Paterfamilias

At roughly the midway point of every Cannes Film Festival, common themes among the competition films are divined and pointed out, endlessly—in print, on the Net, and in conversation. “Isn’t it amazing?” we exclaim, again and again, at any given hour of the day or night. Curiously, no one ever seems to notice that this is an annual phenomenon. Since we all live in pretty much the same world at the same time, it would be far more unusual if there were no common themes at all and every movie was its own island.

This year it was fathers and children—sons, to be exact. The most obvious link was between two road movies by two old pals: Jim Jarmusch’s small, carefully modulated Grand Prix winner Broken Flowers and Wim Wenders’s loopy Don’t Come Knocking. Two men, washed up (Sam Shepard) and out (Bill Murray, doing some of the best acting of his career), are notified that they (might) have (a) grown child(ren) and venture away from their normal routines (staying at home and counting the hours in Flowers, over-the-hill movie stardom in Knocking) on tentative searches, in both cases yielding dramatically indeterminate results. A nipped and tucked Jessica Lange is the mother, potentially in the Jarmusch, actually in the Wenders.

Wenders’s lurching, wildly discordant film didn’t have many takers—no one came knocking, but a few of us stood on the stoop and waved hello. I myself found it altogether lovable, less for its unfortunate comic stretches (at least it’s funnier than Faraway, So Close) than for its halting, largely unsuccessful yet valiant attempts to reconcile visual beauty with some harsher truths about solitude and aging. It is a film of fits and starts, striking a few modest but welcome grace notes as it lurches from desert cowboy film shoot to Nevada layover (with Eva Marie Saint as Shepard’s mom) to the scene of the crime, beautiful downtown Butte, Montana.

Don’t Come Knocking

Almost everything good about the film has to do with Shepard, who’s never done much for me as an actor—he’s always seemed like he belonged on a coin or a postage stamp rather than in a movie. Here he’s revivified, giving his usual preoccupations as a writer (Old vs. New West, errant fathers and angry sons, off-kilter eccentricities) a funny kick as an actor. Shepard appears to be having a ball as his Howard exchanges clothes with an old cowboy type, wakes up in bed with three manicurists, and, best of all, as he spars with Lange. The two of them obviously know each other inside and out, and they get a lot of mileage out of the old “Honey I’m back”/“Eat shit and die” routine. Wenders’s unfaltering feel for eye-filling events in color and light offers another, more minor pleasure—he makes almost too much of the riot of color inside a casino, or the Hopper/Kerouac potential of Butte. On the other hand, we also get Sarah Polley talking to an urn, and an unrecognizable Fairuza Balk doing a seductive dance on a mattress that’s been chucked out the window by poor Gabriel Mann, as the son, giving one of the most unappetizing performances in the festival (he’s merely a runner-up: the prize goes to the ensemble of Kim Ki-duk’s epochally awful The Bow). Nonetheless, when all’s said and done, I have a feeling that we’d all be unhappy if Wenders weren’t around. Despite his misplaced faith in his abilities as a comic artist, his lack of judgment with actors, and his addiction to voluptuous vistas and faded Americana, there’s not a frame of this unhinged, often grating, and finally touching film that doesn’t betray a profound love of cinema.

There’s a similarly fervent yet profoundly different love of movies and moviemaking in the Dardenne Brothers’ Palme d’Or–winning The Child. A world away from Wenders’s ongoing romance with male loneliness in a clean, well-lit frame, the brothers get their charge out of the cinema’s potential for conveying inner experience. The complaints about their new film began the moment the closing credits started to roll: it’s too formulaic, it’s too much like their other films, every film has been a little less good, etc. All this talk of repetition is intriguing. Whenever a modern filmmaker revisits the same territory, whether moral (Goodfellas/Casino) or textural (Rushmore/The Royal Tenenbaums), they get clubbed over the head. Yet when we look back at Hitchcock, Hawks, Ford, Mizoguchi, we celebrate such repetition. Why?

It is indeed true that The Child has less tension than either Rosetta or The Son, but what doesn’t? This time the story is about a young man (La Promesse’s Jérémie Rénier) living on the margins with his girl Sonia (Déborah François) and their new baby, pulling minor heists with his preteen accomplice Steve (Jérémie Segard) and blowing his share on leather jackets and plush rented cars. Bruno understands nothing but the logic of subsistence and suddenly decides to sell his baby on the black market—“We’ll have another one,” he tells the thunderstruck Sonia. Exactly how he learns to extend his vision beyond the here and now is the film’s central concern, explored and realized as always through an ingenious use of dramatic compression in real time (nothing is conveyed through exposition, action is everything), the toughest social reality, a remarkable sensitivity to sound as a dramatic tool, and a restless camera eye that stays locked on people and events in furious motion. Unlike the last two films, where every word and action twists the knot that much tighter, the groundwork for Bruno’s redemption is laid with scenes that give us his lovability as well as his lack of awareness of himself and others. The tension comes later, with one of the most harrowing scenes the brothers have ever shot.

Free Zone

Is the ending an homage to Pickpocket? Maybe, but it’s a logical outcome, and there’s a crucial dramatic difference between the two films: in the Bresson, Michel finds his salvation in Jeanne, whereas Bruno finds his in himself and offers it to Sonia as proof of his humanity. The child has had to grow up quickly. If there is a shortcoming in this movie, it may have to do with casting—a friend of mine thought that Bruno should have been played by a teenager rather than the now-24-year-old Rénier, and he may be right. But the overall conception of The Child, augmented by Rénier’s considerable charm and resourcefulness, renders such possible deficiencies almost beside the point. Many critics shrugged when the Dardennes netted their second Palme d’Or on a compromise vote. Twenty years from now, we’re all going to look back on what will certainly be one of the strongest bodies of work in cinema and wonder why we were so harshly judgmental.

At the opposite end of the cinematic spectrum is Amos Gitai’s Free Zone. But wait a minute: aren’t the Dardennes and Gitai cut from the same cloth? Don’t they both operate from Bazinian reality-driven aesthetics? Without a doubt. The difference has to do with that old, nagging question of talent. The Dardennes are masters of narrative, while Gitai fumbles his way through pretty much every storytelling chore except the words “The End.” The brothers are equally masters of rhythmic emphasis (the length of every shot is always exact), while Gitai has absolutely no sense of film time as it relates to narrative, character, metaphor, anything. I offer as an example the opening shot of Free Zone. We are in what appears to be the back seat of a car, taking a very close look at a young woman who happens to be Natalie Portman (prediction: Free Zone will be her first and last collaboration with Amos Gitai). The Passover song “Had Gadya” is playing. The woman starts crying. She keeps crying. The song rambles on (it’s a good rendition, by the way). After about four minutes, you start to wonder where those tears are coming from (it’s as if Portman were racking her brains for sense memories—“Let’s see, there was the time my dog got run over by a truck, and the time I threw up at the prom, and…”). Then, she opens the window. It rains in on her for a couple of minutes, as the tears keep flowing and the song keeps playing. She rolls the window back up. More crying (at this point, she’s probably crying because she’s stuck in a Gitai movie). Finally, the song comes to an end, as does the crying, and the woman speaks: “Let’s get out of here.” I’m sure I wasn’t alone in wondering: who’s the poor off-camera schmuck sitting in the front seat of this stationary car who’s had to listen to Natalie Portman crying for 10 minutes? Welcome to Free Zone.

Actually, this is the best Gitai film since Kippur—that’s not saying much, but it’s something. As a film about the entanglements of the personal and the political in a troubled region, it’s easily outclassed by the offhanded eloquence of Rithy Panh’s The Artists of the Burnt Theater, a small but passionately realized documentary-fiction hybrid that went all but unnoticed, not to mention Avi Mograbi’s “personal essay” Avenge But One of My Two Eyes, a despondent look at the Palestinian occupation via a rethinking of core Israeli myths and beliefs. Nonetheless, Gitai’s road trip into Jordan with Portman’s Rebecca and her feisty driver Hanna (Best Actress winner Hana Laszlo, giving a rousing, motor-mouthed performance) is fascinating for its documentary detail, not least within the depressingly vast Free Zone itself, where Hanna is going to conclude a business deal. Once they arrive and meet up with Hanna’s buyer (Satin Rouge’s Hiam Abbass, put to far better use in Hany Abu-Assad’s Paradise Now), the action slowly but surely veers back into the willfully poetic verging on the nonsensical. The trio drives straight into a burning village and observes the ensuing mayhem as if they were in the Museum of Natural History looking at dioramas. Free Zone ends with Portman jumping from the car and running blithely through the world’s toughest checkpoint, in flight from Laszlo and Abbass’s non-stop bickering, destined to go down in history as the worst cinematic representation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Two hens clucking over the same pile of feed would have been more subtle.

Hidden

Perhaps the biggest surprise in competition, the mountainous pretentiousness of Carlos Reygadas’s Battle in Heaven aside, was Michael Haneke’s Hidden. The director’s severity remains intact, but he’s modulated his form of address. Far from the assault of Funny Games, Hidden is a genuine intrigue if not a thriller, which draws us in from the opening shot of an unexceptional house on a nondescript Parisian street. After a length of time, offscreen voices are heard, and we understand that we are looking at a tape, which has been sent to the couple occupying the house under surveillance (the ever-brilliant Daniel Auteuil and Juliette Binoche, unusually sharp, wearing dresses that Joan of Arc might have turned down). Who is making these tapes and why? Haneke takes us step by step from paranoia to panic to a loop back into the husband’s guilt-ridden past to displacement to accusation to subterfuge. The director’s control—of the image (ominously clean, the palette carefully restricted to blues, beiges, grays), point of view (as if the force of guilt itself were the protagonist), and the emotions of his characters (every exchange is precisely graded according to varying levels of openness and evasiveness)—is impressive throughout. The film’s most basic plot question goes unanswered, but Hidden is far from a tease. Its enigma is a productive one, generating considerable dramatic and psychological potency.

The French critics would have none of it. Haneke, who came away from Cannes with a Best Director award, had committed the unpardonable sin of dipping into the collective memory of the Algerian debacle to power his thriller. A moral “error”? A “ridiculous” idea? Such judgments need to be weighed against the worth of what’s onscreen, not vice versa. While it may not be quite the masterpiece that its most fervent admirers (including Abbas Kiarostami) claimed, Hidden is an exceptionally acute film, rivaled only by Cronenberg’s A History of Violence as an inquiry into the mechanisms of human behavior.

It was the Americans who couldn’t fathom the Cronenberg, and neither could the jury. While it’s difficult to say what Kusturica and company made of Hou’s Three Times, the report was that all but one (Benoît Jacquot, who said as much in a series of post-Palmarès interviews) found A History of Violence to be just another overheated Hollywood revenge melodrama with comic elements and Viggo Mortensen in the Steven Seagal role. Thus the two greatest films in competition went unrewarded. Not that it matters much. The mastery and confidence known by Hou and Cronenberg (and only a very few other filmmakers around the world) are their own rewards. Cronenberg’s detractors and qualified admirers tagged Violence as a classical Western redux with a patina of Rockwellish Americana. True enough, but iconography isn’t everything. Every shot, action, and reaction counts, every layer of familiarity leads to a deeper level of unfamiliarity, and this loose adaptation of John Wagner and Vince Locke’s graphic novel finally lands a million miles from Unforgiven and far closer to Dead Ringers or Crash.

A History of Violence

Mortensen is Tom Stall, happily married father of two in an “idyllic” Indiana town, where he runs the local diner and where any parting is apt to end with “See you in church.” When two murderous thugs (Jason Barbeck and Stephen McHattie) take over his diner at closing time, he dispatches them with a few economical moves, and is proclaimed an American hero. Soon he is shadowed by a disfigured mobster (Ed Harris—the most reliable actor in movies?) who insists that the guy behind the counter is not Tom Stall Family Man but Crazy Joey Cusack Out of Philly. On paper, it does indeed look familiar: Eastwood’s Bill Munny, John Wayne’s dying gunslinger in The Shootist, and Shane are obvious forerunners. But here the gun is not forsaken but denied, its existence suppressed, and the resurgence of violence is not a response of last resort but a reflex waiting to happen, again and again and again.

“It was Joey Cusack who did that—not Tom Stall,” confidently proclaims Mortensen’s hero to his chagrined wife (Maria Bello). That Cronenberg doesn’t shy away from the comedy of his protagonist’s “split-personality” predicament is a testament to his supreme confidence. That he never envisions the Tom/Joey dilemma as an all-or-nothing proposition, but instead as infinite gradations of clarity and obscurity, lucidity and madness, is testament to his daring. Best of all, he refuses to play the old art-house game of self-righteously denying the satisfaction of violence. Nor does he shy away from its horror, as two judicious inserts of faces half-blown off and pulverized into a mass of palpitating flesh and bone attest. A history of violence indeed. And just when his hyper-clarity threatens to become oppressive (a fault of the early films), he allows his actors to take their scenes in fresh, surprising directions. Mortensen and Bello must have melded minds with their director. Taken together, their two sex scenes, before and after the reappearance of Joey, are among the finest passages in Cronenberg’s entire body of work. As for the ending, it is as penetrating and disturbing a question mark as the final shot of eXistenZ. This is not the feigned ambiguity of a Trier or a LaBute, but the genuine article—raw, undeniable, as relevant to the characters onscreen as it is to the viewers in their seats.

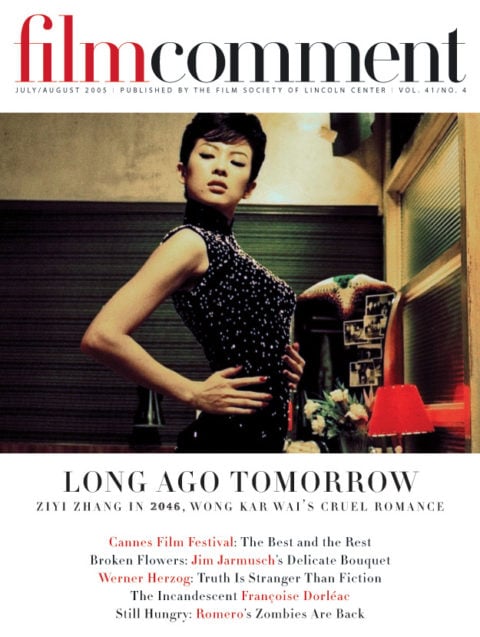

Cannes ended on an unexpected high note for those of us lucky enough to make it to the out-of-competition screening of Princess Raccoon. Seeing the 84-year-old Seijun Suzuki proudly striding into the cramped Salle Buñuel in a tuxedo at four in the afternoon was already exciting enough. That he was accompanied by his star Ziyi Zhang in a white evening gown sent this film critic into a state of delirium before the lights even went down. That the film was exhilarating throughout was the icing on the cake. A digital extravaganza in the vein of Moulin Rouge, Tears of the Black Tiger, and Charlie’s Angels 2: Full Throttle, Princess Raccoon is just as inventive as Suzuki’s Pistol Opera. But where that film was turgidly free-form, this one is held together with a fairy-tale plot, and it soars from one eye-popping setpiece to another. For some, the salsa number was the high point; for others, the rap dance in flip-flops. Me, I was enchanted from start to finish.