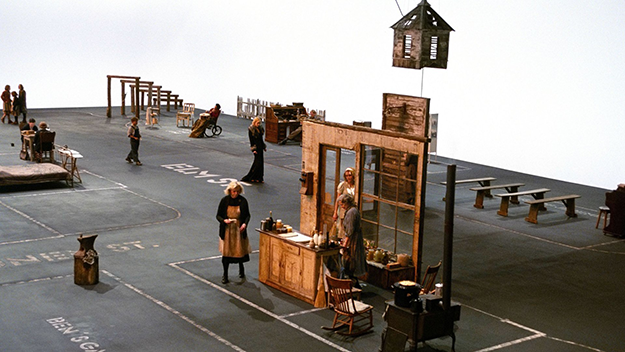

Dogville

Todd McCarthy boldly defended Our Way of Life in his pan of Lars von Trier’s Dogville. His reminder of our beneficent past, at the very moment that we’ve decided to throw out the rule book and plunder the world (not to mention our own economy), is matched generality for generality and cliché for cliché by Trier’s clever, shallow, unedifying movie. Stridency and tone deafness can be found on all sides of the American Question, which provided the 2003 Cannes Film Festival with a depressing coherence.

What is Dogville? Is it a mythical American community run by Tocquevillian consensus, or a genuine microcosm? I would call it a canny construct meant solely for purposes of demonstration, in far-too-perfect sync with the film’s bared-device aesthetic: darkened soundstage, minimal props, unrehearsed acting, frame-as-you-go DV camerawork. And a real massacre at the end. Unless I’m mistaken, this particular representational shock effect was cribbed from Ingmar Bergman’s mid-Eighties staging of Hamlet. But then Dogville is a greatest-hits package of citations and references: Our Town, Ah Wilderness!, The Crucible, Tom Sawyer, Red Harvest, Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, Winnie the Pooh. A fallen woman on the run (Nicole Kidman) is taken in by Dogville‘s motley community of American individualists, led by the local homespun philosopher (Paul Bettany). They overcome their initial reluctance and embrace this saintly, compliant woman · named Grace, of course. And at the halfway mark, right on schedule for a Trier movie, they turn on her, moving in short order from antagonism to chastisement to humiliation to corporal punishment to routine violation. Dogville does hold one genuine surprise, whose impact depends on the film’s only decent performance. Where everyone else clings to their most dependable ticks and tricks, James Caan goes the professional route and makes like he’s in a real movie.

I don’t want to take philistinish pot shots at Dogville. Trier is aiming at a grand cinematic coup de théâtre here, which isn’t problematic on its own terms. But the intellectual confusion at the heart of the film is even greater than the spiritual confusion at the heart of its fictional community. Some of Trier’s admirers, stirred by the ferocity of his point of view, claimed that it was a pointed attack on our great Reaganesque fantasia; other admirers claimed that it was nothing of the sort. If this isn’t America, as the group rendition of “America the Beautiful” at Dogville‘s July 4 picnic (not to mention the final credits) would seem to indicate, then what is it? If it’s a model of fascism in action, then it’s nonsense. If it’s a spiritual inquiry into the inherent difficulties of self-governance, then it’s too enamored of humanity’s worst instincts and unmindful of its best. On the other hand, if this is America, then where is our rampant Christianity? And is the final wipeout meant to parallel our monumentally arrogant foreign policy in general, and our recent incursions into Afghanistan and Iraq in particular? If so, then the movie is even more confused than I think it is (our problem isn’t grandiosity, it’s never-ending, narcissistically tinged paranoia). Trier is a brilliant artist, and the way he tracks his hero’s self-justifications and tortured formulations is impressive. But in the end, Dogville is just as boringly conceptual as Zentropa, another moral mise-en-abime. Gus Van Sant may have tackled the Littleton massacre, but this is the Bowling for Columbine of 2003, just as vague and twice as scornful of humanity.

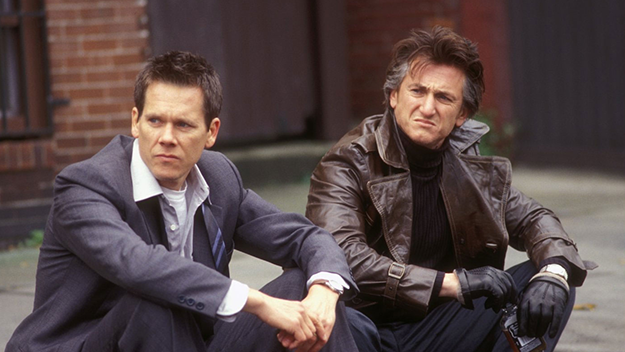

Mystic River

Clint Eastwood’s Mystic River shares a number of concerns with Dogville, but the fact that it’s by a homegrown director who knows the virtues of “classical” storytelling isn’t what makes it the superior movie. Eastwood’s style is as potentially turgid as Trier’s experimental theater mannerisms (ca. 1968) are potentially exciting. But this is by far the more honest, the more complex, and the more passionately engaged of the two films.

Mystic River is, among other things, a terrific Boston movie, getting the East Buckingham neighborhood ambience and even the accents (for the most part) just right. Adapted from Dennis Lehane’s sprawling novel, the action begins in the early Seventies, with three boys playing on a gray day. One of them, Dave, is taken away by two men masquerading as plainclothes cops. He’s locked up and repeatedly violated, until he escapes. Flash forward to the present. The three grown friends are estranged—Dave (Tim Robbins) is a wounded wreck, but he’s also a caring father and husband; Jimmy (Sean Penn) is a small-time, apparently benign convenience store owner and neighborhood patriarch with an ex-con’s wariness; and Sean (Kevin Bacon) is a buttoned-down police detective who rarely visits the old neighborhood. When Jimmy’s teenage daughter is found murdered, suspicion eventually falls on Dave, the weakest link in the human chain.

Like A Perfect World and The Bridges of Madison County, Mystic River has some tonal inconsistencies. And, as was the case with those earlier triumphs, the conception is so sound that the shortcomings feel inconsequential. It may be true that Eastwood is the last of the Hollywood pros, but he has a musical, experimental instinct, more and more pronounced since Unforgiven, that places him in the company of a Pialat rather than a Siegel. You can feel him searching for the right rhythm, the right emotional and moral chord with his actors. When he finally hits that chord, he holds it until it degrades to an uneasy silence. Everyone gets Eastwood’s professionalism, but it’s his daring that’s too often overlooked, the sense of an artist thinking on his feet, going deep into a vexing human question—namely, how is it that people come to destroy one another?

The Fog of War

There are fascinating points of comparison between the Eastwood and the Trier. Both filmmakers edge their way toward grand statements about American mythology. More interestingly, both films are dramas of moral equivocation, pictured by both artists as a natural human practice. Most interestingly of all, both films are capped with odd scenes in which murder is sanctioned as the divine right of kings (corny in the Trier, forceful in the Eastwood). But where Trier imagines that everyone is nice on the outside and rotten on the inside, Eastwood imagines that everyone is a tangle of impulses, drives, and imperatives, good and bad, and that the most responsible among us are the luckiest. Eastwood has orchestrated great things in the past—the death of Charlie Parker in Bird, the rainstorm denouement of Madison County, his own character’s first swig of liquor under a silvery sky in Unforgiven, Costner’s terrifying freakout in A Perfect World—but the final 20 minutes of Mystic River may be the most shattering passage of his entire career.

Mystic River was deemed too soft by many European critics, perhaps because the film’s modesty and careful calibration were miles from the grand rhetorical gestures of Trier, Makhmalbaf, Haneke, et al. A similar fate befell Errol Morris’s Robert McNamara portrait, The Fog of War, the best thing Morris has done in years. Morris allows the architect of destruction himself to approach his record on his own terms, and indulge in hindsight as he sees fit. Slowly but surely, we get a fully rounded portrait of an ambitious man of goodwill, many years past the point when his taste for power has waned, making a game attempt at simultaneously paying for his mistakes and justifying his actions. Morris watches and listens attentively, and lets McNamara hang himself with his own rope. It’s a stunning piece of work, constructed with awe-inspiring intricacy. And when McNamara describes the fire-bombing of Japan, which became the template for the annihilation of Vietnam, borne along by Morris’s precise (and precisely ironic) visual aids, it’s a truly devastating experience.

Visions of violence, destruction, and devastation predominated—unsurprising, to say the least, given the state of the world, but the sheer consistency of it all was exhausting. Samira Makhmalbaf went the allegorical route with her film about present-day Afghanistan, At Five in the Afternoon. Unsurprisingly, Makhmalbaf is still working the same vein as her father, but she has a much lighter touch. In the buoyant first 40 minutes of her third film, she effortlessly sets up the social structure of contemporary Kabul from the point of view of a young woman hungry for education. The immediacy is thrilling, heart-catching. Then, at roughly the two-thirds mark, the plot moves in an illogical direction when the woman, her sister, her starving baby nephew, and her father wander into the desert. Why leave the city with a sick child? Perhaps we’re missing something, but I think Makhmalbaf missed it first, and her movie willfully swerves in a tragic direction that she hasn’t taken enough trouble to set up.

Time of the Wolf

Michael Haneke manufactures his own cautionary but carefully unspecified apocalypse in Time of the Wolf, and then concentrates on the particulars of human existence after all social structures have fallen away—how do people who have been thrown together by circumstance live under the same roof? How do you keep a light source going in pitch darkness when all you have are a lighter and a stack of hay? The logic of survival renders everything else irrelevant—vanity, fairness, personality. The overwhelming dominance of the material world in Haneke’s film is forceful in and of itself, never more than in the scenes staged in the darkest night you’ve ever seen in a movie. It’s almost enough to compensate for the dramatic inertia, a consequence of Haneke’s rigorous consistency—the egos of each character have disappeared along with the social structures, and any hope of a dramatic center along with them. Nonetheless, this is a movie of uncommon, hardworking intelligence, and its central failure—if indeed it is a failure—is an honorable one.

Purple Butterfly, a historical tale of espionage and romantic treachery in early Thirties Shanghai from the overvalued Lou Ye, was an attempted epic of violence and monumental sorrow. Every move in this lush, tastefully appointed movie is filled with promise—the achronological structure, the idea of pushing character into the background and wordless, chaotic setpieces into the foreground, swooning romanticism—but they never develop from vague directorial impulses into full-fledged strategies. Zhang Ziyi may have left a good performance as a Chinese nationalist double agent somewhere on the cutting-room floor, but Lou is such a modish filmmaker that it’s hard to tell. Denys Arcand’s maddening The Barbarian Invasions, a sequel to his slightly more palatable Decline of the American Empire, posits a private apocalypse, the impending death of an all-around great guy. This Hymn to Joy (with wistful nods to Regret and The Passing of Time) is so aggressively anti-elitist that it stoops to a Godard joke, and a dumb one at that. Rémy Girard in the lead manages to keep Arcand’s Neil Simon-ish conceits in working order, but I didn’t believe a minute of it, from the passive-aggressive son who learns to love his dad just in time to say good-bye, to the young, thoughtful junkie who keeps the old man’s veins flowing with smack all the way to the bittersweet end.

Amidst all these visions of doom and mourning, Ross McElwee’s Bright Leaves felt tonic in its simplicity and unadorned lucidity. McElwee remains cheerfully himself, shuttling back and forth through time, poking through his family’s past, examining the circumstances by which his relative, a tobacco producer, was put out of business by Mr. Duke—who got a university, while Mr. McElwee got a nice little park. Thus allowing for a little essay on the beauty of tobacco leaves, their place in the Southern economy, and the rate at which cigarettes are killing the filmmaker’s friends and loved ones. With its small scale, eminently sensible point of view, Bright Leaves felt like the healthiest movie in Cannes.