Review: Call Me by Your Name

In the brief annals of mainstream queer cinema, Call Me by Your Name falls in line with Moonlight in taking a resolutely non-hysterical, non-polemical approach to homoeroticism, treating sexual encounters with a kind of unhurried, tactile sensuality. Society, as enforcer and inhibitor, plays very little part, as both stories take place outside the bounds of middle-class morality—but from different, even opposing ends of the spectrum. Barry Jenkins’s triptych involves a black man’s coming-of-age in Miami, while Luca Guadagnino’s portrait of a teenager’s sexual awakening takes place in a luxuriant corner of Lombardy, but both have demonstrated crossover appeal, Moonlight having garnered multiple awards including last year’s Oscar for Best Picture, and Call Me by Your Name currently carrying ecstatic pre-opening raves from Sundance and Toronto film festivals.

The Italian director who displayed a kind of swashbuckling Euro-chic sensibility in I Am Love (2009) and A Bigger Splash (2015), both featuring a stunningly marmoreal Tilda Swinton as erotic figurehead, moves his latest exploration of Desire with a capital D into a less exalted environment—but only slightly less. We are in the vacation home of the Perlmans (Michael Stuhlbarg and Amira Casar), assimilated Jews and among those casually seigneurial intellectual-bourgeois families of exquisite taste and multiple languages. They enjoy scholarly disputes and culinary delights in an alfresco setting in which the sun itself is a kind of benediction. (The real miracle, it turns out, is one of cinematic artifice: reportedly it rained all summer—the only time the film could be made—and the extraordinary cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom managed to turn dark into light.)

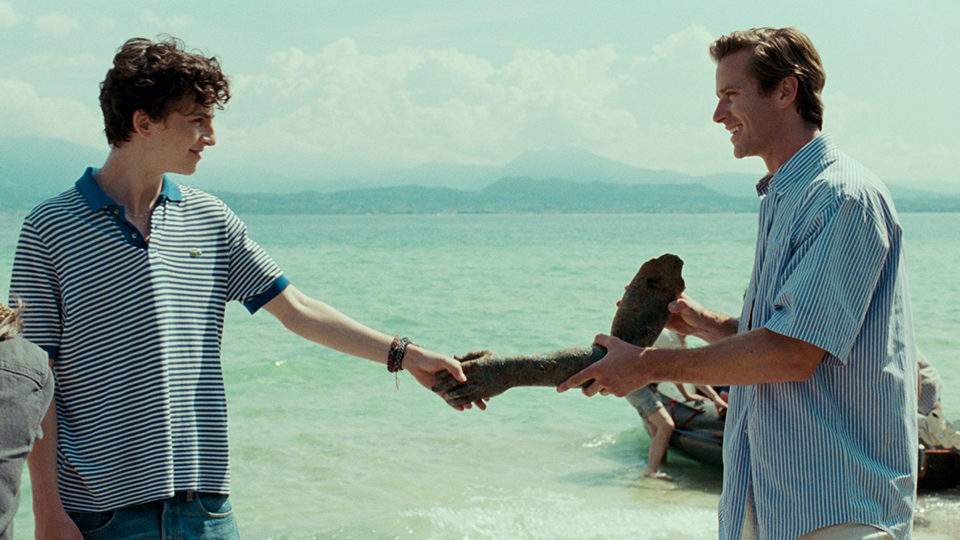

Guadagnino has moved the setting of André Aciman’s 2007 novel from the Italian Riviera to his home base in Northern Italy, but otherwise the screenplay by James Ivory is beautifully faithful. Every year Mr. Perlman, a classicist with archaeological interests, hires an American grad student to help with research and live with the family. Every year the newcomer dispossesses their son, Elio (the remarkable Timothée Chalamet), of his room. But this particular summer, Elio, now 17, will find his way back through a wildly unexpected flowering of lust for the stranger, Oliver (Armie Hammer). The minutely observed vicissitudes of their duet of mutual approach and avoidance, set against a background of picnics, dances, bicycle rides, and swims, form the essence of the drama.

The major difference between page and screen is that where Aciman’s novel unfolded in a heated burst of first-person recollection from the older Elio’s point of view, the movie takes place in the present tense (though it’s set in 1983), and widens the field of vision. Elio is still at the center, bored, flailing, given to fits of despair, but we are no longer cloistered within the sometimes suffocating hothouse of an acutely self-conscious adolescent mind (Does he see me? Does he respond? Dare I speak to him?), second-guessing every move, noting every passing thought and dream fantasy. Other characters—would-be girlfriends who pursue the boys—have their moments, however fleeting, and more importantly, Elio is a gifted pianist. As he teases Oliver with his variations on the classical composers, music forms both a leitmotif and a beckoning vocation. An ingenious score (with original songs) by Sufjan Stevens provides an expressive correlative to the tumult in Elio’s head and loins.

In one sense, Elio is every teenager beset by raging hormones, every adolescent not yet formed, who alternates between longing and terror, flight or fight or fuck, in whom male and female sides still struggle for domination or truce. The struggle is only slightly compounded by same-sex taboo, and the suspense, such as it is, is not whether but when.

The film begins with classical images of male heads and torsos, and abounds with references to Praxiteles and Hellenistic sculpture, establishing and pursuing (sometimes a little too pointedly) the theme of male on male desire. The atmosphere is pagan, the time not just BCE but BCP—Before Cell Phones. Oliver appears rather like a deus ex machina (almost literally: climbing out of a car, blond head rising and rising some more), an Adonis who moves as if by divine right among the French-Italian admirers.

Elio doesn’t know if his attraction is reciprocated; Oliver hesitates, presumably because he must consider the ethics of his position as both guest and older person, and therefore, like Humphrey Bogart, must “think for both of them.” At least I am assuming such reflections are taking place somewhere behind that pleasant but remarkably inscrutable face. Though Oliver wears a Star of David, thus establishing kinship with the Perlmans, Hammer is a more natural signifier of WASP entitlement. He was perfectly cast as the Winklevoss twins in The Social Network: he might as well be a digital double as a real person, as he was when he was rowing with himself at the Henley Royal Regatta. He’s somebody who represents rather than inhabits—an archetype, like his blandly smug philanderer-husband in Nocturnal Animals.

Parker Tyler, that astute chronicler of homosexual themes, gave a mythical dimension to this figure whom he called Homoeros, and saw as transformational in movies like Death in Venice, Billy Budd, The Confessions of Felix Krull, and Teorema. Hammer has none of the ambisexual allure of Terence Stamp or Tilda Swinton. He is a more one-dimensional stud, perhaps closer to the Liv Tyler character in Bertolucci’s Stealing Beauty, an object of directorial lust you have to take on faith. And speaking of Bertolucci, in the movie’s much-talked-about scene between two guys and a peach, Guadagnino also competes with his Italian predecessor for most outrageous coupling of food and sex.

Call Me by Your Name is more invitingly heartfelt and less baroque than the director’s previous films, and skillfully captures both the languor of the summer mood, as time stretches into boredom, and the simultaneous feel of time closing in, of the possibility of missed opportunities, hanging like overripe fruit at the end of a branch. (It’s one of those movies over which fruit metaphors hang irresistibly.)

In the end, the film finds its perfect grace note and even its reason for being not in the final shot of grief-stricken Elio’s anguished face, but in the preceding passage in which his father, in a gesture of exquisite tact and empathy, confers a kind of blessing on him, letting him know he’s aware of the nature of the relationship. Not only does papa not disapprove, he envies the son for leaping where he himself was once tempted, hesitated… and settled for less. In this movie, heterosexual marriage is definitely the consolation prize.

Molly Haskell has written for many publications, including The Village Voice, The New York Times, Ms., Saturday Review, and Vogue. Steven Spielberg: A Life in Films (Yale University Press) and the new edition of her book From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies (University of Chicago Press) are available now.