Lola

Early in Jacques Demy’s 1961 debut, Lola, the shiftless, young-ish Roland (Marc Michel) slips into a Gary Cooper movie and emerges transformed. Suddenly resolved to leave the small-town France setting of Nantes (Demy’s birthplace), our hero, a dreamer who claims not to dream, is inspired to learn how to live, one artfully smoked cigarette at a time.

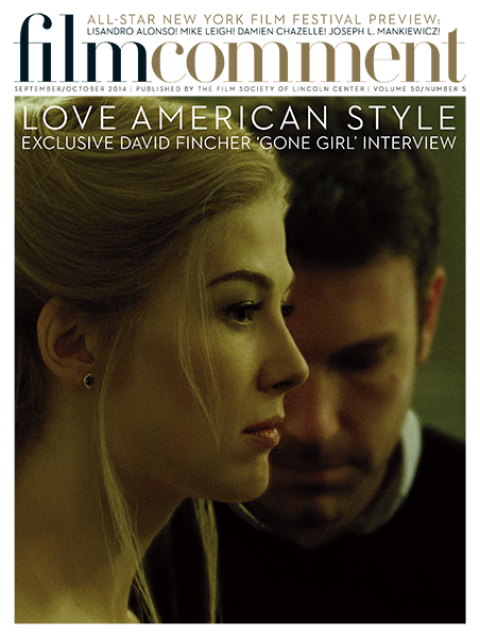

The idea that real life is lived elsewhere, or indeed submits to any scheme, makes a melancholy fool of Roland, who is bound to experience further disillusionment in Nantes the moment he re-encounters his childhood crush, a burlesque dancer who now goes by the name Lola (Anouk Aimée). A cinematic vision of liquid, almost ludicrous femininity (“Think of Marilyn Monroe,” Demy told Aimée, and it’s clear he rarely didn’t), the title character’s impossible allure provides Lola (pictured, above left) with its climactic, deeply cinematic ethos: “There’s a bit of happiness in simply wanting happiness.”

The Young Girls of Rochefort

In the six films that comprise The Essential Jacques Demy, Criterion’s lustrous new box set, the wanting of happiness proves not so simple. A reputation for willful simplicity and wanton sentimentality has set Demy apart from his New Wave contemporaries—a prancing, Technicolor specimen amid a flock of black sheep. This collection emphasizes early work, including Lola, Bay of Angels (63), The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (64), The Young Girls of Rochefort (67), and Donkey Skin (70), but also features the lesser-known 1982 musical melodrama Une chambre en ville, and presents a filmmaker of concentrated depth—a cine-magpie who passes classical style and form through the darker halls of his imagination. In his companion essay on Bay of Angels, in which Jeanne Moreau plays Jackie, a beguiling, boa-clad gambler, Terrence Rafferty observes “Demy’s movies are designed, as Jackie is dressed, to the teeth, and for pretty much the same reason: to put the best possible face on their fatalism.”

Demy’s wife, Agnès Varda, who helped oversee 2K digital restorations of the films (offered in dual-format, looking dazzling on Blu-ray), is a frequent presence in the set’s raft of documentary and archival materials. In one reflection, director Christophe Honoré wonders how Varda squared her husband’s idealization of female types Demy describes as “pretty, pleasant, and simple.” “Adorable idiots,” Honoré calls them. Considering and then dismissing the possibility of a formatively unhappy youthful affair, Varda offers a practiced deflection. Of the source of Demy’s vision, an elusive balance of sincerity and subversion, exuberance and despair, even she can’t be sure.