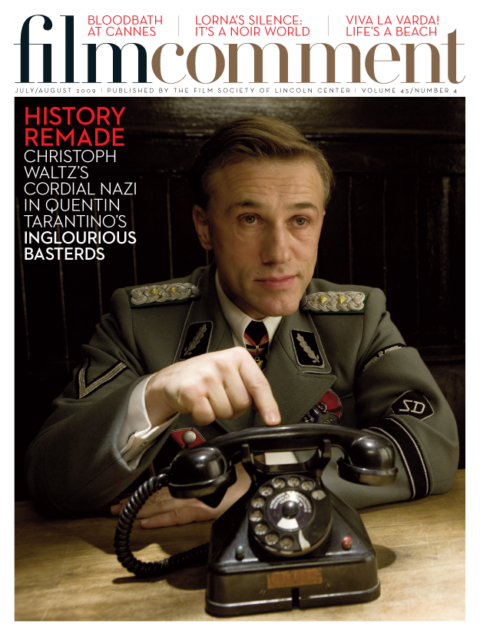

Kinatay

Weeks before I got on the plane to Nice, I was sure that Cannes ’09 would not be a vintage year. On the festival website, a valedictory essay by festival president Gilles Jacob honored Cannes’ commitment to the director as auteur. Well and good, and a bit inspiring, but even the most dedicated auteurist has his/her A, B, and C lists, and for me, Michael Haneke, Lars von Trier, Pedro Almodóvar, Ang Lee, Quentin Tarantino, Ken Loach, and Gaspar Noé, to name the directors of some of the most highly anticipated movies, are far from top tier even when they’re on their game, which, as it turned out, none of them were. What I hadn’t anticipated, however, was that the 12 days would feel as if one were trapped in a provincial production of Titus Andronicus, Shakespeare’s bloodiest play (it contains the infamous stage direction, “Enter Lavinia, her hands cut off and her tongue cut out”).

With one or two exceptions, the Competition films were either gruesome or bland. As the flayed bodies and scalped heads piled up—the cherry on top being a swooping close-up of a screamingly fake aborted fetus swimming in a dish of very real-looking blood—one grew tired of questioning whether the viscera signified anything other than a desperate bid for attention by directors and the festival itself, which has now put its imprimatur on what had been a marginal, or in the hands of a master like David Cronenberg, subversive category: art horror. If next year brings more of the same, I’ll venture that what we’re seeing is world cinema itself bleeding out.

Of course, movie violence is nothing new, and nothing new to Cannes. In 1976, the festival awarded the Palme d’Or to Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver; in 2000, as a celebration of the new millennium, it offered Jean-Luc Godard’s The Origin of the 21st Century, which for 16 minutes rubbed the faces of gala attendees in images that depicted the worst acts human beings have perpetrated alongside some of civilization’s greatest artworks. The violence in Taxi Driver seemed revelatory and necessary when the film was first shown, and just as much so today when America is reliving the mid-Seventies in the form of another failed war, disgraced Republican presidency, and economic recession, and with new incarnations of Travis Bickle picking up the gun in a twisted defense of white male privilege.

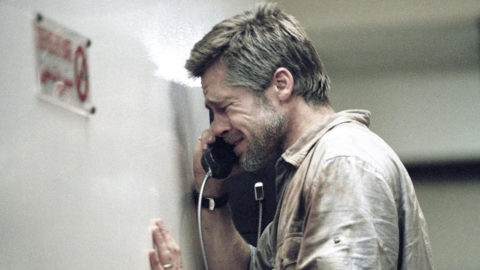

Wild Grass

But when is the depiction of extreme violence necessary and when is it exploitation? Why do we apply different criteria to violence in genre films and violence in art films? And when did the two begin to merge? Taxi Driver is a near-perfect fusion of genre and art. Godard’s Pierrot le Fou, projected digitally this year in the Cannes Classics section, is suffused with genre but is in no sense a genre film. Its gangsters and Vietnam War henchman operate on the periphery of the most emotionally violent and broken-hearted depiction of mad love unto death ever committed to celluloid—the violence expressed in colors so intense you feel them in your solar plexus. Pierrot le Fou is a law unto itself. Luckily, I had seen this restoration recently in New York; had I watched it in Cannes, current cinema would have seemed even more depleted by comparison.

Or maybe not, since the one extra-ordinary film in competition, Alain Resnais’s Wild Grass, rivals Pierrot in its expressive use of color—glowingly saturated Fauve reds, yellows, and greens bathed in meltingly soft, impressionist light—to evoke the romantic imagination on fire. Adapted with notable fidelity from Christian Gailly’s novel L’Incident, the narrative hinges on the French verb voler, which means both “to fly” and “to steal.” A man (André Dussollier) and a woman (Sabine Azéma) connect by chance when the woman’s yellow handbag is stolen and the man finds the red wallet that the thief has discarded. Inside is her pilot’s license. The man, who loves to fly, becomes obsessed with the woman. She rebuffs him, then changes her mind and pursues him—all this turbulence before they’ve said two words to each other. The film is at once buoyant and melancholy, heady and erotic—a delirium of contradictory desires. Eric Gautier’s crane-mounted camera performs remarkable aerial twists and turns. Resnais, a master choreographer of camera movement, has never been this inventive or this free. Wild Grass seems both precision-wound and made up on the spot. It might be his greatest film since Muriel.

Where Wild Grass is a wish-fulfillment dream with a hint of cautionary tale, Lars von Trier’s similarly oneiric Antichrist is grim castration fantasy—and in characteristic von Trier fashion, a grim send-up of the same and of us for relating to it in whichever way we do. His trick of putting the audience in a vise and then ridiculing it for wriggling has worn thin, and since Antichrist is an “intimate” two-hander, the frayed seams are all too evident. Which may be the desired effect, or may not be, ad infinitum, but frankly, it just bored me. The movie opens with a married couple (Charlotte Gainsbourg and Willem Dafoe) having sex, oblivious to the fact that their toddler has crawled out of bed and is heading toward an open window. The scene is rendered in extreme slow motion—the trajectory of the child across the room and onto the ledge and his fall through the falling snow are agonizingly attenuated and the beauty of the image intensifies the horror. That the beauty is a booby trap is signaled, perhaps a mite too obviously, by the familiar heart-tugging grand-opera aria that accompanies the image.

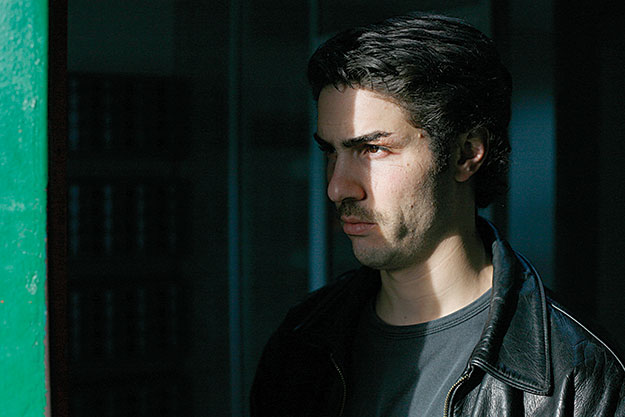

A Prophet

Parodying a scene that has become a standard hook for Hollywood melodrama, von Trier takes a shot at conventional movie manipulation, while defiantly crossing the same line himself. Since the accidental death of a child is the worst thing a parent can experience, we feel squeamish about seeing it exploited—for any purpose, except maybe to get on Oprah. So far so good, but then von Trier goes Bergman-esque. The couple retreat to “Eden,” their shack in the cold, misty woods (Anthony Dod Mantle’s digital cinematography has never been more lyrical, justifying the movie’s closing dedication to Andrei Tarkovsky, which had the audience howling with laughter). The husband, a megalomaniac psychotherapist, takes it upon himself to treat his grief-maddened wife. From Bergman to Buñuel: the wife acts out by literalizing, in surrealist fashion, such metaphors of the war between the sexes as nailing her husband’s thigh to the floor with a spike weighted by a grindstone; crushing his balls with a wrench until he ejaculates blood; burying him alive; and, just to spite herself, cutting off her clit. Gainsbourg performs these grisly tasks in tight close-up and with sufficient intensity to win her the Best Actress award. Art horror yes, but I prefer, crude as it is, I Spit on Your Grave. Several of my colleagues compared Michael Haneke’s circumspect but similarly heavy-handed Palme d’Or winner, The White Ribbon, to Village of the Damned.

Even more graphic in its display of organs and orifices was Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void. Like Resnais, Noé is enthralled by the crane-mounted camera, although the range of expression he wrests from its aerial maneuvers is far more limited. A neo-psychedelic trance movie, this visceral voidoid is shot entirely from the subjective point of view of a young man who, within the first 10 minutes, is gunned down in the filthy bathroom of a Tokyo club. Having promised his sister that he would protect her forever, he—or rather his disembodied spirit—hovers around, until he achieves reincarnation in a way that recalls a much-quoted line from Chinatown. Enter the Void is careless and dopey, but visually quite interesting, and I might have cut it more slack if not for the aforementioned fetus, which, although supposedly first-trimester, looks like a very tiny but fully formed infant. I’m sure that Operation Rescue would happily put it in their educational videos.

Not surprisingly, some of the most pleasurable movies were by directors who fully embrace genre. Jacques Audiard’s A Prophet depicts the jailhouse coming-of-age of a French-Arab man (Tahar Rahim) who is strong-armed by a powerful Corsican inmate (Niels Arestrup) into murdering another Muslim. The Corsican takes him under his wing and teaches him about the workings of power. The young man bides his time, educates himself, consolidates his own base, turns the tables on his mentor, and leaves prison ready to claim his piece of the Paris underworld. Like Audiard’s similarly rich thriller, The Beat That My Heart Skipped, A Prophet is elegantly structured, arresting in its detailing of a little-known subculture, filled with fascinating characters, and gripping beginning to end.

Mother

Two Korean movies, Bong Joon-ho’s Mother and Park Chan-wook’s Thirst, give their lead actresses the respective roles of a lifetime. As the mother of the title, Kim Hye-ja desperately tries to prove that her spoiled, slightly retarded teenage son is innocent of the murder of a young girl. An amalgam of Bong’s small-town detective movie, Memories of Murder, and his rollicking, whip-smart horror film The Host, Mother taps into the reptilian-brained monster lurking within a slight, nondescript middle-aged homemaker. In Thirst, Kim Ok-vin, a former beauty queen with very little acting experience, uses her angelic face to advantage as a sullen Cinderella turned lascivious bloodsucker who wreaks havoc on the family that has abused her when she gets a dose of “bad blood” from a vampire priest. Stealing the film from Song Kang-ho, one of Korea’s biggest stars, Kim owns the screen, so excited is her character by her ravenous hunger and erotic power. Hers was the most thrilling performance in Cannes and probably of the year.

Difficult to categorize because it is deliberately artless and of no discernible genre, Brillante Mendoza’s Kinatay (which translates as “slaughter”) depicts, in 45 more or less real-time minutes, the kidnapping, torture, gang-rape, murder, and disarticulation of a Manila prostitute. The hideous sequence of events is shown entirely through the eyes of a sweet-faced police trainee who, newly married and needing extra cash, signs on for what he thought would be a routine beating. Fortunately for us, he has a partially obstructed view of the action, which takes place in the back of an SUV and then in the dimly lit locker room of an abattoir. But once implicated, he’s afraid to either leave or object. I didn’t leave either, although I was on the verge of doing so many times. Kinatay is serious political filmmaking, which asks that we consider issues of complicity, exploitation, and the morality and the usefulness of bearing witness through photographic images, whether fictional or documentary, to the most extreme crimes against women that are taking place all over the world every day.

There was no way, within the context of such brutality, that Jane Campion’s delicate and restrained Bright Star, a biopic about Fanny Brawne and her romance with John Keats, could get a fair viewing. Campion, whose In the Cut is one of the great art horror films, adopts a diametrically opposite strategy here, brilliantly envisioning the early 19th-century era of the romantic poets as still tethered to the social codes of the previous century. Passion erupts only in the written word; John and Fanny yearn for each other but behave as chastely as in a Jane Austen novel. And in fact, Austen and Keats, who both died young, were almost contemporaries. Besides Wild Grass, there is no other film from Cannes that I more look forward to seeing again.

I might have had a more pleasurable Cannes had I resisted the lure of the “auteurs” in competition, and spent more time in the various sidebars. A prizewinner in Un Certain Regard, Corneliu Porumboiu’s understated, sharply edited and argued Police, Adjective proves that two decades after the putative end of Communist rule in Romania, the law of the state still trumps personal morality. A triple prizewinner in the Directors’ Fortnight, Xavier Dolan’s I Killed My Mother is a more than promising debut by the 20-year-old French-Canadian filmmaker who also plays the leading role. In a festival where Thanatos triumphed over Eros all too often, the sight of two teenage boys rolling on the floor amid Jackson Pollock–like drip paintings, and becoming tenderly, passionately lost in each other’s bodies, could not have been more welcome.