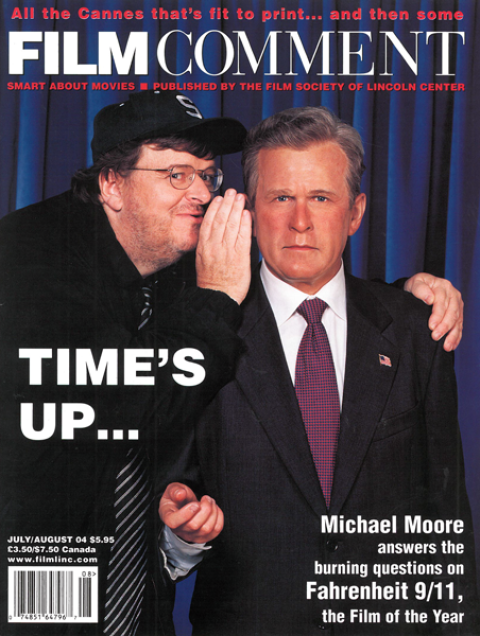

Fahrenheit 9/11

Morning on the Croisette. Fahrenheit 9/11 has taken the Palme d’Or, and the beehive of international film criticism is buzzing with indignation. “C’est scandaleuse!” “Mais c’est pas le cinéma, c’est le télé!” Or, in bluntly accented English, “This is a very stupid Palmarès.”

If the mythical divide of Cannes ’03 was Europe vs. America, Cannes ’04 will go down as the year of cinema vs…. what? Politics? Reality? Michael Moore? Tarantino and his jury spent the better part of their unprecedented post-Palmarès press conference insisting that their choice of Fahrenheit 9/11 was based solely on aesthetic criteria, and that it had absolutely nothing to do with politics. When a meek Italian critic had the audacity to ask whether Moore’s film deserved to stand alongside such previous Palme winners as Apocalypse Now and Pulp Fiction, Tarantino came back at her with his usual charm: “You’re talking about pretty pictures, a’right? I’m talking about pow-er-ful i-ma-ges, a’right?” The bug-eyed hophead president had clearly worked through his talking points with steely prime minister Tilda Swinton and the rest of the jury, a starry-eyed coalition of the willing. Meanwhile, a certain Mr. Weinstein, friend to both judge and victor, was lurking in the shadows like a one-man Halliburton. Which is to say that Cannes ’04 boiled down to nothing more or less than Europe vs. America, Part II.

On the one hand, I sympathize with the point of view of the scandalized, since the politics of Fahrenheit are almost exclusively American. On the other hand, Moore’s film is a far worthier Golden Palm recipient than such forerunners as Pelle the Conqueror, Eternity and a Day, and The Mission. And it’s 100 percent preferable to Walter Salles’s picturesque ode to Youth, Freedom, and the Getting of Wisdom, The Motorcycle Diaries, which everyone expected to win on a compromise vote. Watching Salles’s thin, airy movie is a little like leafing through an expensive book of photographs of South America. “Here’s Buenos Aires… here’s a snowcapped mountain… here’s Machu Picchu… here are some poor people….” It must be said that the monotonously uniform pacing has a lulling effect that’s not unpleasant, and that it’s complemented nicely by Eric Gautier’s handsome images, Gael Garciá Bernal’s perfectly sculpted cheekbones, and Rodrigo de la Serna’s broad, infectiously ingratiating performance. Did I forget to mention that Ché Guevara is supposed to be one of the guys on the motorcycle? Salles might have. The director is so eager to please that his movie could just as easily have been retitled My Most Memorable Spring Break, or Tom and Huck Go to a Leper Colony.

Our Music

Ironically, Swinton invoked Fahrenheit 9/11‘s most noteworthy opponent in one of her press-conference orations, by paying homage to Godard’s out-of-competition Our Music. Little did she know that her hero had been busily complaining to the press that Fahrenheit would only strengthen the resolve of the Republicans, that Moore has a problem distinguishing between words and images, and that he’s only minimally smarter than Bush (upon whom the jury considered bestowing a special citation for Best Comic Performance—”No, we really did, a’right?”). Of course, Godard hadn’t actually seen Fahrenheit 9/11. Different filmmakers, different planets. The fact is that both Moore and Godard have been driven to a greater clarity and concision by the ominous turn of events in the world. Just as Fahrenheit 9/11 is immeasurably superior to Bowling for Columbine, Our Music (Notre musique) is the shining valedictory everyone claimed to see in In Praise of Love, less visually spectacular but far more carefully thought out. Through a process of trial and error that has been ongoing for nearly three decades, Godard has finally found a structure that comfortably accommodates history, myth, and the eternal mystery of the moving image. Where a King Lear, a For Ever Mozart, or even a Nouvelle vague are composed of pieces of variable quality (drearily acted semivaudeville bits, the most eloquent moves from one image to the next alongside the deadliest stretches of dueling literary quotations), Our Music is all of a piece. With help from Dante, the ECM record label, and the city of Sarajevo, Godard allows himself to tell a little story, with a surprisingly low quotient of bewildering displacements, digressions, or ellipses. Which is another way of saying that he has learned to trust his material and allow it to take on a life of its own.

Godard breaks up Our Music into three sections, or “kingdoms”—Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. Whereas Dante envisioned a spiritual progression, Godard sees them as three coexisting states. War may be over in Sarajevo, but it still rages in Palestine/Israel, while Paradise is forever within reach, and Purgatory is always all around us. From the very beginning, it’s obvious that this is going to be a different kind of Godard film. “Hell” is a 10-minute video montage of images of war, both real and fictional, in the manner of Histoire(s) du cinéma. As always, every linkage or drop to black is thrilling, surprising. What feels new is the sense of accumulation. We keep waiting for the montage to end, and it doesn’t. The density and constancy become sobering in and of themselves—it’s not just the fact of war itself but our fascination with it, our eagerness to represent it, that Godard is looking at here. It makes an interesting contrast with Yervant Giannikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi’s Oh Uomo, which was in the Quinzaine. The most monumental of the couple’s handcrafted found-footage films, Oh Uomo feels like an extended proof of Our Music‘s assertion that those who come out of war alive are literally not the same people they were going in. Unlike Marker, who turned these same famous faces of WWI vets into surrealist figures in Remembrance of Things to Come, Giannikian and Ricci Lucchi always linger on them just long enough to sustain the shock of maimed flesh and bone.

Godard’s Purgatory is… a cultural conference in Sarajevo. If that reads like a joke, it doesn’t play that way. “Purgatory” is the most relaxed stretch of cinema Godard has composed in years, and it tunes in to the peculiarly becalmed life of postwar Sarajevo with a welcome delicacy. Godard manages to accommodate everything from didactic exchanges over the differences between victor and vanquished, pleas for withdrawal from Gaza, and readings of discarded books in the ruins of Saravejo’s library, to a pack of Native Americans riding around in a truck, and himself, as himself, giving a lecture on the philosophical implications of shot-countershot. A soon-to-be signature moment: he answers a young woman’s question about whether digital video is the future of cinema with a resigned, teasing silence. In this graceful section of the film, we also get a surprisingly lucid tour of Sarajevo, with a detour to Mostar. The black-and-white Paris of In Praise of Love has a certain grandeur, but it doesn’t get near the freshness and excitement in these quiet images of a destroyed and traumatized city coming back to life. “Paradise” is the same length as “Hell,” and just as potent. We’re by the lake in Rolle, guarded by U.S. sailors. There’s something immediately disarming about the lightness of the camera movement, the trust in natural light, flowing water and green leaves glittering in the sunshine, the face of a martyred young woman stunned by the possibility of true peace in the afterlife. On the face of it, this is as profoundly disenchanted a film as Germany Year 90 Nine-Zero or In Praise of Love. As is the case with all of late Godard, there is a motoring dialectic: the shot-countershot opposition, the idea that victor and vanquished see two different outcomes and two different worlds. Given the essential bleakness of the assertion, how is it that Our Music feels so buoyant and freeing? Godard has come very far from the dark music of Nouvelle vague or the swells of melancholy insight in Histoire(s) du cinéma. He looks at mankind’s worst preoccupation from the most serene vantage point, the better to see it more clearly. Along with Assayas’s Clean, Lucrecia Martel’s The Holy Girl (both severely undervalued), Fahrenheit 9/11, and the reconfigured Big Red One, Our Music was among the most impressive films in Cannes.

Tropical Malady

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Tropical Malady was another sinuous crawl into the ecstasy of the natural world. The second half of the film takes place entirely in a Thai jungle, as a young soldier pursues an elusive beast that assumes the form of his object of desire. Image for image, this hour-long stretch provided the Cannes competition with its most rarefied and ravishing experience. Unsurprisingly for the man who made Blissfully Yours, Apichatpong is almost supernaturally patient (far more so than the Cannes audience) as he tracks the movements of his characters through the luxuriant darkness of the jungle. He slips into the breach between reality and fantasy without skipping a beat—when the love-struck hero puts on a ninja-style facemask, we’re suddenly in some kind of high-minimalist variation on Lang’s “Indian” diptych. There is an image of a tree, lit from within and swaying in the tropical breeze, that is perfection itself, some impossible cross between Magritte, Rousseau, and storybook imagery. As a whole, Tropical Malady is a bit of a letdown—at once conceptually weirder than Apichatpong’s previous films and less exciting in its execution, particularly during the opening scenes in Bangkok. Whereas his first two films uncoil in long, daring passages of real time, Tropical Malady has a more conventional narrative setup that, in the first half at least, feels almost choppy. And while the animal/man/nature idea is cunningly buried within Blissfully Yours, it sits a little uneasily on the surface of this one. All the same, I wouldn’t trade a minute of it for half of the other stuff on display at Cannes.

This year’s festival was bursting with small films that seemed to have slipped through the net, their virtues largely unnoticed, unappreciated, or hastily dismissed as negatives by the frantically judgmental critics. Benoît Jacquot’s À tout de suite, a concentrated, carefully understated look at teenage confusion, is the director’s best film since Pas de scandale, and it provides a perfect illustration of “small” film virtues. Jacquot allows the crazy progression of his narrative—a Parisian girl falls for a small-time hood and winds up destitute and on the run in Athens—to express the emotional turmoil that his oval-faced heroine (Isild Le Besco) keeps to herself. Like any teenager, she’s in far less control than she claims or wants to be. Jacquot’s film, shot quickly in widescreen black-and-white DV and as effortlessly refined as the director himself, is so understated that no one seemed to notice its considerable acuity, which sets it far above the standard French teenage fare with which it was instantly classified. Raymond Depardon’s The 10th District Court: Moments of Trial was another unnoticed highlight—if you were to take a poll of Cannes attendees, it’s 10-to-1 that most either missed it or failed to notice that it was even there. A Parisian civil court doesn’t exactly sound like promising documentary material, but Depardon’s film is a fascinating study of clashing egos and dueling rhetorical styles, reaching its comic high points when the lawyer for a wife-batterer spins a scintillating word-portrait of l’amour fou and then with a grandstanding professional thief who gets a nice, Melvillean compliment from his arresting officer: “He’s good at his job, and I’m good at mine.” Without apparent effort, Depardon manages a thumbnail sketch of contemporary French society, as we watch African immigrants, threadbare artists, and self-righteous academics come face-to-face with the film’s equivalent of Judge Judy—far more bemused, far less moralistic, and betraying an understandable weariness with all the shenanigans she has to witness, day in and day out, from both sides of the law.

Hong Sang-soo’s beautifully titled Woman Is the Future of Man (I’ll say!) won the prize for most invisible film in competition (if you don’t count The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, that is). Hong’s movie is so unassuming that many took it for little more than a riff on his previous work. It unfolds like a minor anecdote: two old friends pay a visit to a former lover (of both men) that extends through the following day and into the night, ending for Hong’s surrogate character in embittered despair. If Cassavetes had been born uptight, pissed off, and South Korean, he might have made this movie. The simple structure, unwinding over roughly 36 hours, unassumingly encompasses a lifetime of disappointment and inescapable male foolishness. It’s quite a rich, absorbing spectacle to watch this supposedly happy family man worm his way into his old lover’s apartment for the night, ask for a blow job so he can get to sleep, run into his students and berate one of them during the obligatory drinking scene, and end up in the most depressing motel room for yet another blow job from a willing student methodically fulfilling a classroom crush. Hong’s mastery—of narrative, of tone—is undeniable, and the acting is utterly flawless. But his new film begs the question: How much does the endless parade of passive women, self-deluding men, drinking sessions, and not so carefully cloaked depression belong to him, and how much is it the property of Korean culture?

Once you’ve seen the film, it’s hard to get the adoring student’s entreaty to her befuddled prof out of your head. With the greatest politeness, struggling to kneel in a miserable room barely big enough to stand up in, this smart, calculating, beautiful young woman utters the soon-to-be immortal line, “May I suck you off, sir?” A suitable slogan for the hard-sell, aggressively sybaritic atmosphere of Cannes.