if anything, to do with the world’s imminent demise.

Considerably more surprising is the restrained, elegiac feel Denmark’s reigning agent provocateur brings to the material in both formal and emotional terms. If Dogville suggested a mad scientist’s fusing of Kafka’s Amerika with Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, Melancholia—which impresses me as von Trier’s most significant work since that film—seems to exist at the intersection of Armageddon and Anton Chekhov, oddly accepting in its appraisal of the end of a way of life, and of life itself. Von Trier’s subsequent foolhardy remarks notwithstanding, Melancholia was received with the warmest embrace by the international (and particularly North American) press of any von Trier film in the 15 years since Breaking the Waves. Indeed, when Lars von Trier is cheered at Cannes and Terrence Malick booed, this may be the surest sign of all that the apocalypse is upon us.

Malick and von Trier weren’t the only filmmakers in Cannes who seemed to be engaging in a private cinematic dialogue with one another. Two films—Pater, by the 79-year-old French renaissance man Alain Cavalier, and This Is Not a Film, by banned Iranian director Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb—seemed born from the immortal dictum (usually ascribed to Orson Welles) that “the enemy of art is the absence of limitations.” Each film barely ventures outside the walls of their makers’ own homes, in Cavalier’s case voluntarily, in Panahi’s by enforcement. A lithe, playful exercise that at points suggests a Gallic My Dinner with Andre, Cavalier’s film stars the director himself and the redoubtable French leading man Vincent Lindon as both themselves and, respectively, as the President and Prime Minister of France—a role-playing game they slip in and out of at will, and which fuels a free-flowing discussion of food, globalization, national pride, and neckwear couture. Though the dense local politics seemed to strike some non-French viewers as a bit opaque (even with the arrest of Dominique Strauss-Kahn gripping the headlines), the celebration of friendship, filmmaking, performance, and good conversation in Pater needs no translation.

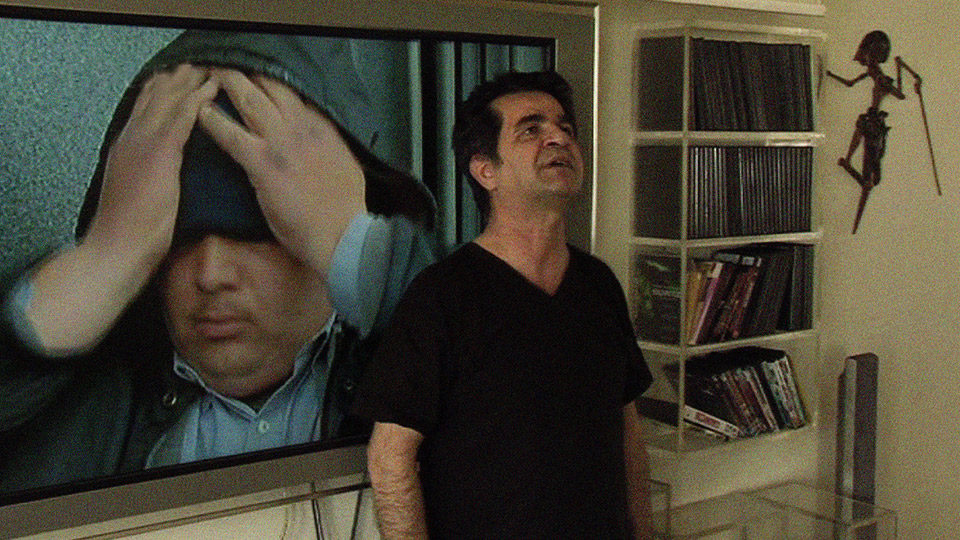

This Is Not a Film

Panahi also appears on screen as himself for much of This Is Not a Film, which begins as a message in a bottle from the shores of house arrest and quickly evolves into something infinitely more complex. At first, Panahi announces that he is going to act out some scenes from the film he was planning to make at the time of his arrest—a Romeo and Juliet–esque love story involving a girl herself kept under lock and key by her strict parents. After a bit of that, Panahi switches to a kind of illustrated autocritique, using scenes from his previous films to explain how he prefers to tell a story—in particular with many layers of self-reflexivity. By which point, it’s clear that we haven’t just been brought into Panahi’s apartment, but into his filmmaking universe, and that This Is Not a Film is very much a film indeed—and a Jafar Panahi film at that.

Of the other top films in the Competition, two invoked driving as a primary motif: Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Grand Jury Prize co-winner Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, an intoxicatingly strange, oblique police procedural in which a caravan of cops spend a very long night winding through the Turkish countryside in search of a dead man’s grave; and Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, a needle drop deep into the groove of a Walter Hill/William Friedkin/Michael Mann neo-noir, starring a terse Ryan Gosling as an unnamed Hollywood stuntman who moonlights as a getaway driver. Reduced by Refn almost to the point of abstraction—it could have been called Notes on a Rehearsal for an Action Movie—Drive may do little to win over multiplex crowds who prefer the fast and furious to the moody and languorous, but it reconfirms Refn as one of the most exciting young directors around, and Albert Brooks (stealing the film as a small-time Jewish gangster with an aversion to loose ends) as a national treasure.

For sheer entertainment value, though, little in Cannes could best Michel Hazanavicius’s The Artist, a black-and-white silent movie about the end of silent movies, starring the rubber-faced Jean Dujardin (a veteran of Hazanavicius’s hilarious OSS 117 spy-movie send-ups) as a vain Hollywood matinee idol who digs in his heels and refuses to adapt to talking pictures. Rooted in a palpable love of cinema, with nary a shot that couldn’t have been achieved using actual Twenties technology, The Artist is the kind of generous art-house crowd-pleaser that nothing—not even the shit-eating grin of its newly minted U.S. distributor, Harvey Weinstein—can stop as it speeds its way toward Oscar night.