Uneasy Riders

Although the ideal purpose for festivals is to foster international understanding, cultural awareness, etc., this year at Cannes discussions often seemed like a means of carrying on big power politics by another means. The division of current filmmaking into blocs defined as North America vs. Europe vs. East Asia provided the contours for much of the debate, and as might be expected, the films that didn’t fit into these blocs were left somewhat out in the cold.

That’s why it was encouraging to see two fine features from Iran, a country that once looked as if it was shaping up into a real contender. Since its heyday—probably defined by Abbas Kiarostami’s Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1997—Iranian cinema has become increasingly repetitive, returning again and again to formulaic plots involving children, Afghan refugees or both. The filmmakers, of course, haven’t had it easy. The reform movement that loomed so promisingly a decade ago has been pretty much stymied by the increasingly entrenched clerical autocracy, and the effects of that have not filtered down into what had become Iran’s best-known cultural export, the cinema.

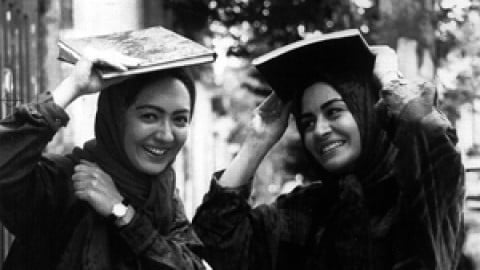

Known for her work as an actress for Dariush Mehrjui (Sara, Pari) and Tahmineh Milani (Two Women, The Hidden Half), Niki Karimi was present in Un Certain Regard with her directorial debut, One Night. A young office worker arrives home one evening only to have her mother ask her to sleep elsewhere that night. From the very first shot one is struck by the power and simplicity of Karimi’s framing. She sets up her camera in a way that makes the living room look like an obstacle course: the two women are separated only by a few feet yet they feel miles apart.

One Night

The young woman leaves. Bus service being at best infrequent, she starts to walk but eventually accepts a ride from a passing motorist. In Iran a woman alone on the streets after dark is by definition suspicious, and so the driver subjects her to a kind of interrogation. The rest of the film is made up of a series of rides with different men. The “car film,” of course, is another staple of Iranian cinema, seen especially in Kiarostami’s work, yet in Karimi’s film it takes on new life. The car serves as a private space in a society that affords its members precious few. The thinly disguised sexual banter of the first driver transmutes into the harrowing confession of the third, as the smooth, gliding passage of the car through the hills of Tehran’s suburbs serves as a counterpoint to the violence of the confession we’re hearing. One Night begins as a story with a well-defined goal and trajectory, but gradually the plot gets overwhelmed by the experience of the journey. In the final shot, the woman and the third driver look out on the lights of Tehran before the dawn—somehow, after all we’ve seen and heard, the city will never be the same.

At the other end of the Croisette in the Directors’ Fortnight, Jazireh Ahani’s Iron Island received its world premiere. A work of extraordinary ambition, the film begins with gliding tracking shots that eventually reveal an enormous, rotting hulk of a ship anchored somewhere in the Persian Gulf. We soon learn that this ship, seemingly so far from shore, is the home for a large and growing group of squatters from every part of Iran and representing just about every walk of life, who have somehow created a community in this most unlikely setting. How or when they got there is never revealed; the only thing that’s certain is that the place is run by the somewhat benevolent dictatorship of Captain Nemat. Well played by veteran actor Ali Nasirian, Nemat is an extraordinary figure, full of fatherly advice and pep but equally willing to resort to abuse if the occasion arises. One is never sure if he’s deluded, or if he’s deluding the community, or if both he and they co-exist in one big delusion. Although their means of living isn’t precisely detailed, it’s clear that the community earns some income by selling off pieces of the ship for scrap; there’s also a suspicion that the ship is gradually sinking. Iron Island is richly suggestive, and everyone who saw it had their own take on what it was trying to express; it’s to Ahani’s credit that he manages to sustain so many possible interpretations right through to the end, when, in an amazing sequence, the film veers off in another direction. Niki Karimi and Jazireh Ahani offer powerful evidence that Iran might once again return to the international cinematic spotlight.