By Any Means Necessary: Med Hondo

In history and historiography, there were Cheikh Anta Diop and Joseph Ki-Zerbo; in politics, the likes of Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Thomas Sankara, and Malcolm X; in critical studies, Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire; and in cinema, Ousmane Sembène and Djibril Diop Mambety, all battling in their respective ways for a new Africa and a new world. And having passed away in March last year, Mohamed Abid Medoun Hondo, better known as Med Hondo, joins this illustrious pantheon of thinkers, political figures, and artists whose work laid the foundation for the advent of such a world.

Hondo was born in Ain Beni Mathar in Morocco on May 4, 1935. He came from very humble beginnings within the Mauritanian social structure, as a descendant of low-caste freed slaves (haratin). His father’s meager means as a cook for colonial officials made it impossible for him to pay for Hondo’s studies beyond middle school in spite of his precocious brilliance, which was noticed by the French director of his school. The political, class, and caste subjugation he witnessed as a child arguably helped form the bedrock of his longstanding contempt for dominance and his lifelong fight for human dignity. After studying in Morocco in the early ’50s to become a hotel chef, Hondo ended up moving to the metropole in 1956, like many Africans from the French colonies. Landing initially in Marseilles, like his cinematic predecessor Sembène, he found employment as a dockworker, a farmworker, a factory worker, and a cook.

It was also in Marseilles that he began studying the theater, an important influence on his cinema. He continued to act professionally upon moving to Paris, under the guidance of Françoise Rosay, the famous French actress and widow of renowned Franco-Belgian director Jacques Feyder. Hondo studied and performed the European classics, like Molière, Shakespeare, and Racine, but was confronted, like many black actors, with the absence of interesting and complex black characters. So he joined others in creating theater groups like Shango and later Griot-Shango to adapt work by African and Afro-diasporic playwrights and dramatists, including Césaire, Guy Menga, René Depestre, Daniel Boukman, and Kateb Yacine.

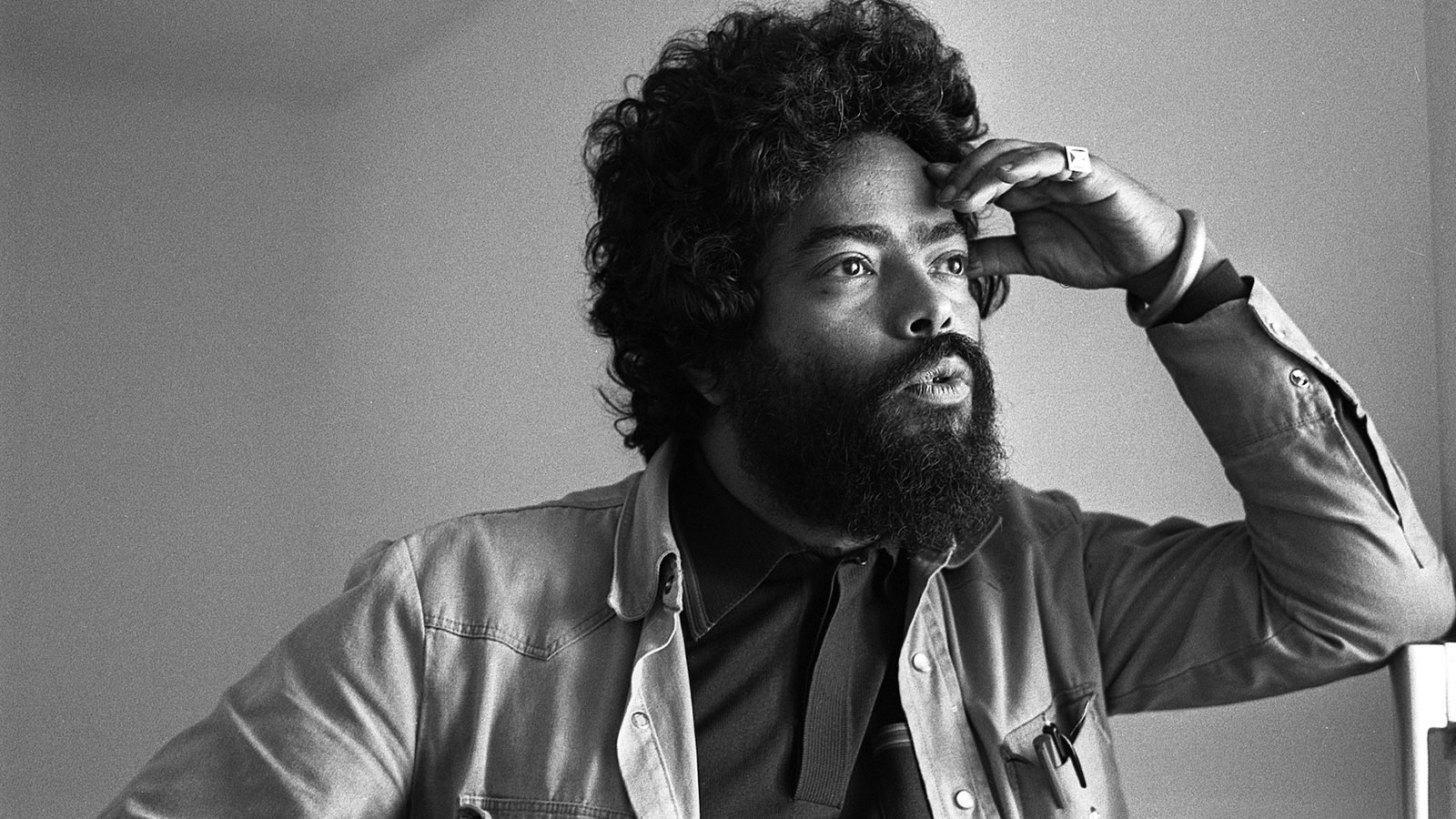

Soleil Ô (Courtesy of Med Hondo/ © Zahra Hondo)

It was less as a director than as an accomplished actor that Hondo earned a living throughout his life. His theater background landed him multiple roles in the cinema, not only on the screen, but also as a voice actor, dubbing in French the voices of many African-American actors in Hollywood films. Hondo nursed the cinephilic childhoods of millions of French and Francophone spectators who saw Danny Glover, Sidney Poitier, Morgan Freeman, Muhammad Ali, and Eddie Murphy on screen, but heard his inimitable and endearing voice. And it was often on the stage that he was noticed and cast by great directors. Jean-Luc Godard (of whom he was no admirer) noticed him in Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman and cast him as an extra in Masculin féminin (1966). Bertrand Tavernier recounts seeing him in Othello and then working as his press attaché on Soleil Ô and Dirty Arabs and Niggers, Your Neighbors. Costa-Gavras, Robert Enrico, and John Huston cast him in their films: respectively, Shock Troops (1967), Zita (1968), and A Walk with Love and Death (1969). It was on these film sets and through long-distance courses that he learned film directing—not through formal schooling.

As a director, Hondo left behind an exquisite filmography of 13 films. Little is known about the first, Balade aux sources (1965)—a half-hour 16mm documentary that, according to him, follows an African man who returns home to the continent and finds himself on a beach reflecting on exile. His second, the only recently located Everywhere, or Maybe Nowhere (1969), already displayed his penchant for experimentation. The film explores a relationship that falls apart as the couple at its center rehearse a play entitled The Martyr King, marking Hondo’s preoccupation with the ultimate modernist problematic of reflexivity—the act of representation and its relationship to the real. Africa and African culture are present in the predominant mbira soundtrack and in the six mask-wearing figures—an African chorus, as it were—who appear at the end, commenting on the death of the protagonist. They perform a sacred walk around him, sit down with scriptures in monk-like positions, dance, and then suddenly vanish, leaving behind their costumes—i.e., leaving us alone with the scene of representation.

Then came the ’70s and ’80s, Hondo’s most prolific and successful decades. He won the Golden Leopard in Locarno for Soleil Ô (1970), the Golden Tanit in Carthage for Dirty Arabs and Niggers, Your Neighbors (1974), and the Golden Yennenga Stallion in Ouagadougou for Sarraounia (1986). In the same period, he directed other important though lesser-known films, including two feature documentaries devoted to the cause of the people of Western Sahara, We’ll Sleep When We Die (1977) and Polisario, a People in Arms (1978). Hondo also produced the documentary La faim du monde (1981), directed by Théo Robichet.

Sarraounia (Courtesy of Med Hondo/ © Zahra Hondo)

It was also in these years that he started encountering censorship, more so than most in his generation faced. He suffered both financial restrictions (never having a bona fide producer or receiving proper distribution) and political censorship, from European and African states alike. Upon the release of Dirty Arabs and Niggers, Your Neighbors in Algeria, African embassies reportedly complained that the film presented their leadership in a bad light and sought to exert pressure on the Algerian government to make the director cut certain scenes. In 1979, during his attendance of the Carthage Film Festival for the screening of West Indies, the Tunisian state reportedly had a police escort and a filmmaker follow him 24 hours a day, as the film had been accused of being anti-Arab because of a scene involving a slave-trading Fulani king. Sarraounia, Hondo’s classic anti-colonial epic, also encountered preventive censorship. Initially intended as a coproduction between Hondo and the State of Niger, the latter withdrew its support at the last minute, allegedly under pressure from the French government. It took the intervention of the late Burkinabe revolutionary president (and noted cinephile) Captain Thomas Sankara for the film to be shot in Burkina Faso. Still, Sarraounia had a very limited release in France, prompting a petition in its defense from major figures in French and African cinema and culture, including Jacques Demy, Costa-Gavras, Tavernier, Sembène, Souleymane Cissé, Paulin Vieyra, Louis Marcorelles, and Ignacio Ramonet.

While still hard at work in the ’90s and 2000s, Hondo was less able to find funding to bring many of his projects to fruition, including one on the leader of the Haitian Revolution, titled Toussaint Louverture, the First of the Blacks. He ended up directing only three more features: Black Light (1994), Watani: A World Without Evil (1998), and his final film, Fatima, the Algerian Woman of Dakar (2004). Together, these films, along with his inaugural shorts and ’70s magnum opuses, constitute a groundbreaking collection of works centered on the migrant condition—the single most dominant theme in his oeuvre. Hondo tackled the question of migration in cinema long before most filmmakers did and was one of the very first to present a genuinely complex historical, political, and economic understanding of the phenomenon. Meaningfully representing the plight of the migrant, however, often led to obstacles in the production, circulation, and exhibition of the films.

Black Light, for example, explores the forced repatriation of Malian migrants, a focus that made for a difficult shoot. The Charles de Gaulle Airport refused to give Hondo authorization to film, and it took the intervention of President François Mitterrand himself for the shoot to proceed. An adaptation of Didier Daeninckx’s novel, Black Light is Hondo’s only (and a rather irreverent) foray into the world of film noir, through which the filmmaker takes on the French state directly. Yves Guyot, an Air France engineer whose colleague was murdered in cold blood by the police, looks for witnesses among expelled Malian immigrants, hoping they will help undo the police’s official account of the killing as a case of legitimate self-defense. Hondo adopts a Citizen Kane–esque structure to show the protagonist visiting various cities of Mali—from Bamako to Timbuktu to Gao—in search of witnesses. The link to Orson Welles is explicit: Hondo pays homage to the director in a nearly three-minute one-take opening sequence reminiscent of Touch of Evil. The classically shot Black Light has some unforgettable moments, such as a flashback to the transfer of the so-called “illegal” migrants in police vans to a hotel room at the CDG Airport. Slow-motion, balletic shots of the immigrants in chains evoke the dehumanizing conditions of the Atlantic slave trade, in a scene aptly accompanied by John Coltrane’s civil rights classic “Alabama.”

Watani: A World Without Evil (Courtesy of Med Hondo/ © Zahra Hondo)

Watani, Hondo’s final film of the ’90s, was deemed too violent for younger audiences in France, its topic being the symbiotic rise of neofascism and anti-immigrant sentiment in the wake of economic turmoil—an ever-resonant theme for our troubled times. The film tracks the parallel stories of French banker Patrick Clément and African garbageman Mamadou Sylla, who both lose their jobs on the same day. While Sylla gets caught up in the endless maze of a merciless French bureaucracy as he seeks employment and housing to be able to stay in the country, Clément soon gives up his job search and falls under the influence of a racist fringe group (at the ironically named “Black and White” bar) that targets and kills migrants by night and dumps their bodies in the Seine. As the migrants are faced with an indifferent and even complicit French state (the film was shot at the height of the implementation of the infamous anti-immigration Charles Pasqua Laws), they organize a collective resistance leading to an explosive denouement. Shot predominantly in black and white, Watani may well be one of Hondo’s most quietly powerful and innovative films. In his first experiment with video, he chooses to de-emphasize speech, instead foregrounding the revelatory potential of the image and the soundtrack via montage. Through crosscutting, he demonstrates that the fate of the migrant and that of the larger French society are inextricably linked. Deploying graffiti paintings, hip-hop music and lyrics, and other vivid markers of youth culture, the film ends in color with close-ups of immigrants looking directly at the camera, collectively folding them into this cinematic work of blues—for Africa, for the migrant, for the human.

For Hondo, along with many first- and second- generation African intellectuals, politicians, and artists, decolonization and independence were not simply a matter of regime change from colonial to postcolonial, but rather a radical geopolitical and avant-gardist project. Through it, the (dis)order of the world could be overturned and a new paradigm initiated, whereby justice, dignity, and liberty would prevail, and racism, imperialism, and capitalism would perish. The cinema had its part to play in the realization of this emancipatory vision by liberating itself from all varieties of dominance, including those of form and tradition.

Indeed, Hondo’s cinema is formally nondogmatic, in that he was open to using any and every available device, genre, and mode, fictional or nonfictional, traditionally filmic or not, as long as it served the film’s aesthetic and political project. His was more of an instrumental than a reverential approach to film form. His best-known film, Soleil Ô—the poignant, semiautobiographical story of an open-minded (i.e., rather naïve) immigrant who arrives in Paris in search of a better life, and has his dreams squashed by endless discrimination—mobilizes a compendium of avant-garde practices. This includes direct address in the opening sequence: a group of African and Afro-Caribbean figures look defiantly at the camera and proclaim their illustrious multi-millennial history and identity (“We had our own civilizations… We forged iron… We had our own legal terminology, our religion, our science…”) against the colonial mantra according to which African history begins with the arrival of the colonizers. It is a scene that brings to mind Langston Hughes’s foundational poem of the Harlem Renaissance, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”: “I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.” Soleil Ô also features Greek chorus–like moments, in which unnamed figures who only appear once in the narrative comment on an action, an idea, a concept, or a mood in the film. In one such insert, a man in a suit with a dog on a leash walks toward the camera and declares: “You are branded by Western civilization. You think white.” Contrary to the convention of one role for one actor, Hondo gives the same actors several roles. The film’s protagonist, an accountant, is portrayed by Robert Liensol, who also plays one of the converts at the beginning of the film, a sociologist in several other parts, and a student in the pedagogic scenes.

Med Hondo on the set of West Indies (Courtesy of Med Hondo/ © Zahra Hondo)

Moreover, through what he referred to as “communicative symbolism,” Hondo succeeds in condensing decades of African history into pithy sequences that invoke both the famous notion that the colonization of Africa involved three Ms—missionaries, the military, and merchants—and the strategy of divide and conquer. In one scene, recent converts confidently march forward, brandishing their crosses, ready for Christian proselytization, only to be transformed into “French-American-English” soldiers intent on destroying the African resistance to colonialism. This transformation is rendered visually by the stop-motion change of costumes and the morphing of missionary crosses into military swords. Elsewhere, Hondo uses puppets to evoke the notion that Africans have lost control over their destinies and are now being moulded in the image of their colonizers.

Dirty Arabs and Niggers, Your Neighbors, which was co-authored with migrant workers, offers a memorable 21-minute opening sequence of cinematic reflexivity that would be an excellent text for any course on ’70s film theory. The film was conceived as an intervention into the struggle of African immigrants in France, as they experienced labor exploitation, housing and employment discrimination, inhumane living conditions, and calls from the right wing to either drown them or reopen the gas chambers for them. Hondo offers one of his boldest cinematic experiments, in the form of a long essay with multiple endings and durations (one version is three hours long), and eight loosely related sequences. The opening features a very long analytical monologue—a move that foregrounds African oral culture as a legitimate cinematic form—by Senegalese actor Bachir Touré, who stands in front of posters of European and American films and performs an archaeology of the African presence in cinema. Implicating the act of filmmaking and the politics of representation, the sequence pays brilliant homage to Marx, played here by the legendary Tunisian critic and founder of the Carthage Film Festival, Tahar Cheriaa. The monologue concludes with an invitation to destroy the oppressive dimension of Euro-American cinema through a literal burning of the posters (an action which Hondo himself is seen directing in the film), anticipating by almost two decades Public Enemy’s classic song, “Burn Hollywood Burn.” The opening of Dirty Arabs and Niggers, Your Neighbors is in effect Hondo’s cine-manifesto, at once announcing and recapitulating the politics and aesthetics of his work.

In West Indies, an explosive demonstration of innovation and virtuosity, Hondo deftly exploits the staging, framing, and montage possibilities of shooting on a reconstructed slave ship to dramatize the migration of Caribbean islanders to France, which he considers a new form of slavery. On this minimalist set, he succeeds in epically evoking, through a beautiful tapestry of colors and costume design, 400 years of history on three continents. West Indies is the exquisite musical satire of an island and a people tossed around by years of colonialism and neocolonialism. We follow the story of the islanders, starting with the election of a pro-French political representative who enacts depopulation policies through vast campaigns of emigration, promising an El Dorado at the end of the journey. But the gap between the promise and the reality is too broad. Life doesn’t improve in the metropole or on the island, and resentment mounts, leading to a full-fledged uprising. The coming-to-consciousness process is intercut with sumptuously staged, composed, and choreographed musical revisitations of the histories of not only enslavement and exploitation, but also the illustrious tradition of radical resistance emblematized by the maroon spirit and the Haitian Revolution. West Indies seamlessly merges intellect and affect.

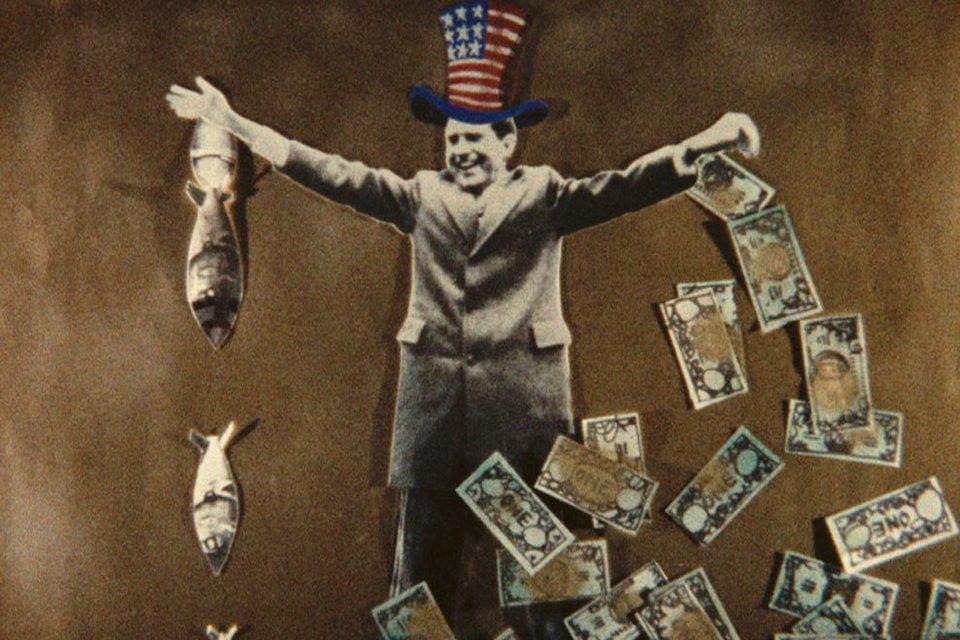

Dirty Arabs and Niggers, Your Neighbors (Courtesy of © Arsenal Institut für Film und Videokunst)

Beyond his own films, Hondo also pursued a grand vision for African cinema as a whole. He often argued that there existed African films but no African cinema, in light of the severe infrastructural and institutional challenges faced by filmmakers across the continent. He consequently devoted a tremendous amount of effort to the creation of structures that would allow African filmmakers to focus primarily on making films. Although he was not a founding member of either the Panafrican Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO) or the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI), the history of these two institutions could not be properly written without accounting for his towering role. Hondo was a formidable presence at FEPACI Congresses and FESPACO colloquia, producing several texts—“What Is Cinema for Us,” “The Cinema of Exile,” and “Of Censorship”—and groundbreaking oral interventions that helped shape its mission. He even created an institution within FEPACI known as the Comité Africain des Cinéastes (CAC), which sought to form an avant-garde group of film directors and professionals who would distribute and exhibit each other’s films in their respective countries. Members of the group included Dikongué-Pipa in Cameroon, Haile Gerima in the United States, Sembène in Senegal, Cheriaa in Tunisia, Benoît Ramampy in Madagascar, and Youssef Chahine in Egypt. It was through the CAC that Hondo was able to release Sembène’s The Camp at Thiaroye (1988) in Paris long after its initial release in Africa.

It is unfortunate that Hondo’s work is not as well-known in Africa as it should be, due to the chronic institutional challenges he fought throughout his life, alongside many colleagues. The work currently being done to preserve and restore his oeuvre is likely to play an important role in the rediscovery of this major figure of African and world cinema. In the diaspora, echoes of his work can already be found in films by Melvin Van Peebles (whom Hondo reportedly hosted during his Paris years in the late ’60s) and Gerima. One can hear a conversation between the hero of Soleil Ô and that of Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971). Likewise Hondo and Gerima may as well be exchanging cine-letters in Soleil Ô and Hour Glass (1971), as well as in West Indies and Sankofa (1993).

Beyond the cinematic, and, indeed, beyond a lifetime of critique, struggle, pain, and exhortation, lay Med Hondo’s pursuit of a radical vision of an Africa that would become aware of her history and reconquer her rightful place in the world—a vanguardist vision of an empowered people and a continent to come, and, through it, of a new world. Begetting them is the titanic task he bequeathed to us.

Aboubakar Sanogo is Associate Professor in Film Studies at Carleton University.